In the face of the tragic events of official confinement and loss that Japanese Americans experienced during World War II, there were numerous non-Japanese who found ways to help Issei and Nisei, or who protested their official treatment. A number of years ago, the Board of Directors of the Military Intelligence Service Association of Northern California approved the founding of the Kansha project to commemorate these individuals, whom one might call the “righteous gentiles” of Japanese America. Writer and activist Shizue Seigel wrote the intriguing book In Good Conscience, which told some of their stories. I have been interested to see that the historian and curator Eric Saul has established a website with a list of such people and their contributions. While I pride myself on my knowledge of Japanese American history, even I learned a lot that I didn’t know from reading Saul’s entries.

To be sure, there will always be quibbles—occupational disease of historians!— about those missing from the list. One candidate for inclusion whom I would consider especially worthy is Florence Crannell Means. In the years surrounding World War II, as part of her larger project of writing children’s books that dramatized the lives of members of minority groups, Means produced works that examined sympathetically the Nikkei. Thanks to the able research efforts of my cousin Corwin Meichtry, I was able to discover important information about this remarkable woman in the Means archives at University of Colorado.

Florence Crannell was born in 1891 in Baldwinsville, New York, the daughter of Phillip Wendell Crannell, a Baptist minister, and Fannie Grout Crannell. She absorbed from both parents a large curiosity and an omnivorous taste for literature. Her father, she later commented, was a man with "no racial consciousness," and his influence on her contributed to her later ambition to promote interracial understanding—as she put it, to teach that "folks are folks." During her childhood she spent summers with her mother’s family in rural Minnesota, which also brought her an appreciation of pioneer life. In 1912 she married Carl [Carleton Bell] Means, a lawyer and businessman who encouraged her to pursue literature. In the next years the couple had one daughter, Eleanor (who would grow up to be the writer Eleanor Hull).

It is not clear when Means began writing for publication. Her first books, a set of fictionalized family stories, recounted the adventures of Janey Grant, a teenager in Wisconsin and Minnesota during the 1870s. For example, in A Candle in the Mist (1931), Means’s first successful book, Janey experiences boredom with her life, until the disappearance of $4000 entrusted to her father changes her outlook. In the following years, Means turned to telling stories of native peoples and racial/religious minorities, with attention drawn to the problems of prejudice they experience. She exposed these primarily though producing novels with young people from those excluded groups—— and with girls and young women as her main characters. For example, Tangled Waters (1936) is the story of Altolie, a Navajo girl of fifteen, who lives in a hogan in Arizona with her mother, stepfather and step-grandmother. Shuttered Windows (1938) features Harriet, an African American teenager from Minneapolis who moves to the Sea Islands of South Carolina to live with her great-grandmother following her mother's death, and is shocked by the poverty there. Whispering Girl (1941) centers on a Hopi Indian girl. The heroine of Teesita of the Valley (1943) is a Mexican American girl living in Denver.

All these books were published by a commercial press, Houghton Mifflin.

At the same time, Means also published a series of works with Friendship Press, the publishing house of the National Council of Churches (then called the Federal Council of Churches). Her first project for them was Children of the Great Spirit (1932), a cowritten nonfiction work described in publicity material as a primary school course for children on American Indians. Her next project, the novel Children of the Promise (1941) deals with Jewish Americans. One of Means’s most-heralded works for Friendship Press was Across the Fruited Plain (1940), a kind of mirror version of John Steinbeck’s epochal novel The Grapes of Wrath. The book tells the poignant story of a once-prosperous mid-Atlantic family, reduced to destitution by the Great Depression, who decide to leave their house behind and travel up and down the East Coast as migrant agricultural laborers.

It was for Friendship Press that Means produced her book Rainbow Bridge (1934), illustrated by China-born American writer/artist Eleanor Lattimore. The book was one of the first sympathetic portraits of Japanese Americans in mainstream fiction. It tells the story of Haruko Miyata, a Japanese girl who comes to live in America with her two brothers, her mother and her father, a brilliant doctor offered a position in an American hospital. The family settles in an unnamed city in Colorado. There Haruko attends American school, attends Christian services, and learns American customs, which the book compares at length with Japanese. In one chapter the family heads out to the country to worship with Japanese sugar beet farmers, and Haruko is shocked to discover that the rural families have such slovenly children and ill-kept houses. In the end, the Miyata family must decide whether to return to Japan or to stay in America.

While its presentation is dated in certain ways, Rainbow Bridge is remarkably progressive for its time in its outlook. Means presents the Miyatas and other Asians in positive terms, and shows respect both for their ancestral cultures and their capacity for good citizenship. While not heavy-handed, the book also does not shy away from a discussion of prejudice. The Miyatas are forced to live in a dingy house in a Japanese enclave of their adopted city—when Haruko passes a nicer street on the way to school, her Nisei friend Gertrude explains that Japanese are not allowed to live there. While the book does not address Japanese exclusion—Dr. Miyata is described as American-born, presumably to explain away how the family could enter the country—there is a discussion of the difficult reception for Asian immigrants at Angel Island. The book also includes a chapter on Tommy Wong, one of the Chinese Americans who befriend the Miyatas, and whose family is threatened with deportation.

Following the outbreak of World War II and the wartime removal of West Coast Japanese Americas, Means would throw herself more heavily into offering support. She befriended a set of Nisei who resettled in Denver, and resolved to dramatize their plight in literary terms. (In the Means papers at University of Colorado are housed a series of questionnaires that Nisei in Denver filled out giving details of their removal and their daily life in the camps, which the author used as background material).

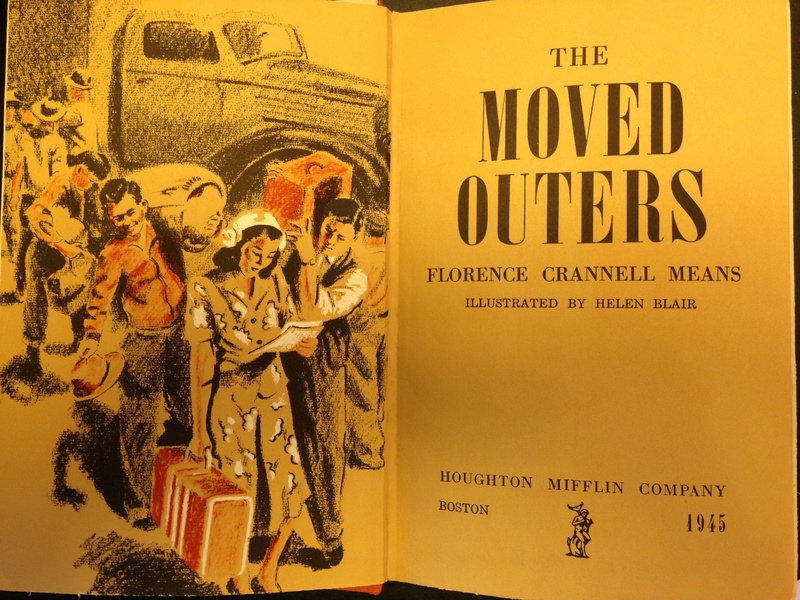

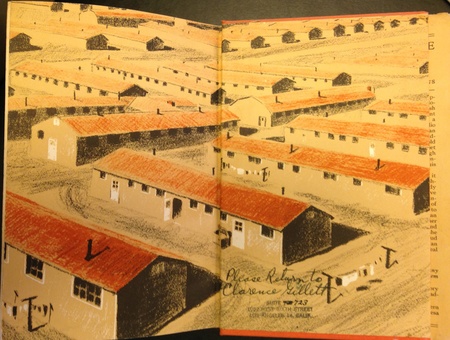

The result was Means’s young adult novel, The Moved-Outers. Published by Houghton Mifflin in February 1945, with illustrations by Vera Bartholomew MacPherson, it was the first full-length published literary work to address wartime confinement. The Moved-Outers centers on a Nisei protagonist, Sumiko (Sue) Ohara, a high school senior from Cordova, California who has two brothers, one of whom is in the Army. After Pearl Harbor, the Ohara family’s life is turned over. Sue’s father is arrested by the FBI, separated from the family and interned by the Justice Department, while Sue, her second brother Kim and their mother are confined, first in the holding center at Santa Anita, and then in more permanent quarters at the Amache camp in Colorado. After confinement, Sue and her mother try to make the best of things while Kim grows sullen and alienated, and gets involved with a “zoot-suit” gang, before he is taken in hand by Jiro Ito, a sympathetic inmate. The book ends in 1943 with Sue’s sister Tomi leaving camp to go off to college in Denver, and the family questioning their future path.

The Moved-Outers was well received by critics. Writing in The New York Times, Ellen Lewis Buell saluted “the timeliness and courage of this book.” Barron Beshoar commented in the Rocky Mountain News that, despite the profusion of official reports and media coverage, “It has remained to Florence Crannell Means to produce the most intelligent and effective piece of writing on the Japanese American evacuation.” The book won the annual children’s book award of the Child Study Association of America for 1945. It remains Means’s best-known work.

Following the publication of The Moved-Outers, Means continued her interest in Japanese Americans. In early 1946, shortly after the end of World War II, she published a story as part of the book Told Under the Stars and Stripes, an anthology of literature by and about minorities. Means’s story centered on Hatsuno “Hattie” Noda, a 12-year old Sansei living in Denver, and her ambivalent feelings toward her great-grandmother, whom she considers “very Japanesey,” but whom she comes to appreciate. The story was reprinted in the San Francisco Nisei newspaper Progressive News, thereby reaching a Japanese American readership.

After the war, Means continued to write multicultural children’s books. In Great Day in the Morning (1946), a sequel of sorts to Shuttered Windows, a black girl from St. Helena Island goes to Tuskegee Institute and then on to nurse’s training. In Assorted Sisters (1947), a white family moves to Colorado to head a settlement house and works with nonwhites. The Rains Will Come (1954) is the story of a Hopi village. Alicia (1953) and Reach for a Star (1957) focus on Mexican Americans. Knock at the Door, Emmy (1956) featured a migrant worker family. Tolliver (1963) recounted the story of a Negro college graduate torn between ambition and the desire to help his people. It Takes all Kinds (1964) is the touching tale of a girl caring for a brother with cerebral palsy. Means meanwhile wrote a pair of nonfiction books, Carvers’ George (1952), a biography of famed African-American chemist George Washington Carver, and Sagebrush Surgeon (1955). She joined with her husband Carl to write The Silver Fleece (1950), on the Spanish in New Mexico.

Carl Means died in 1973. That same year, Florence Crannell Means’s last book, Smith Valley, was published. Meanwhile, as part of the renewed public interest in wartime Japanese American life, The Moved-Outers appeared in a new paperback edition. Failing eyesight curtailed both Means’s traveling and writing in the next years. She died in 1980, shortly before her 90th birthday.

While Florence Crannell Means’s stories and her approach might seem passé to younger, more assertive generations of Asian American readers, at a time of widespread racial hostility toward Japanese Americans and other minorities, her multicultural writings opened many people’s eyes, not just to their plight, but to their humanity.

© 2019 Greg Robinson