“During all of those long years of World War II, I took that Evacuation Day very personally. For me, as an eighteen year old, it was an unreasonable action by the U.S. Government that took ‘my Aiko.’”

— Velora Williams Morris

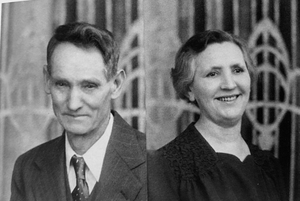

This story of Aiko Ebihara really begins in the friendship forged between two families living in Salem, Oregon, prior to the start of WWII. Aiko’s parents, Maki and Frank, were restaurant owners and full-time cooks at Tokio Sukiyaki, living above the restaurant in a cramped bedroom with three young children. With Aiko on the way, there was simply no room for a newborn baby and an arrangement was made for a family in town, the Williams, to care for her for a few years. The arrangement worked out so well that Velora, the only child of Edward and Alice Williams, would come to embrace Aiko as her own. “I was so proud of Aiko! I wanted to claim her as my little sister,” she wrote. For three years, the Williams raised Aiko in their home, with frequent visits and check-ins with the Tanakas.

But when the war broke out, anti-Japanese sentiment quietly but swiftly permeated the town. The Tanaka’s business took a nosedive, despite the efforts of Frank Tanaka to prove his patriotism: He took out an ad in the local paper pleading, “I have been a resident of Salem for over 27 years. I love my wife, I love my children, I love my home and I love my United States.” The Williams seemed to be the only family that stood by them without question.

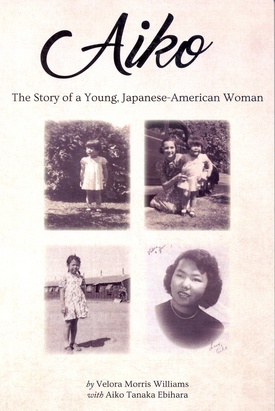

After Velora passed in 2009, Aiko received boxes of letters, photos, and journal entries kept meticulously by her old friend, but with very little organization. Picking up the mantle, Aiko worked with an Oberlin College professor to rework Velora’s precious collection into a book titled Aiko: The Story of a Young, Japanese-American Woman, which is available at the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum.

Aiko’s spotty memories of camp and her early years in Salem were preserved through the eyes of Velora, whose compassion and love for her permeate the writings found in Aiko. From visiting the Tanakas in Tule Lake to remaining lifelong pen pals, it was this kind of unconditional respect — and the Williams’ refusal to succumb to fear-mongering and prejudice — that would define the long-standing friendship between the two families. Mr. Williams even carried a photo of Aiko with him until the day he died.

* * * * *

Could you just give me or start with a little bit of your background of where you were growing up before the war? And what your parents were doing at the time.

I was born in 1935 in Salem, Oregon and my father had a restaurant there called Tokio Sukiyaki. And they were very busy. At the time they had my sister and my brother were living with them upstairs in the restaurant. And then I came along, and soon after my birth, they were looking for someone to take care of me. And I was only like three weeks old, and Mr. and Mrs. Williams volunteered, I guess, or they got a hold of them and they decided they could take me in and take care of me while my mother and dad were busy at the restaurant. And they had a daughter who was eleven years old and her name was Velora. And Velora has always thought of me as a little sister. And always called me her sister.

That’s so sweet.

So it was more like an adopted family. So I grew up with them. And I don’t remember but I assume that my mother would stop by and see me. At least I hope she did.

She probably did!

I’m sure she did, but I don’t remember any of this at all. So Velora really, took care — at that time she was eleven years old and I was three weeks old when I was first brought to her family. So for the next three years, I stayed with them. And so she had written about her experience with me and how she took care of me and she said several interesting things that I never knew that she did with me, and that’s all in the book.

And so your parents, because they were working so hard and they had a lot to do, they just felt it was easier if you lived with this other family?

Right.

So were the Williams good friends with your parents for years before that?

I don’t know. I think a friend of theirs found out that my mother was looking for someone to take care of this baby. And they suggested that Mr. and Mrs. Williams may be a good choice. I don’t know whether they wanted some extra money, maybe? But anyway, so that’s how that came about. [Mrs. Williams was suggested by a mutual friend who knew the Tanakas, and was encouraged to take the job of caring for Aiko].

I see. And how long did you live with them?

Well, I would say at least three years. Three or four years.

And so when your parents said, “We’re going to have everyone live together again,” were they still operating the restaurant? Or did they do something else?

No, they were operating the restaurant at the time until we were interned, until we went to camp. They had to sell the restaurant if they could.

So you were about four or five when you left. But did you stay in touch with this family?

Yeah, I was. We were interned in Tule Lake, so I must have been like three years old. But I have always wrote letters to them while I was in camp.And those appear in the book too. My letters appear in large print like a child would write. And actually I’d never seen, I’d never seen them until she showed them to me. And she said that one of the letters was censored. She only got the envelope and so she can’t imagine what I had written in, you know, what I said about the camp. So, it might have been that the food was terrible or about the soldiers standing guard. And my sister Hazel, who is three years older than I, also wrote letters.

It just shows how paranoid they were, to censor a letter from a child.

Right. I still don’t know what was in that letter. But, you know, then we’ll never know what was in the letter. So we have no idea.

Do you know who your parents sold the restaurant to?

I have no idea. I don’t think they got any — I don’t think they sold it to anybody. I don’t think they received any money for it. We just had to pack up and leave as soon as possible. And then I think we probably left some things with the Williams family, hoping they could keep it for us for when we eventually came out of camp.

Were you living in a Japanese American neighborhood or were you kind of the only family, as far as you remember in Salem?

Well it was, as far as I know, no. It was just American families, Caucasian families.

And what assembly center did you go to before Tule Lake?

We went to Tule Lake and we were there for about a year and then we were transferred to Topaz.

What do you remember about writing to Velora and getting her letters in camp?

I don’t remember anything about that. You know, about receiving the letters or anything. I hardly remember anything about camp.

Did the Williams family come visit your family in Tule Lake?

Yes they did. Velora writes about how they had to go through a lot of security to get into camp. And they had to do a lot in order to get in and visit us.

So the war ends and you’re a little bit older by that point. Did your family go to Ohio immediately? Or what happened after?

Yeah we went to Cleveland, Ohio. Actually, my brother came out first. They did not want to go back to Salem so they went east and went to Cleveland. A lot of interned people were coming out to Cleveland and Chicago on the east side. And since my dad had a restaurant in Salem, he was able to find a job as a cook.

Was it a Japanese restaurant?

No, it was American food. And then they finally found a job at the fraternity house in Cleveland. That was connected with Case [Western Reserve University]. So he was a cook a the fraternity house.

I see, how interesting.

So I actually grew up in a fraternity house [laughs]. On the side they had like an apartment attached to the fraternity house. And the pledges were really nice; they had the pledges build us swing sets in the yard for us. I know all about fraternity life [laughs].

I am curious about your relationship with the Williams family after camp. You obviously moved pretty far away. Did you stay in touch?

It’s amazing we did stay in touch. It was mostly during the holidays. I would send Christmas cards and I would tell her about what I was doing from the time I was in elementary school, junior high. I would tell her everything about my grades, and what subjects I liked, what I was doing, my hobbies. And this went on until I was in high school. And then I would send her my graduation picture. I mean, she kept everything. You can’t believe the pictures that she kept. And most of it is also in the book, too. So I have several of the pictures. But she followed me, I followed and I wrote to her throughout college, marriage and my children. So we kept in touch.

And then when we were in California we decided we would like to visit her. And so I wrote to her that we were going to be visiting and she was so excited because by then it’s been over thirty years that we had actually seen each other.

Right.

And she had always considered me as her little sister. So she said to me that she would cancel all her doctor’s appointments and everything. But you know, I wanted to see her but I didn’t feel that closeness like she did towards me. And so when we went to her house, she was there and I mean she just hugged me and wouldn’t let me go for the longest time. So it was a very nice reunion. And then we also went another time. Whenever we went to California, we’d make a special trip to see her in Medford. And then eventually she was in assisted living, when we last saw her.

When did she pass away?

She passed away in 2009. But the last time that we saw her, she showed me what she was doing. And at that time it was all hand-written that she had made stories about myself. And her handwriting was very small, very hard to read, and she eventually found someone that would do it on the computer. And somewhere in 2010, I received two large boxes. It was all her writings. But nothing was in order, like there were a lot of repetitions of things that she had written. Hand-written, computerized a lot of it was done by chapters the best she could. But it was just a lot of things. I mean she saved everything about my life.

You know, that’s kind of amazing, since you were so young and you don’t have those memories, she almost documented that time of your life for you.

That is true. So it was actually very interesting for me to read about myself. Things that I did with her, you know, and it was just amazing. It was really something else.

Which family member sent it?

That would be Velora’s daughter, Carla. So Carla was evidently supposed to help publish this book with her mother. And it never happened because she passed away. So therefore Carla said she didn’t know how to organize or how to publish a book. Well, I didn’t either. So she sent me the two boxes of all her writings. And so it took us close to over a year that I worked with Lee Drickamer and we organized the book for publication. So it was in November 2017 when we first published 125 books. And then I had to go back again and publish 50 more books.

Velora obviously had such affection towards you and felt very warm towards you and your sister. Did she ever speak about her overall perspective of the camps and how you being uprooted affected her?

Yeah, she did. From what I understand, she was very outspoken about the camp. She was interviewed by a reporter from Medford, Oregon after the 9/11 incident and they wanted to know how she thought about the talk about putting the Muslims into internment camps.

And so he got a hold of her and she said that she couldn’t talk about that, but she said she was very much against the internment camps for the Japanese Americans. So there’s an article that he wrote that was published in the Medford paper. It has a picture of me standing in front of a Tule Lake barrack.

This is such an amazing story of your friendship, between you and her. I mean you are almost like a second family.

That’s right. You know, you can’t imagine, I learned a lot about myself in this book, I really did.

Are you still in touch with her daughter?

No. I did send her the book. And that’s the last time I have been in touch with Carla. And she was very happy to receive the book and she complimented me on how we did a very good job with the book and that her mother would be so proud that it was finally published.

It’s very meaningful for both of your families to have that.

Right. And all of our nephews and nieces and of course my children, too.

Thank you to Discover Nikkei for coordinating this interview.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on April 8, 2019.

© 2019 Emiko Tsuchida