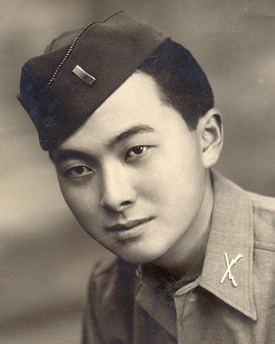

Heart Mountain, Wyoming, 1943. My uncle Kenney Miyake visited us. Uncle Kenney is my mother’s brother. They were born in Portland, Oregon. He wore the uniform of the 442nd Infantry Battalion.

He reached into his travel bag and showed me his Army 45, a monster gun in my little hands. On his uniform was a medal, a Purple Heart because he was wounded in Italy. I wanted to wear a uniform just like my Uncle Kenney. I wanted to be a soldier, but I was only three years old.

After Heart Mountain, during my childhood, boys liked to play war. I was always the enemy. It was my accepted role and I was always shot and taken prisoner or shot dead. I was the Jap enemy. I sort of understood why I was always the enemy, but I was born in America like my parents. We were Americans.

In June, 1950, soldiers from North Korea crossed the 38th Parallel. Soon, the Denver Post would send my father to Korea as a war correspondent. War games changed. There was a new enemy. Unfortunately, I still looked like the enemy.

In 1951, my life changed. My friends and I went to see the movie Go For Broke at the Tower Theatre in Denver. Lieutenant Grayson, played by Van Johnson, was assigned to lead the 442nd Combat Team. With doubts and animosity about a bunch of Japanese Americans, Grayson took command of his new fighting unit and by the end of the movie I was a member of the most decorated American unit in World War II. I could identify with the Go For Broke heroes. The only problem was my white friends all wanted to be Lieutenant Grayson.

Like many Sansei, I take great pride in the 442nd and Uncle Kenney. I visited the Memorial in Los Angeles and found his name. I am proud to be a supporter of the Memorial as a symbol of patriotism, courage, and pride.

In the fall of 2004, my father, a retired journalist with the Denver Post, called and asked me to meet him in Little Rock, Arkansas. He would be speaking at a conference organized by the Japanese American National Museum and funded by the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. Part of the program would be a reunion of the internees from the Rohwer and Jerome camps. The conference also recognized the nine black children, now adults, who in 1957, bravely entered Central High School among the soldiers of the Arkansas National Guard ordered by Governor Orville Faubus to block the integration of the high school and the federal troops ordered by President Eisenhower to protect the children.

Sitting in the audience waiting for the conference program to open, my father said, “I have someone I would like you to meet.” Recognition was immediate. I stood, my mind spinning, and I think I said something like, “It is an honor to meet you, Senator.” I shook his left hand. Nikkei would have recognized Senator Daniel Inouye because we proudly watched on television as one of our own skillfully grilled individuals testifying before the Senate Committee on Watergate.

A most gracious person, we sat and talked for a short time. He told me how he enlisted in the Army with other Japanese Americans from Hawaii as part of the 442nd and how they were trucked across Arkansas to Mississippi for training at Fort Shelby. He described seeing the people in the Jerome camp and knowing he was going to war for his country, their country. He laughingly told me how there was some animosity between the mainland soldiers and the island soldiers. He told me why I am a “kotonk.” Senator Dan was a statesman, a gentleman, and he was awarded the Medal of Honor but he never mentioned it.

Some years after meeting Senator Dan, my father said, “Mike, I would like you to meet Joe Sakato.” I shook hands with a smallish man; neither one of us knowing why we were being introduced. My father said we should get something to eat so we went to a small café, a bit shabby with formica table tops and chrome chairs. A bit of polite chit chat and my father helped out with, “George was in 4-4-2 and received The Medal of Honor.” Stunned, my brain abandoned me. It might as well have been Babe Ruth or Joe Lewis sitting there. A second recipient of the Medal of Honor sat across from me!

George “Joe” Sakato was one of the most humble, shy people I have met. With all the gall I could muster, like a kid asking for an autograph, I apologized, “I know you must have told your story thousands of times, but would you tell me?” This hero was not comfortable telling his story. He looked down and quietly, almost secretively, began. It was fall, 1944, in France and his 442nd unit was pinned down by two German gun emplacements. Caught in an open area, the 442nd was trapped.

The soldier next to Joe peeked up and his helmet and head blew apart. At this point, tears welled up in his eyes and he faltered. Some 50 years had passed and Joe was still deeply affected by seeing his comrade die. Joe’s voice quavered and he went on with his story. He described being mad and running up the hill destroying a machine gun nest and coming around to the back of another to capture it. Joe cried as he talked and had to pause as he told his story.

I later read the citation for the Medal of Honor that includes words like: “…conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of his life…” “…he personally killed five enemy soldiers and captured four…” “Private Sakato made a one-man rush that encouraged his platoon to charge and destroy the enemy strongpoint.” “By continuously ignoring enemy fire, and by his gallant courage and fighting spirit, he turned impending defeat into victory and helped his platoon complete its mission.”

For Japanese Americans, the term “model minority,” is a difficult mantle to wear. It is recognition of the successes and accomplishments of many people who overcame prejudice and discrimination. It is also a point of some derision for selling out our culture, for being the “Quiet American” to assimilate, to be accepted by the majority culture. I am proud and gratified to have met these Japanese American heroes. There are many more Japanese American heroes without medals. We have much to be proud of.

© 2019 Michael Hosokawa