And did your mother work in camp?

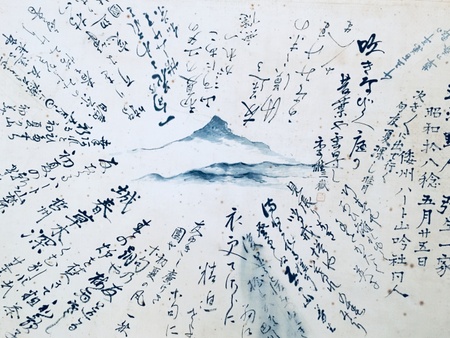

You know, she was doing embroidery here before they went to camp. Oh, this is when we’re leaving Heart Mountain. There was a Mr. Kinushita. Being it’s a desert area there’s a lot of Jasper rocks and dinosaur bones sometimes. And Mr. Kinushita started a rock group so they can go outside the campground and look around the desert area for rocks.

Adina: Oh, is that how they got started in all that?

Yeah. So Mr. Kinushita made arrangements and Grandpa was right away into this thing. But I think it was just one season we were there, we left camp early. We were one of the early ones to leave because we had a minister friend here that was at the church, our minister, he went to Utah and that was before the war. And I guess my father was in contact and they said there’s work out here and you could live out here. So I guess after I got sick and all the things happening with my brother, I remember Mom had to go look for my brother all the time, he gets beaten up by big boys.

In Utah?

No, in the camp, in Heart Mountain. So when he didn’t come home from school she had to go down into a different block. I was the next block, my school. But for my brother it was further down somewhere and she found him in a ditch, you know he was much smaller, but he was like a weakling, kind of a little boy, not the way he is now but when he was little.

So he was getting picked on.

Yeah, the big boys would pick on him. The one thing in Heart Mountain though, between the two mess halls we were divided A and B, and A was the lower one and B was up here. But in between the space, they used to put water in there in the winter in that spot and we used to ice skate. And Grandpa, too. We had the Montgomery Ward order book. They all ordered clothing and ice skates. So that’s where Grandpa learned to ice skate there.

And so they went to Utah and what kind of work was it?

Oh it was farming. But the minister friend that had left here could be our sponsor. You had to have someone sponsor or you couldn’t leave. So we went to Utah by bus, I remember, up through Idaho. From Wyoming up to Cody, and Idaho and then down to Utah somehow.

That’s our log cabin. They said they found a house for us so we go out to Utah, and we find it’s a log cabin. The log cabin was one building from there they had another attachment which was the bedroom. It was too cold so we always had to stay in the log cabin with the big iron stove.

Who drew this?

Oh that’s my father.

There was a big barn, and we had chickens. It was so cold that we had to have the chicks all stay in our log cabin.

You could not escape the cold, and growing up in L.A., that must have been awful for you.

It was cold, it was near Idaho. And we had no running water so we had to go to the well to get our water out. We had a bucket of water in the kitchen, it would freeze during the night and you had to break the ice to do the wash. And then the kerosene stove because no gas or anything. We had electricity. I know my brother used to help me too, we used to get the washtub, put the water in and put it on top of the kerosene stove, go out to the well to wash on a washboard. Then dump the water some place around there then get the well water to rinse.

It was a lot of work.

It was.

But there were more Japanese, you were around the Japanese community though in Utah?

No not really, but there were Japanese living here and there in spots. They didn’t own anything but they were working as farmers. So when it came to picking fruit that was great, we went to pick cherries and Mom and Pop took us, so we were climbing inside the tree to pick the cherries, eating half of it. And my father and mother, they would go outside and pick it on a ladder. My dad would pick the tall ones because it was a big tree. That kind of time is springtime, around May. So the harvest is hard, they even let the school out. I used to go to this Elwood School, and it was only four rooms. And we had everything from kindergarten up to eighth grade. Two grades in each classroom so they had the older ones help, too.

To go help with the picking. If you were to think about your parents, I don’t know if they ever talked about what was happening. Do you get a sense that they felt a certain way?

I know my father said that he didn’t believe that camp life was good for the children. That I remember. So we went out to Utah because we had this minister friend there, said there’s a house out there that’s vacant. So I guess we were one of the early ones to leave camp past that first winter, and went out.

So that was his theory, that being in camp wasn’t good for his children.

He said that it wasn’t good. That’s where I got all that sickness and couldn’t get help and I guess they thought I was going to pass on because I remember having these strange, weird nightmares, I had such a high fever they couldn’t get the fever down. So they said that they were afraid they were going to lose me but somehow I made it through, Mom nursed me through. But I still had awful dreams of all those things.

But coming to Utah it was more moderate, it’s not the desert life, you know in Heart Mountain? I remember, you’re trying to walk to your barrack but the wind would be just so powerful it would just push you back more. Then all of a sudden these big tumbleweeds would come right at you, rolling all over the place. And sure enough one of them would come and hit you, and they’re as big as you are. So you had a hard time trying to even get home. Or if you went to a class you know, there was an art class. And Grandpa and I used to do things more together, maybe that’s why I’m closer to Grandpa. He used to take me, you know? So we were doing drawings. These tumbleweeds, I thought oh my gosh.

Yes. So harsh and that wind is awful.

That desert, really was–it was hard, I don’t know how people survived it.

We take a break, and then pick up the conversation with Lily’s wedding album from 1952.

So she said you had a story about your wedding dress?

Oh. I got married when I was a teen, yet. Everybody else was going dancing, all having their fun but I don’t know I got married–

Adina: Right after you graduated right?

Yeah, right after we got back from camp. Oh, that dress?

Yes.

It was actually my school prom, we always had a prom in your senior year? So at John Marshall over there, I had Mother make me my icy blue, satin gown, strapless. I never had things like that. So she made all that for me. And I used that as my undergarment and then had her help make the top, organza one. She made all that.

How did you and Clarence meet? You were very young.

I was too young to know anything, I had never been out for a date. But he was a member of the church in the early days. So he was about twelve years older than me. He was a much older man but he went to WWII and was in Germany. And I was still in only high school.

How did you get introduced?

He came to the church one day and I used to be the organist. Because I used to play the piano when I was a little girl. He was already in his thirties, and I was only–

You were 18?

Something like that.

But you must have gotten along?

You know, it’s funny. He gave me the ring, I never told grandma. But he gave me the ring he told me to wear it. The engagement ring or whatever it was. But I asked him to talk to, or show it to Grandma and Grandpa, he wouldn’t do it. So I should’ve known then that he’s a stubborn, hard man to deal with. If I know now–but at that time, I didn’t know what to do.

So when Grandma and Grandpa had a rock club, still continuing from Heart Mountain? People were gathering at our house. Oh, it wasn’t the rock club, it was a church prayer meeting. And I had the ring hidden because he gave it to me to wear it, and I said it’s not for me to wear it like without making arrangements with my parents. So I wouldn’t wear it, so I had it hidden in a drawer in my bedroom. But then one day he said his friend from Chicago was coming to visit him there [at Lily’s parents’ house]. And he told him about the engagement kind of thing. But I said, you got to talk to my parents. I didn’t know what to do I was caught in-between. But, I got the ring and put it on myself that night because the church people were all there. And they met every week, or every other week, and on that particular night, it was at my mother’s house. And I put the ring on, just to please him because he told his friend that he got engaged. So put it on, and the unfortunate thing was, Mrs. Kagiwara one of the church members noticed the ring on my hand but my parents didn’t know anything about it. It was an embarrassing thing.

Adina: It was quite scandalous, huh?

Yeah, I just felt I didn’t know what to do, but I didn’t want to upset him. But he said, ‘It’s none of their business’, kind of thing. I should have known then, if he said it’s none of their business, but his friend is coming to see him there. I learned from that then, that you can’t–you know, I’m too naive. And it was too late. Church member goes and congratulates my parents.

They didn’t know.

They didn’t know anything about it. He didn’t even talk to him either.

That’s strange.

He told his friend but he doesn’t even talk to my parents. So I didn’t wear the ring, he gave it to me to wear. So it’s only convenience whenever, kind of thing. So he put me in a spot always, but he was about twelve, thirteen years older than me, so he just did anything what he pleased. I didn’t think I’d have that kind of trouble. He made it hard for me, in many ways.

And you think that was because of the age?

Yes, he was in WWII, he was in Germany. So he was much more arrogant. But why he was so set on me, that I don’t understand either. I never went out with anyone before. And I thought he was a decent man. But I should’ve learned from the way he was talking to me and treating me, you know. You don’t do things like that. I don’t know why he was convinced that he was going to marry me, that’s all.

Adina: One of my mom’s cousins said that my grandmother, she was the prettiest woman he ever saw. So I think he was just attracted, definitely.

It’s funny, he knew he would have to meet your parents and talk to them. But he made no effort.

He was just in his own way–

Adina: Well my great-grandmother was a very scary opponent, so I could see how he would want to just try to scoop her up and elope, type of thing.

Wow.

I should’ve known better then but not going out for dates and we didn’t know the etiquettes. And I was more scared of him.

Adina: Yeah so my mom had grown up in a situation where it was really challenging. Because here she’s hearing all these stories of her father stole my grandmother’s youth, her best years, that type of thing. And then with my grandfather, he had remarried, so there was never the relationship she was looking for from him.

Right, it was with his new family. And did he have children?

I don’t think they had children. I think my mom was his only children. There was just no real relationship between them. I remember her trying to connect with him and everybody categorized Clarence as like a big talker, that’s what everybody would say about him.

Like charismatic?

Adina: Yes, exactly. But when I was cleaning out the house when I first moved back to L.A. after college, I had found a bunch of my grandma’s love letters, or correspondence back and forth to him. But there was a stack of letters that my grandma and Clarence were writing back and forth to each other. Probably when he was serving, right? You guys were writing back and forth a lot?

Lily: Well that’s when, I think because I didn’t hear from him, after I left home to live with him, he’d do things, and then he’d get upset and he’d leave house. And I don’t know if he’s ever going to come home. And one time I was in Darice’s crib, crying and sleeping. And I thought I have got to go find a job I don’t if he’s going to come home, how I’m going to pay the rent. I walked over to the nursery school, I don’t know how I found out there was a nursery school by going over the bridge and walking over to the other side. But that’s where I left her and got on the Figueroa bus and Broadway department store is a place where I always used to go shopping so I just asked for a shop of anything, then they said they liked me, I was dressed in my suit. They gave me the window job right away.

Things are so different now, aren’t they? So did he leave that time?

He came back after a while, I don’t know how many months later after I already got my new job and taking the bus and doing things. Because he took all the bank book, the car keys, things he said all belonged to him which is true, I wasn’t working. And it was his but I had nothing. So that night I called Grandma and she brought me a bag of rice but that’s not enough to feed Darice and me, she was just a baby. And I took her to school and she hung onto my legs saying, ‘Mommy, mommy,’ and I cried, too. And he’d come back and stay for a while, and then take off.

And you wouldn’t know where he’d go?

No. He takes all the money and everything.

Adina: So we grew up hearing these stories.

Did he come home with post-traumatic stress disorder from the war?

I have no idea. Personality, I think.

Adina: A little bit of both, I think.

And then after he came back the last time said he wanted to go to Alaska to do this job, they were making a radar station from one end to the other of the United States. They called it a certain name, they were afraid of Germany or Russia attacking or something. So they were building that station and he said he would make good money, maybe we could build a house but that didn’t happen.

To be continued...

*This article was originally published on Tessaku.com on May 13, 2018.

© 2018 Emiko Tsuchida