Fifty years*—half a century ago. We are speaking of another time, another life. We are returning to that era of war, divided loyalties, betrayal, and incarceration. Many of us have already gone, some in fading notoriety, some with trauma and conflicts unresolved.

If the median age of Japanese Americans in 1942 was seventeen, then my contemporaries and I were the average Japanese Americans of the time. We were seniors in high school. In another semester, we would graduate. And soon we would face grave situations and make important decisions.

Excluded from mainstream American society, we were more Japanese than American. We had watched our parents struggle through and survive the Great Depression; our thinking was narrow, our ambitions modest, and we were politically and socially naïve. We separated the politics of nations from ourselves, even though they were inseparable from our parents’ lives: the Alien Land Law, exclusion from citizenship, job discrimination. Although these truths appeared everywhere everyday, most of us believed our history books – America the land of the free, of Horatio Algers, and the melting pot of the world.

War was raging in Europe. Every month there was another scare of war with Japan. The Draft faced our young men ready to graduate. College was an option. One could go to a university, become a doctor or lawyer or an accountant and serve the Japanese community. One could be an engineer and sell fruit in a roadside stand, or an electrician and fix toasters and radios, or a poet or artist and tend a nursery or trim lawns and hedges for wealthy whites. One could work a store or an office or farm a few acres like his father before him and wait to be inducted in the army. It was for men, a time to put childhood behind.

Being a girl was easier. For a long time I looked forward to falling in love, preferably to a dashing Robin Hood type, to a marriage that held no clue to reality – the cooking, cleaning, and budgeting part – to children who didn’t soil diapers, and to a pink stucco house. Maybe.

But it was plenty to look forward to. Didn’t the movies tell us so? Wasn’t that the promise of the American dream? It was far more than our parents had or dreamed of having.

My mother left her native Japan and yearned for it forever after. She spent her productive years on a patch of leased land, moving every two years, seeding, harvesting, eking out a frugal living, watching her children drift away, grow more alien as the years slipped by. My father was trapped in the same pattern. In addition, he tried valiantly to hold on to his self respect, his image as man, provider, and protector.

It was a narrow world we average Japanese Americans were born into, but like setting a microscope on a drop of water, there was teeming life beyond the naked eye.

From an early age I was aware of a vastly different world outside our farm. My father bought a twenty volume set of The Book of Knowledge and I poured over drawings of prehistory, reproductions of famous paintings, and illustrations of classic stories and poems. There were stiff portraits of important people and their important inventions. Among them was Dr. Noguchi who my mother said conquered yellow fever in the tropics. I don’t know if this is true, but I had to accept her word because I couldn’t read, but I never forgot it because I knew then, it was possible for Japanese to be in The Book of Knowledge. I felt proud.

The paintings fascinated me. There were swaggering portraits of a privileged class, of satin, jewels, buckled shoes, grand capes, and sweeping feathers. I was a kid peering through a candy store window.

But it was the black and white reproductions of Corot that moved me the most—the distant landscapes of peasants tending their animals in a glade, the chill of dusk in the air, the quiet sense that life went on before and will go on long after I am gone. It was the power of art to transport, to stir memories transcending experience. Here beyond the painting, the sky turns dark, supper steams over an open fire, and love awaits. I would be a painter when I grew up.

But let us now praise the resilience of youth and the hope that springs eternal and other timeless clichés. We were the America of the melting pot. In spite of the evidence, we did not doubt our country and the principles of democracy we read so much about. Lessons on slavery, greed, and chicanery were yet to come. And suddenly with the attack on Pearl Harbor, we were no longer Americans.

Who can forget what he or she was doing on that day?

I had gone to see Sergeant York at the Oceanside Theatre (we’d moved to Oceanside by then) and I’d spent almost two hours watching an All-American nobody become a hero shooting Germans the way he shot wild turkeys in the Tennessee hills. I came home full of rah-rah. My mother met me in the yard. She whispered, “America is at war with Japan.” Her face was white; my heart sank for her. At the time I didn’t dream of the implications. So on Sunday, December 7, we became the enemy.

We average Japanese Americans of seventeen years were powerless to stop what followed. Many of our fathers and community leaders were whisked away to detention camps and our homes were raided systematically. Some people advocated voluntary evacuation. “Let’s be good citizens and show our loyalty by leaving voluntarily.” Our self-hate and guilt were enormous.

Then with Executive Order 9066, we were forced to cram our lives into two suitcases and leave our homes. There was a small group who urged us to “fight to the last ditch.” They said maybe some of us would die, but the world would then know we accept nothing less than full citizenship rights. The American Way.

But who wants to die? The idea did not take hold and we went on to the camps.

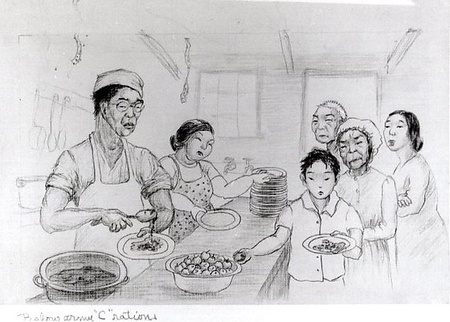

There were lines for everything: for mail, shots, at the pharmacy and clinic, at the mess halls. There were lines for toilets, showers, and laundry tubs. Everything was communal. No secret was safe. Every cough and quarrel was heard in the next barrack. Only the trauma of betrayal continued silently.

But in the spirit of shikataganai or “making the best of it,” we bounced back. We formed softball teams and played intramural games. We produced talent shows. We set up libraries, beauty shops, cooperatives, flower and sewing classes, art and drama departments, dug swimming holes and so on, and boy scouts continued to march with Old Glory fluttering high.

We published mimeographed bulletins. Ours was called The Poston Chronicle.

Four of us worked as artists at the Chronicle. We were young inexperienced kids cutting mastheads, lettering, and sometimes drawing caricatures and cartoons. Only one of us was good at it so he did most of the work. This was such an embarrassment to me, I took a course in cartoon drawing at the Poston Art Department.

Howard Kakudo was the instructor. Howard had worked at Disney’s for two years on Pinnochio’s Blue Fairy. He also drew beautiful pastels of movie stars for theatre displays. He was a professional artist—a rare breed. He was good-natured and extremely handsome; maybe someone’s Robin Hood but not mine because he was older, but more important, the women who flocked to his classes were beautiful and sophisticated (though their motives blatant) and I was only a tumbleweed.

Other staff members were Frank Kadowaki, a quiet married man, and an intense fellow named Larry who was aggressively committed to steering us to non-representational art. Still stuck in “real” and “pretty.” Most of us were intolerant of his ideas; his pushiness turned us off. He was, in today’s jargon, not “cool.”

Mysterious, half-Japanese Isamu Noguchi was already an acclaimed artist. He tramped the desert collecting ironwood and in his pith helmet, high-top shoes, and dusty denims, he sometimes dropped by to see Howard. Or maybe to study the array of pretty women. They said his father was famous and I was sure he was the son of Dr. Noguchi of The Book of Knowledge but my friend Hisaye said not so. Howard said Noguchi was making masks with the ironwood, and indeed, the front of barrack was covered with huge fearsome African masks. Much later, Howard told me Noguchi took them all to New York and sold them for thousands of dollars.

Maybe he was getting rid of memories of Poston. Rumors of his unceremonious exit from camp were persistent. An irate husband, they said. Many years later I went to Noguchi’s lecture at UCLA and among the slides was one he called Poston. Did I see a small breast in the gentle rise at the base. He clicked it by so fast, I couldn’t be sure.

My friend Hisaye Yamamoto covered the art and drama departments for the Chronicle. Since then she’s become an internationally respected short story writer, but she put up with me (as she does now), a lonely depressed adolescent, and she let me hang out with her. Through Hisaye, I learned about other Nisei writers and artists who were even then recording their feelings about the “experience.” I didn’t find them myself.

On the covers of Trek, we saw Mine Okubo’s claustrophobic look of camp life and the make-do spunk of people whose holiday spirit would not be suppressed. She endured the wind and dust and isolation and tramped through Topaz putting it all down. There were stories of the identity before it was called the “identity problem.” It was an education.

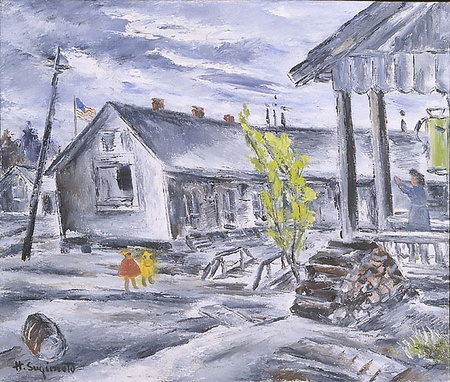

Years later, I learned of other camp artists, of the tragic life of Estelle Ishigo, the loneliness calling out from her drawings. One painting by Henry Sugimoto brought back the smell and sounds of camp—the season: edge of winter, frost on the breath, a dying pipe, hammering in the distance, warmth under the pea coat. It was painted on mattress material and the woven blue stripes of the ticking brought it all back home.

When I was a grown woman I sent my only child to school and returned to painting. In the adult education class, I met three Issei. One was Mrs. Yamagishi, at the time already ninety-four. Somehow, indelibly stamped in her data bank was a picture of her childhood that found its way into every painting she made. The tired white models who sat for us always had cherry blossom cheeks and shining eyes. Pink and red collided with green turquoise. Unsullied by pontification, the paintings sang with child-like joy.

Mrs. Hosoume, then in her eighties, was an accomplished painter. After camp she studied with Taro Yashima. In her painting of a lantern, one can sense a person who, in the age of electronics, clings to a rusty lantern that once lit her nights. It speaks of a time gone—a gossamer memory remaining.

Mr. Abiko was in his late eighties. When I met him, he was working with geometric shapes and basic colors – a little like Mondrian. His paintings were beyond me, but once in a while I’d feel a certain fire. One day I persuaded him to show me his collection. Among the abstracts I found a camp painting carefully wrapped in tissue paper. It was a piece of Mr. Abiko’s history—the years of his life in a barrack home, the flowers he’d potted set on the splintered porch. He had caught the morning light that slipped past another barrack and lit the flowers. “I will never paint like that again,” he said. I wanted to cry.

Now Mr. Akibo’s sky has turned dark. Mrs. Yamagishi’s too. Mrs. Hosoume is ninety –nine. For them, supper streams over an open fire and love waits.

Well, they say all life is terminal. But each of us wants to leave a stone that says, “I have been here.” An artist suspends a moment of his inner life – a fleeting moment of passion and longing in life and puts it on a canvas for us.

* This article was originally published in The View From Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942-1945. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum; UCLA Wight Art Gallery; UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 1992.

© 1992 Wakako Yamauchi / Japanese American National Museum, the UCLA Wight Art Gallery, and the UCLA Asian American Studies Center