“The most heroic figures in U.S. history, although not always fully appreciated or roundly honored in their lifetime, are those who, like James Matsumoto Omura, were courageous enough to speak and act in an exceedingly moral manner during a time of dire crisis, when it was not popular or even acceptable for them to do so, irrespective of the price that they had to pay.”

—Art Hansen, editor of Nisei Naysayer

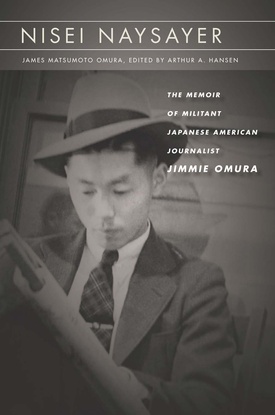

In the long line of historians, journalists, and biographers who have studied the forced incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, there has only recently emerged a trend of celebrating wartime Nikkei resistance. Editor Art Hansen’s book Nisei Naysayer: The Memoir of Militant Japanese American Journalist Jimmie Omura (2018) follows in the path of Michi Weglyn’s Years of Infamy (1976), Roger Daniels’ Prisoners Without Trial (2004), and the documentary Resistance at Tule Lake (2017), in changing the prevailing narrative of quiet Japanese Americans who filed meekly into the incarceration camps during the war. This book is the long-awaited memoir of one of the most prominent Nisei resisters of his time, the journalist Jimmie Omura (1912 - 1994).

Jimmie Omura was born in Washington in 1912, and later moved to Los Angeles. As a young man he chose to pursue a career as a journalist. His star rose quickly in the journalism scene of the early 1930s while editing a variety of Nikkei publications. In these early days, he was not afraid to speak his mind. His publication the New World Daily gained critical acclaim for its elegant writing, but he also incited the ire of Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) supporters by criticizing its leadership. The JACL was already a powerful political influence on the West Coast at the time, and even in this pre-war period its stature was not to be taken lightly.

When Omura continued to speak his mind into the 1940s, criticism of him began to escalate. The war was raging, and the JACL was no longer an organization that sought to promote the people and culture of varying regions within Japan. The JACL now had the responsibility to represent the entire Japanese American population. Because of this, the JACL became a force that had the ear of the national government. However, the JACL was divided in condemning the forced incarceration of Japanese Americans and did not fully use its voice to help prevent this atrocity. This was the wartime JACL under executive secretary Mike Masaoka. At the time, the JACL claimed 25% of Nikkei were disloyal to the United States, and by cooperating with a forced incarceration order Japanese Americans could prove their loyalty and patriotism to the rest of the country. Omura continued to speak out against Masaoka and the JACL despite the criticism.

After Franklin Roosevelt had already signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the military to round up and contain members of any population that it deemed a threat, Omura testified in February of 1942 against forced incarceration. Omura spoke strongly that proof of loyalty and patriotism was completely unnecessary, and even rejected the JACL’s authority to speak for all Japanese Americans. “It is a matter of public record that I have been consistently opposed to the Japanese American Citizens League,” he stated baldly. “Has the Gestapo come to America? Have we not risen in righteous anger at Hitler’s mistreatments of the Jews? Then, is it not incongruous that citizen Americans of Japanese descent should be similarly mistreated and persecuted?” These very public comments led Masaoka to label Omura shortly afterwards as “Public Enemy Number One” at a mass gathering.1

During the war, as a "voluntary" resettler in Denver, Omura continued to blast the forced incarceration and the actions of the JACL. In 1944, in the Rocky Shimpo, he editorially supported Nisei draft resistance at the Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming. This led to him being forced out of his editorship by the U.S. government, aided by the War Relocation Authority and the JACL. It also resulted in Omura being involved in a federal conspiracy trial for undermining the selective service process, a charge for which he was exonerated. In 1947 he was squeezed out of journalism altogether by a combination of personal circumstances and JACL pressure. After that, he disappeared from history for nearly 30 years, banished from public memory at the behest of the postwar JACL leadership. When the 1980s Redress Movement began to dredge up many other dissenting Nikkei voices, including some that had also been silenced by social and political pressures, Omura once again raised his dissenting voice.

In 1983, Art Hansen saw Omura by chance on a bus. He did a double take. During a recent interview with Discover Nikkei, Hansen explained this bizarre but fortunate encounter. “While attending a 1983 conference in Utah on the topic of Japanese American incarceration and redress,” he recounted, “I was a passenger on a shuttle bus from a downtown Salt Lake City hotel when an older man boarded the bus and sat in front of me. I spotted his ID badge that said ’James Omura, Denver, Colorado‘ and abruptly asked ‘Are you possibly Jimmie Omura? I thought you were long dead,’ to which he responded, ’No, I am Jimmie Omura and I am very much alive.’” After that day, Hansen managed to strike up a steady friendship with the most significant voice in wartime Nikkei media resistance. It was also around this time that Omura began writing his memoir, documenting his life before and after the war. It was their friendship, and Hansen’s obvious respect for Omura, that promoted the latter’s family to ask Hansen to edit his memoir.

The book Nisei Naysayer: The Memoir of Militant Japanese American Journalist Jimmie Omura is the product of two decades of work combing through papers Omura left behind. In 2018, Omura’s story is as much needed as it is long-overdue after being kept out of history books for so long. “One of the biggest takeaways for me from learning about Omura [and editing this memoir],” Hansen says, “is how one incredibly principled person can make a significant difference to posterity even if that person was unmercifully persecuted by the powers-that-be of their own racial-ethnic community.” Omura conveys in no uncertain terms in the memoir that “the JACL abdicated its leadership responsibility to the Japanese American community through its compliant, collaborative relationship to the U.S. government. [In doing so,] it imparted to its victims a powerful sense of guilt and shame and a corresponding loss of human dignity.” To counteract this betrayal of its own community, Hansen hopes the modern JACL will "actively participate in valorizing the efforts of past Japanese American dissenters along with their non-Nikkei allies." He feels strongly that not only James Omura, but also stalwart individuals such as Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Wayne Collins, William Hohri, Frank Emi, Ernest Besig, Tex Nakamura, A. L. Wirin, Louis Goodman, Kiyoshi Okamoto, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, Aiko Herzig Yoshinaga, and Yuri Kochiyama, among others, should be nominated to become Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients. Hansen believes that the next move is up to the JACL itself in reckoning with its own history of oppressive policies, ones which Jimmie Omura spent his aborted journalistic career spotlighting and resisting.

Note:

1. James Omura profile on Densho.

* * * * *

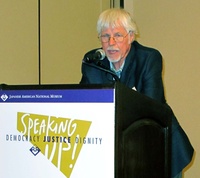

On August 25 at 2 p.m., Art Hansen, editor Nisei Naysayer: The Memoir of Militant Japanese American Journalist Jimmie Omura, will participate in a discussion about the book at the Japanese American National Museum. He will read from the book and lead a discussion about Omura’s life and work. All are welcome.

© 2018 Kimiko Medlock