The Okinawan immigrant Sentei Yaki introduced tanomoshi to Peru. He helped many Japanese fleeing abuse on the estates by offering them shelter, ensuring their health, and finding them jobs. Furthermore, he was one of the main architects of Nikkei institutions. He was deported to the United States during World War II, but after being released he was able to return to Peru.

Nikumatsu Okada arrived on the Peruvian coast on the first ship that transported Japanese immigrants to Peru in 1899. The man born in Hiroshima arrived as a humble bracero, but thanks to his entrepreneurial spirit, his effort and his vision he managed to become a tenant of six haciendas in the Chancay valley, north of Lima, and become the most powerful man in the area. Okada was also deported to the United States, but unlike Yaki, he was unable to return to Peru and died in Japan, where he traveled after the end of the war.

Yaki and Okada are two of the prominent characters in the history of the Nikkei community whose life and work seeks to disseminate the Museum of Japanese Immigration to Peru “Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka” through a series of exhibitions.

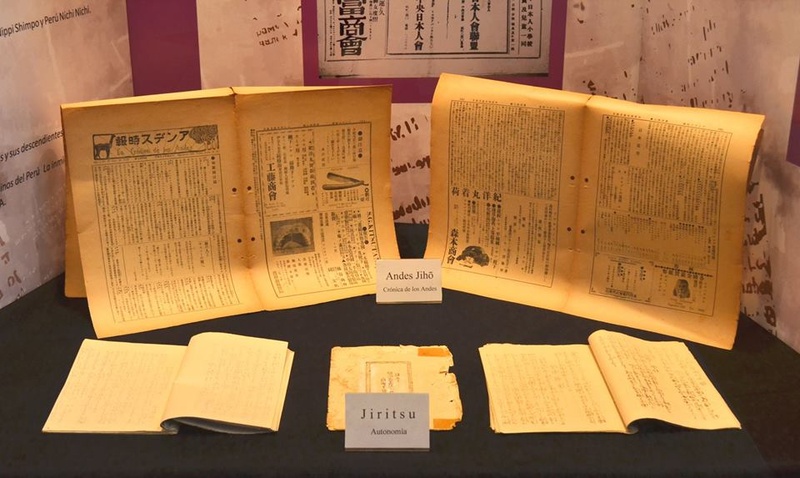

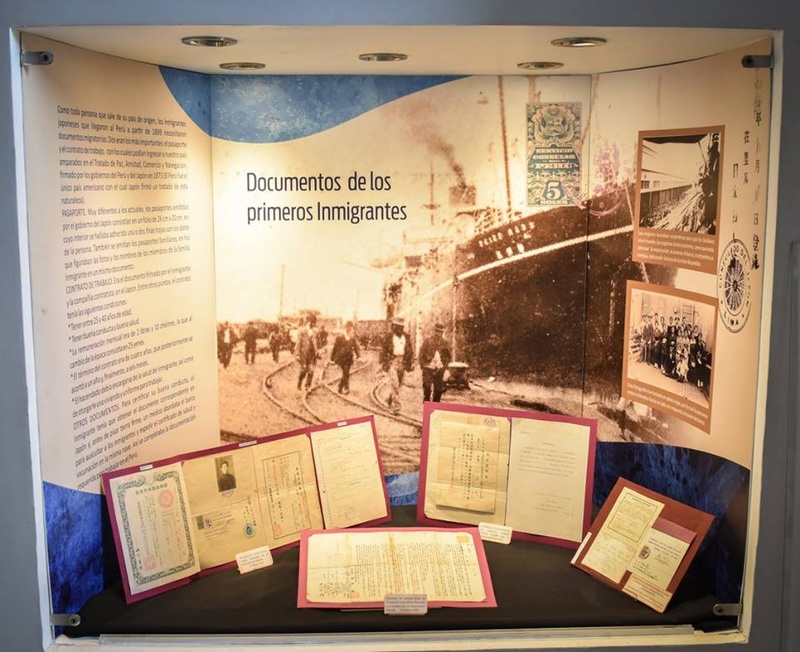

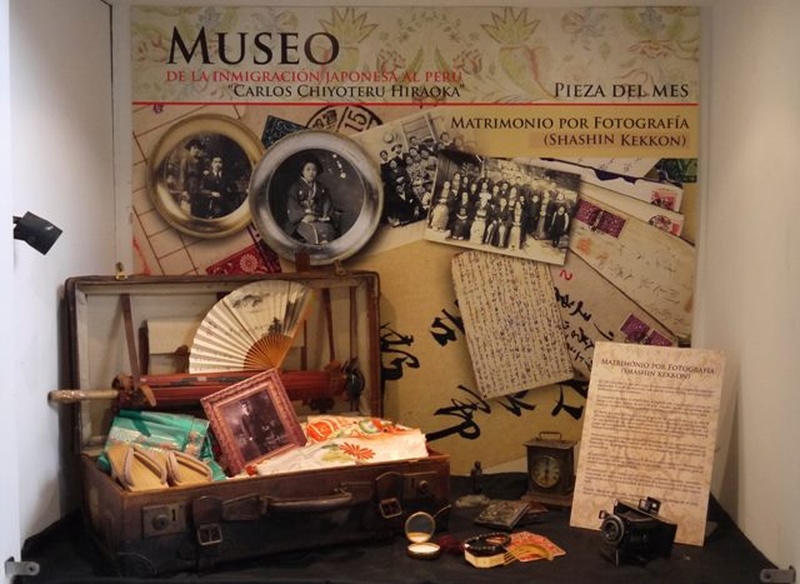

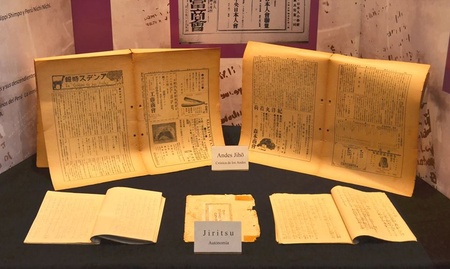

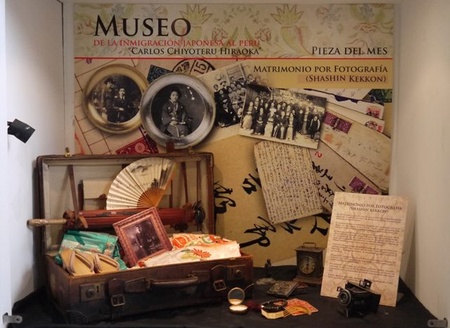

The series started with Sentei Yaki and Nikumatsu Okada is displayed in the temporary exhibition hall. Adjacent to it, a permanent room details the history of Japanese immigration to Peru through texts, photographs and objects that belonged to the Issei, even before the first ship arrived, as it also explains the historical context in Peru and Japan that made mass migration possible.

The museum has been spreading the history of Japanese immigration to Peru for 37 years. It was conceived as a commemorative work for the 80th anniversary of Japanese immigration in 1979 and was inaugurated in 1981.

2018 finds the museum in a stage of change. Its director, Jorge Igei, reveals that there are plans to remodel it, a process that ranges from renewing the information to modifying the distribution of the panels. The last time the museum was remodeled was in 2010.

The objective, he explains, is to facilitate the visitor's journey, to ensure that they do not get lost, that the transition from one space to another is fluid, like someone who intuitively knows what the next step they should take, without the need for signs or indications.

It is also intended that the information reaches the visitor in the most concise way possible. The idea is to make it accessible to everyone. The museum aims at a diverse audience: Nikkei interested in delving into the history of their community as well as scholars from various disciplines, but also people without any relationship with Japanese immigration or the Nikkei.

It is also planned to incorporate infographics and multimedia content to transmit information in a more effective way. For visitors who want more data than what is offered by the panels, monitors will be placed with additional and more detailed information.

The museum regularly receives visits from students from schools from different parts of Lima that have no relationship with the Nikkei community, which shows that interest in the history of Japanese immigration transcends the scope of the community. There are even schools that repeat visits.

The museum director says that visitors without ties to the Nikkei community or its history are struck by how Japanese immigrants managed to put down roots in Peru, a country so different from their own, to blend in with the population and contribute to its progress.

It also receives, for example, Americans who discover, with surprise, that 1,771 Japanese and their Peruvian descendants were deported to the United States during the war.

Or to Japanese who were unaware that in Peru there was a Japanese community that suffered a lot during the war. They find it surprising to learn that in a country so far from Japan and that was not directly involved in World War II, there were people who paid the consequences of a foreign war conflict.

EXPANSION PLANS

Technology is an indispensable instrument in the task of disseminating the history of immigration. Thanks to the support of JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency), the museum has a digital database of Japanese immigrants (names, day of arrival in Peru, place of origin, etc.) that anyone can access.

This database has been and is a valuable tool for Nikkei who want to know more details about the history of their ancestors (whom in many cases they were not able to meet). Japanese descendants come to the museum every week in search of their origins.

The digitization of photos and documents is another of the projects in which the museum is embarking. A task that demands time and resources, but that is advancing little by little so as not to limit the sea of information to physical format and allow people from anywhere in the world to immerse themselves in it.

The museum was born as a means to transmit the history of the Issei and although the original purpose is maintained, its composition has been modified. In the past, it established parallels throughout history between Japanese and Peruvian cultures, especially pre-Columbian, and highlighted the natural riches and tourist destinations of Peru. Today, the museum is focused strictly on the history of Japanese immigration.

Since 2003 it has been named after Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka, a Japanese immigrant who, starting from a small store in a Peruvian province in the 1940s, created one of the most recognized companies in Peru (dedicated to the sale of household appliances). He was mayor of a Peruvian city and one of the main leaders of the Peruvian-Japanese community.

In 2019, 120 years of Japanese immigration to Peru are commemorated and the museum plans to be traveling to leave Lima and take history to the provinces.

GENERATIONAL CONCORD

Jorge Igei highlights the importance of disseminating the history of Japanese immigrants like Yaki and Okada, emphasizing, however, that they do not necessarily have to have been prominent businessmen or leaders. Every effort deserves to be valued, from the Issei who raised and educated his children with his modest restaurant to the one who created a powerful business group.

“Any Japanese person has had an outstanding life. The effort of the Japanese has been like taking off your hat. “The majority have had the attitude of progressing, of getting ahead, of not letting themselves be overwhelmed by all the anti-Japanese sentiment that may have existed at one time,” he says.

An underlining particularity of the Nikkei community, possibly its most notable characteristic, is what it calls “generational harmony.” Unlike other countries where there was massive Japanese immigration during the postwar period, in Peru it stopped during the war. This has made it possible for “generationally the Nikkei community to be homogeneous.” An issei is older than a nisei, a nisei is older than a sansei, and so on. In other countries a Nisei may be older than an Issei, which could lead to intergenerational disputes.

Generational harmony allowed, for example, a peaceful transition in the transfer of power from the Issei to the Nisei in the 1980s, he says. The sessions in the then Central Japanese Society (today the Japanese Peruvian Association, the governing institution of the Nikkei community) went from being held in Japanese to Spanish.

The fact that mass migration stopped during the war means that all Issei who traveled to Peru arrived from pre-war Japan, a very different country from post-war Japan. For this reason, the Nikkei community, even today, maintains customs and even words that no longer have a place in today's Japan, another particular characteristic of the Peruvian Nikkei, points out the museum director.

Another feature to highlight, he continues, is that the harsh times of war (no other Latin American country allowed as many Japanese and Nikkei to be deported to the United States as Peru) strengthened the unity of the community.

Jorge Igei has been part of the museum for five years and says that it has been a period of learning and a lot of effort. “It is an absorbing task, which has allowed me to learn a lot. For me it has been a great satisfaction to be in charge of the museum. Although I do not have museum knowledge, I have been able to do my part so that this can move forward,” he says. Your contribution and learning continue. “Knowledge has no limits,” he concludes.

© 2018 Enrique Higa Sakuda