Michelle Yamashiro has been told she has little trouble expressing herself. The vibrant 28-year-old Nikkei is not sure whether her outspokenness comes from her Japanese Peruvian parents, who taught her to “think critically and to have an opinion,” or from her Okinawan grandparents, who wanted her to know and understand their tri-continental family history. Whatever the origin, the former interim director of the youth empowerment group, Kizuna, wants others to share her proud passion for learning about and sharing family history and culture—regardless of how diverse and turbulent the past might be.

Hers is a complex family history that’s not easily deciphered—even for Michelle herself who became interested in it while still attending elementary school in Gardena, CA. The genealogy could be elusive not only for its complexity but because some of her relatives were reluctant to share their stories. Fortunately, her parents and her paternal grandfather, the keepers of their long family history, were eager and available to share with her. They also wanted her to know the difficulties their ancestors faced as they made their way from Okinawa to Peru, and finally to the United States.

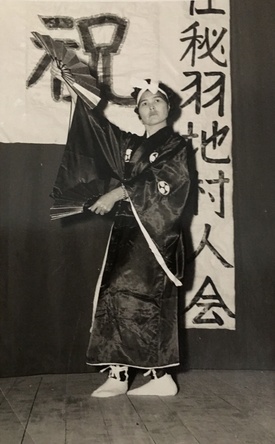

Unlike many her age, Michelle is able to delineate four separate family lines—two on her mother’s side and two on her father’s—each with their own unique immigration history. Perhaps the most celebrated family story comes from her mother’s maternal grandmother, “Obaa” Shizuko Asato, whose husband, Zunshu Asato, was a sumo titleholder from the area of Kumajima in Okinawa.

Apparently, he was enticed by officials in Peru to bring his talents to Lima during the 1920s or 1930s to compete along with other Okinawans known for their sumo prowess. Fortunately, Michelle learned most of this background from her own research into Peru’s history since her great-grandfather died before she was born, and she knew her great-grandmother for only a short time when Michelle was still young. Apparently, when her great-grandmother moved to Peru, Shizuko Asato, like other newly arrived Japanese Peruvians, was baptized Catholic as a means of assimilation, and took on a Catholic name (in her case, Anna Maria).

Her mother’s paternal side of the family, who made their way to Latin America following the war, fought a much tougher battle because by that time Okinawans were not welcome in Peru. During WWII more than 1,500 Japanese Peruvian community leaders and business people, then considered enemy aliens, had been turned over to the U.S. government to be used in a prisoner-of-war hostage exchange with Japan. After the war, they, along with other Japanese immigrants, were not welcomed back. As a result, her widowed great-grandmother Kame Nakamoto, her brother, and her three children were forced to enter by way of Bolivia. Eager to join the larger and more prosperous Okinawan community at that time in Peru, her mother’s brother eventually had to lie about his age in order to enter the country.

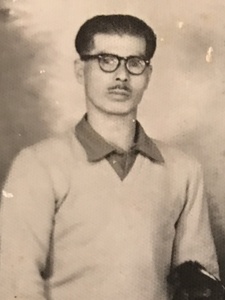

The keeper of her father’s maternal Arakaki and paternal Yamashiro families was her grandfather Soei Arakaki who came to Peru in the early part of the century at a time when they did not face the same Japanese immigration restrictions. Though both sides of her father’s family were from different parts of Okinawa, Michelle learned about much of her father’s history from her grandfather, who lives in Torrance today. According to her grandfather, Michelle was the great-grandchild of a well-respected community leader who narrowly escaped being kidnapped by the U.S. government like other prominent Japanese Peruvians. Those arrested were sent to detention centers in the U.S., to eventually be used in a prisoner exchange with Japan. Educated in mainland Japan, her great-grandfather was literally hidden by community members so that he could stay in Peru where he continued to secretly teach Japanese history and language at night.

Given the varied immigration histories of her family on both sides, with ancestors leaving Okinawa to go to South America as early as the 1900s, details are few regarding how some of her ancestors managed to survive, particularly given the devastating wartime situation in Okinawa. That part of her family history was left untold, and it wasn’t until 2004 when Michelle visited the Okinawa Peace Museum that she learned about the violent suffering of those who remained in Okinawa during the war. She heard stories of women who chose to take their own lives rather than be raped or tortured by enemy soldiers. Particularly moving were the tales of women living and hiding in caves and killing themselves by jumping off a cliff to escape the horror of American soldiers storming the island. “It was a lot to take in,” Yamashiro recalls.

Not aware that she was Okinawan until she was in fifth or sixth grade, at some point she realized that the many stereotypes associated with being from Okinawa were somehow affecting her. Some of those preconceptions were amusing, like Okinawans being always late, or “a bit more chill and relaxed.” Others are deeper, leading many to deny their own heritage for fear of not being “from the mainland.” Once she discovered the many unique characteristics of Okinawans, she developed an appreciation for them. She particularly came to enjoy the “country feeling” she experienced in the culture, music, and arts.

Being Okinawan is not the only culture she relishes as she also finds joy in being Peruvian. “If you were to come to a Yamashiro party,” she smiles, “it would be filled with salsa music and loud laughter, and very, very joyous noises filling the room.” Music is at the center of both Okinawan and Peruvian cultures—whether in the sounds of the sanshin (akin to the Japanese shamisen with similar tones as the American banjo), kachiashi, a song-and-dance that comes at the end of every party, Japanese eisa taiko (typical of Okinawan taiko), or taki music derived from the Inca tradition.

Since leaving her post as interim director of Kizuna, Michelle took time to marry Derek Hirano four months ago, but her appreciation of a diverse and multicultural community keeps her active as she continues her nonprofit work as a volunteer at the Gardena Valley Japanese Cultural Institute (GVJCI) and at the Okinawa Association in preparation for their 110th anniversary. She feels fortunate to be able to provide leadership skills to young people while engaging in identity and cultural understanding for those, like her, who want to show pride in community while at the same time giving back to it. She also emphasizes that it’s important not to give multicultural and multiracial labels to youth, but to “give them the tools so that they can identify themselves and discover what their culture is in hopes of sharing that with other young people around them.”

It’s a skill that she can easily apply to her own journey as she continues to stay community involved, to explore her own family history, and most of all, to speak out.

Video clips from Michelle Yamashiro's interview on August 30, 2018.

© 2019 Sharon Yamato