In recognition of my modest role in the conception and organization of this stellar volume, I received a complimentary copy from Lane Hirabayashi, the lead editor for the robust NCRR editorial team (the others being Richard Katsuda, Kathy Masaoka, Kay Ochi, Suzy Katsuda, and Janice Iwanaga Yen). Along with the book, Hirabayashi attached a short note: “This project exemplifies what Asian American Studies is about for me. From, through, and reflecting grassroots knowledge.” Having had the good fortune to read a substantial portion of his prodigious scholarly output during his 35-year academic career at San Francisco State University, the University of Colorado Boulder, the University of California, Riverside, and UCLA, I was not surprised by Hirabayashi’s message, since virtually all of his writings have been rooted and nurtured in both the concept and the reality of community. Rather than NCRR being the exception that proves this rule, it is instead a quintessential depiction of it.

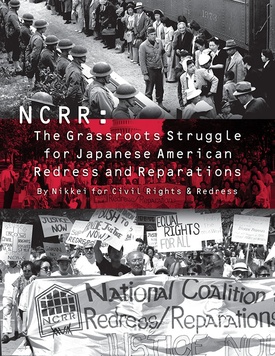

According to the Manzanar blog of Gann Matsuda, whose powerfully evocative photo of the NCRR delegation at the 1989 Day of Protest in Little Tokyo graces the book cover, the book's launch in Little Tokyo in June was “a wonderful event.” I altogether agree with what Matsuda had to say (in so many words) in his posting: that NCRR was and remains a wonderful organization and that NCRR is a wonderful book. My evaluation of both the organization and the book is contingent upon the content, character, and the layout of NCRR. Put a slightly different way, the message I have taken away about the organization derives largely (but not exclusively) from my ardent immersion in the medium per se of their “ethnobiographical” book — “that is, a collective, or a people’s ‘account,’ in their own words, of the life history of the NCRR” (p. 361).

This is a book that enshrines virtually everything noteworthy about NCRR: its freely voluntary and vitally active constituency; its perfervid commitment to community (not alone in terms of Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo and Japanese America, but also of “common” people everywhere who are engaged in a fearless and resolutely perpetual struggle for an expansion of democracy, human rights, civil liberties, and social justice); its enlightened dedication to cultivating a broadly inclusive non-sexist and multi-generational membership both for present and future objectives; and its collaborative decision-making process.

NCRR is comprised of two parts. The first begins by showcasing Glen Kitayama’s 1993 UCLA master’s thesis, “Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress: Grassroots Activism in the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations, Los Angeles Chapter.” This work written from an impassioned participant-observer perspective is comparable in quality to such other exemplary theses as, say, those done in 1970 by Douglas Nelson at the University of Wyoming on the Heart Mountain concentration camp and in 2007 by Kara Miyagishima at the University of Colorado Denver, on Nikkei in 20th-century Colorado. The study by Kitayama, a former NCRR activist, succeeds so well in the volume because it supplies a “valuable context for the emergence of the NCRR and the larger political and social climate of its founding [in 1980] and, at the same time captures the diverse nature of NCRR’s membership … students, educators, truck drivers, IRS workers, retired persons, and housewives” (pp. 12-13). In addition, it documents that many of the NCRR faithful emerged from the 1960s-1970s Asian American Studies Movement and involvement in community-based resistance activity against the redevelopment of Little Tokyo. The study concludes with the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and the transition, two years later, to a new name for NCRR, Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress, and a repurposed organizational agenda.

Part 1 continues with 10 complementary oral history interview excerpts done with noted NCRR activists (all of the book’s editorial team, except Hirabayashi, plus Miya Iwataki, Jim Matsuoka, Bert and Lillian Nakano, and Alan Nishio). These probing and palpable conversational narratives with Nisei and Sansei activists clarify the familial and other experiential reasons leading to their respective affiliation with NCRR and explain how they were able to contribute to its collective development as a democratic/egalitarian organization.

The second part of NCRR, titled “Voices of Transformation: Community Organizers and Activists” covers seven chapters. In addition to a moving overarching prologue by Jim Matsuoka, each chapter includes an introduction. The titles of these chapters are an index to the nature of the always inspiring and often quite emotional personal testimonies that they embrace: “Roots of the NCRR”; “Gathering Voices to Speak for Redress”; “Rallying the Community and Building the Movement”; “The People Go to Washington”; “The Role of Art and the Media”; “The Civil Liberties Act of 1988”; “Creating Linkages in the Quest for Justice”; and “A New Generation of Activists.” Reading and then ruminating upon the 50 variegated selections within these chapters is what best imparted to me the essence of NCRR and its organizational mission and accomplishments.

Rounding out the volume, Hirabayashi provides both a trenchant “conclusion” and a very useful section entitled “For Further Thought and Readings.” The first of these items is distinguished by his articulation of five theses that emerge from NCRR: (1) that NCRR was simultaneously broad-based and multi-generational; (2) that credit for Japanese American redress “should not be ascribed to one key organization, or one key set of individuals”; (3) that the NCRR redress movement “made all the difference” in terms of the passage of the Civil Liberties Act; (4) that beyond the passage of the CLA, NCRR continued struggling “to make sure that justice promised became justice effectuated”; and (5) that with the CLA passage, “Japanese American history continues to be deeply relevant to understanding various dimensions of contemporary struggles for social justice.” The second closing contribution by Hirabayashi focuses on written and filmic works on the Redress Movement that readers might consult in order to provide an enlarged context within which to appraise the achievement of NCRR as conveyed in NCRR.

Among the back matter in this book one finds helpful sections on acronyms, a glossary of terms, an encyclopedic NCRR chronology by Jim Matsuoka of events spanning from 1955-2015, acknowledgements, and a detailed subject index.

This is a book — designed so dynamically by Qris Yamashita and strategically festooned with a remarkable array of photos and other images — that deserves to be read cover to cover. Moreover, it merits being devoured not simply as a historical document, but also as a primer for how to mount and sustain a principled and consequential grassroots movement to counter the oppressive nature of our nation’s current political system.

NCRR: THE GRASSROOTS STRUGGLE FOR JAPANESE AMERICAN REDRESS AND REPARATIONS

By Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress

(Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Press, 2018, 400 pp., $30, paperback)

*This article was originally published in the Nichi Bei Weekly on July 19, 2018.

© 2018 Arthur Hansen / Nichi Bei Weekly