Bismillah irRahman irRaheem

In the name of God, the Beneficent and the Merciful.

Tuesday morning last week (June 26) a group of activists and allies from groups such as CAIR-WA, Densho, and faith leaders from multiple backgrounds and beliefs converged at the William Kenzo Nakamura building to deliver street-level dissent against the recent SCOTUS ruling regarding the latest Muslim ban. Having attended at short notice, I—a mixed-race, fourth generation Japanese American Muslim woman—did not prepare anything apart from my presence simply being there, but suddenly I found myself with a microphone in front of a crowd, reiterating how a repeat of Japanese American history — my personal family history — will have consequences far beyond the now for my personal faith community that is the American Muslim community.

Since I did not have a written speech, let this be my written speech. There are a multitude of things I see as both a Japanese American and a Muslim woman that I want to be recognized.

The countries on the ban include Iran, Yemen, Syria, Somalia, Libya, Venezuela, and North Korea (Chad was on the list but got removed). Over half of those countries are Muslim majority, and all of them target people of color. This also demonizes the communities already here as it paints them as a threat; if Trump truly wanted to fight terrorism, he’d invest in fighting domestic terrorism from right-wing groups rooted in White Supremacy, as the evidence suggests doing.

The ban is inherently classist as well, as it includes countries that are ravaged by either war, famine, disease, corrupt government, or crumbling economies. Any sort of future in these places is difficult or impossible, yet the ban excludes Muslim majority places that have Trump foreign investments. Moving somewhere with promise of a better life is often the only way out for many who are now barred from doing so. So much for welcoming the tired, the poor, the masses yearning to breathe free.

This is still a Muslim ban; just look at the first iteration. All the countries in the first ban were Muslim majority. Non-Muslim majority places have been added as politics simmered there, but still over half of the countries on the current ban are Muslim majority. This makes it easier for government and fringe-groups to openly discriminate against immigrants from those places who are already here, using the veil of “national security” to paint these communities as predisposed to violence because of the religion, race, and the actions of strangers in their home countries, just as the Japanese American community endured during World War II and afterward.

Most importantly though, the effect of this policy will affect not just people alive, but their children, and their grandchildren.

Like I mentioned at the foot of the Nakamura building on Tuesday, many of the families from Japanese incarceration camps didn’t recover; everything was taken from them and the add on of cultural genocide affected the mental health of the community. Much like the Native Americans who were banned from their own culture, Japanese Americans were effectively taught that their own culture was shameful, and to abandon it in favor of White American culture: the language was not passed on, the principles of their culture were shunned, and any cultural artifacts were either destroyed, lost, or sold. A part of their core identity was forcibly taken from them and the identity crises I endured later in life were a direct result of that: I would ask myself if I was Japanese enough because I didn’t know the language, I was just Japanese by blood. Was it okay for me to even say I was Japanese? I didn’t even own a kimono; my family didn’t have one. My father grew up on dirt floors with shoes that didn’t fit and wouldn’t buy himself new things because he thought of himself as a second class citizen. My grandmother refused to speak the language, and the mental health of our family deteriorated as a result of our livelihoods and identities being criminalized.

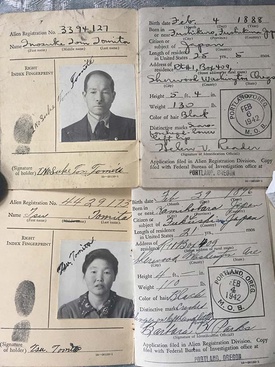

My grandmother and great-grandparents were sent to the same camp as William Kenzo Nakamura, the namesake of the building I stood in front of. It pains me that the pain my family endured has been forgotten, that Nakamura’s bravery has been forgotten, that we are repeating history by trying to deny the identities of American Muslims as not being “American enough,” especially if they come from particular countries. I think of the faces of my great-grandparents on their curfew cards issued during the war, the disgruntled look of my great-grandfather Inosuke and the bewilderment in my great-grandmother Tsu who never thought the country they loved and trusted, the country that gave them life, could betray them so harshly as to call them criminals for what strangers from their birth country were doing.

Immediately following the ruling, mosques around the Puget Sound Area began hosting “Know Your Rights” seminars for those affected. Around the country, Q&As were being held with legal departments and civil rights organizations at Islamic centers. Friends and families who I know within the community are permanently fragmented as now dear members of their family are prohibited from reunifying simply because of their national origin, and more importantly, their religion. In other words, we are being told that because of our Muslim identities, we are not allowed to carry the badge of “American.”

I’m watching my adoptive community getting treated just as my family did: calls for surveillance, calls for curfews, calls for camps because Muslims here are not loyal somehow. And now I wonder, will history repeat itself? Will I go through what my family went through because of my religion? Has the tragedy that my family went through been that forgotten?

When the Japanese American community cries out against the Muslim ban, we are crying out against the injustice that is what happened to us and countless other minorities: the sanctioning of the illegality of our identities. Don’t let history repeat itself. Stand up for your Muslim neighbors, even if you do not understand them, because their Muslimness is just as American as your own brand. Go to a mosque. Meet the community. Be there with us, because no one was there for my family when we lost everything.

* This article was originally published on the International Examiner on July 2, 2018.

© 2018 International Examiner