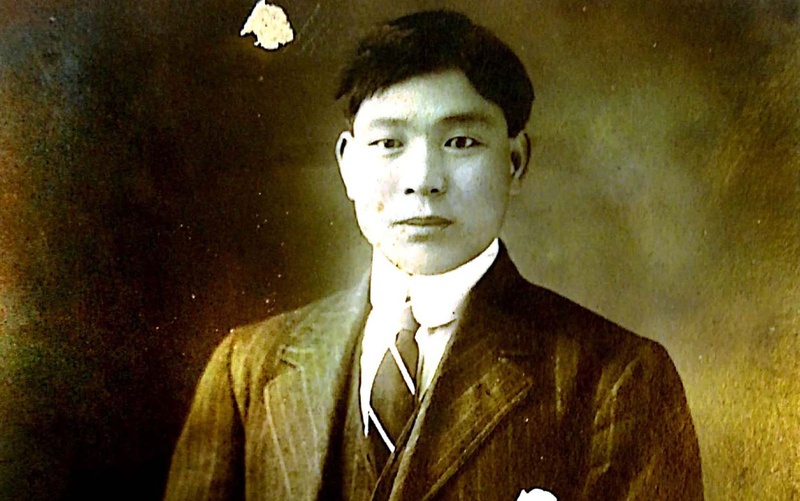

Part one introduced Yoemon’s hometown, Kamai, and how he sailed across the ocean via Hawaii, pretending to be a sailor, and landed in Seattle in 1906. Part two shares a detailed story about how he started his barbershop business three years after his arrival in Seattle.

Barbershop business in Seattle

According to my aunt, Yoemon’s eldest daughter and now aged 102, many of those who moved to America from Kamai back then got their first jobs as dishwashers at restaurants and hotels. Yoemon started the same way. It was a kind of work that required no money, no English, and no skills. Though they had to stand all day from early in the morning until late at night, they were able to make ends meet. Later, Yoemon got into the hog-raising business with a little money he saved. He basically did everything he could to make money.

An opportunity arose for Yoemon one day. He met an individual who offered to help him, and he was able to start a barbershop business in 1909. That person was Chuzaburo Ito from Oshima, an island next to Nagashima where Yoemon was born, in the same Yamaguchi Prefecture. Ito was known as a leader of the Japanese community in Seattle, serving the roles of chairperson at Seattle Nihonjin-kai (Seattle Japanese Committee) as well as Yamaguchi Kenjinkai (prefectural association). Ito was the one who trained Yoemon and taught him management techniques. “A kind man in Oshima helped Yoemon,” said my aunt.

Ito preferentially helped those who were from his home prefecture. As a result, in Seattle, most barbershop owners were from Yamaguchi Prefecture, followed by Fukuoka and Hiroshima. It was a time when people had a strong sense of attachment to their home prefecture and hometown.

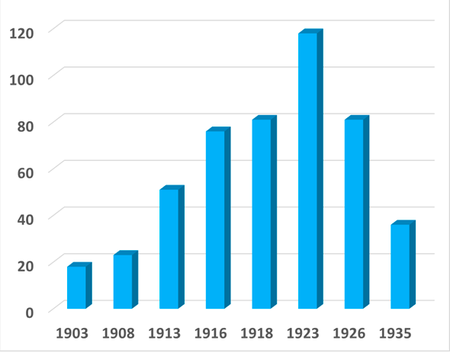

The number of Japanese barbershops in Seattle had started to increase in 1910, and the shops became known as the “snipping barbershops” in the Japanese community. According to some resources, there were 76 Japanese barbershops in Seattle in 1916, and the number had increased to 118 by 1923. In 1916, the number of Japanese barbershops on the West Coast of North America was as follows: 76 shops in Los Angeles, 34 shops in Vancouver, 28 shops in San Francisco, 21 shops in Tacoma, and 15 shops in Portland. Seattle had the same number of shops as Los Angeles, yet considering the total Japanese population, the city had more barbershops per capita than any other place.

Another thing to note here about the barbershop business in Seattle was that their customer base went beyond the Japanese. Most of their customers were middle-class Caucasian European immigrants from Germany, Italy, and other places. There were few barbershops targeting the Japanese. Japanese barbershops were run by couples, and shaving was the wife’s job. The popularity of their business owed a lot to the soft use of their fingers and courteous service done by female workers.

To become a professional barber, it took an average person a minimum of two years, starting as an apprentice, to get a license. They had to take a state barbershop exam. The exam fee was $5; the interpretation fee for foreigners was $3; and a processing fee of 50 cents was also required. A prospective barber first had to take the preliminary exam of the barbershop committee. The state barbershop exam was conducted once a year. Passing this exam granted them a license, and they were allowed to take one apprentice per license.

At the same time, as the number of Japanese immigrants started to increase from around 1900, an anti-Japanese movement surged in Seattle. Especially, people were strongly against the Japanese working in Caucasian society. “Japanese people work too much, and they come in the way of Americans doing their jobs. Besides, they send all the money to their hometowns.” Such was the argument of the anti-Japanese side.

In 1916 Seattle, there were 325 barbershops run by non-Japanese, or Caucasian owners, and from these barbershops began the movement to force out the Japanese barbers. In the midst of such a movement, for the very purpose of peacefully coexisting with Caucasian barbers, the Japanese Barbershop Committee was established in 1907 with Ito as chairperson. The committee had a talk with the Caucasian Barbershop Committee and built a cooperative system in which they set the same service fees and business hours. They always invited executives of the Caucasian Barbershop Committee and tried to maintain the peace. All family members of the committee members attended events such as New Year’s parties and strengthened their bond as they shared fun experiences such as dancing and raffles. As such, under the leadership of Ito’s barbershop committee, many Japanese barbershop owners were able to run their businesses in peace in Seattle.

Opening of Yoemon’s barbershop business

According to the Beikoku seihokubu Nihon iminshi (History of Japanese Immigrants in Northwestern America), Yoemon opened a barbershop in Seattle in 1909 with his cousin Ryunosuke Yoshida from Kamai. The 1913 edition of North American Almanac, published by Hokubei Jiji (The North American Times) notes that this barbershop was located at 163 Washington St, L807. The records of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs report that the shop made $6,000 in 1914 (approximately 12,000 yen in Japanese currency back then or 12 million current Japanese yen).

By the way, Ryunosuke Yoshida is the father of Jim Yoshida, who wrote about his wartime experience, while holding dual citizenship, in his book The Two Worlds of Jim Yoshida, which was published in 1972. In his book, Yoshida wrote about his father, too, and this work, being a work of nonfiction, turned out to be one of the resources from which I was able to get a glimpse of the life of people from Kamai.

Just around the time when Yoemon opened his shop, there were several people in Seattle who came from Kamai. They bonded and helped each other in their work. Yoemon left some notes in his pocket notebook. On the first few pages were the records of money interaction among people from Kamai labeled “tanomoshi.” Tanomoshi is a group of people who put money into a loan that gets distributed on rotation.

I found some addresses on the cover of this notebook, one of which belonged to Ito, proving the connection between Yoemon and Ito.

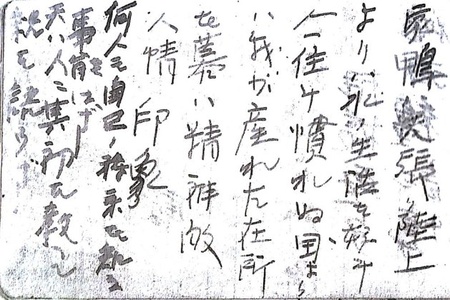

In Yoemon’s pocket notebook, there was a line that described how he felt about his life in Seattle back then.

「家鴨(あひる)は矢張(やは)り陸上より水の生活を好み、人は住み慣れぬ国よりは我が産まれた在所を慕い精神故、人情印象、何人も自己の将来を知る事能はず。天は人に其の初めを教へて続きを語らず」

As ducks prefer the life in water to land, we human beings were all born with the spirit that longs for our hometown rather than the country that we haven’t got used to. With that nature, I cannot stop thinking of Kamai. No one knows their future. A god shows them the beginning and holds the rest.

It shows how hard his life was in America and how much he was thinking about his family in his hometown Kamai. It shows his anxiety about the future, while his life in Seattle was just about to get on track.

I heard about Yoemon’s personality from his brother and sister when I was little. His brother would talk about Yoemon in tears: “My brother worked his butt off in America, was successful, and had his own house built. He was definitely someone to be looked up to, someone who cared about his parents and siblings.” On the other hand, his sister would talk about him with a laugh, “Yoemon could be timid sometimes. I remember him being rather shaken when something bad happened.” Having heard these two opposing descriptions, I thought that Yoemon was sensitive to other people’s feelings, while having a strong desire to be successful.

Later Yoemon would take a “picture bride” from his hometown of Kamai and further expand his barbershop business.

References:

“Shiatoru doho shokugyou shirabe (Seattle Fellow Occupation Research),” in Great Northern Daily News, April 1 to April 5, 1916.

North American Times, Hokubei nenkan (North American Almanac) 1913 Edition.

Takeuchi Kojiro, Beikoku seihokubu nihon iminshi (History of Japanese Immigrants in Northwestern America). Great Northern Daily News, 1929.

*This series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. It is an excerpt from “Studies on Immigrants in Seattle – Thoughts on Yoemon Shinmasu’s Success of Barbershop Business,” the writer’s graduation thesis submitted at the Distance Learning Division at the Nihon University as a history major and has been edited for this publication. The Japanese version was published on July 1, 2019 on the The North American Post.

© 2019 Ikuo Shinmasu