There are festivals, public baths, kabuki, and "little Japan"

The International District is located south of downtown Seattle. In one corner of the district remains Japantown. At its peak before the war, around 8,500 Japanese immigrants lived and ran businesses there. An intern from the North American Post Agency traces the origins of Japanese immigration to Seattle, the glorious era, and the vestiges that remain today.

History of Japanese immigration dating back to the 1880s

Did you know that Seattle once had the largest Japantown in North America? In 1930, about 8,500 Japanese people lived there, making it the second largest in size after Los Angeles. Japanese-run shops were concentrated around the International District, especially Jackson Street and Main Street, and residential areas with many Japanese residents spread out to the east.

The history of Japanese immigration in Seattle dates back to the early 1880s, about 30 years after the first white settlers landed in Seattle in 1851. Seattle prospered at the end of the 19th century thanks to the flourishing forestry and coal mining industries in the surrounding areas, and the opening of the railroad in the 1870s. In 1880, Seattle was a small pioneer town with a population of about 3,500, but by 1890, the population had rapidly increased to about 40,000. By 1910, after the Alaska Gold Rush, it had grown into a city with a population of about 230,000.

The first Asian immigrants to increase Seattle's population were Chinese immigrants. According to historical records, in 1876, a Chinatown was formed in a corner of Pioneer Square, where about 250 Chinese workers lived. However, a violent anti-Chinese movement by white immigrants in 1886 caused many Chinese immigrants to flee to their home countries or to San Francisco. Meanwhile, Japanese immigrants increased in number to make up for the sudden decline in Chinese workers.

The largest minority group in Seattle

When Nippon Yusen started its service between Seattle and Yokohama in 1896, the Japanese immigrant population increased rapidly. For about 10 years, until the Meiji government imposed voluntary restrictions on immigration to America under the Japan-U.S. Gentlemen's Agreement in 1907, many young Japanese men crossed the sea in hopes of making a fortune. After the Gentlemen's Agreement, the number of male immigrants decreased, but Japanese women began to migrate to Seattle as brides for them. They were so-called "picture brides." Female immigrants continued to increase until the Japanese Exclusion Act of 1924. In 1910, the Japanese population in Seattle had a high male ratio of about 5,000 men to about 750 women, but by 1920, it had decreased to about 4,000 men and 2,000 women. In this way, the first generation of Japanese who crossed the sea built families and raised children in Seattle, forming a Japantown.

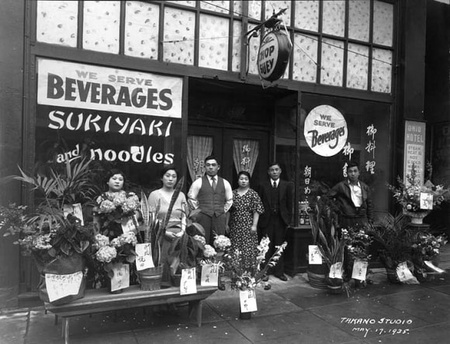

Japanese immigrants enjoyed great economic prosperity, backed by the size of their population, the economic growth of their home country, and the success of farmers who had moved inland and agricultural product traders. Of course, the Japanese people's hard work also played a part. Japantown flourished as a reflection of the success of Japanese immigrants. The Japanese consulate was established in 1901, and the publication of the North American Times, the predecessor of the North American Post Company, began in 1902. Advertisements in the North American Times show a wide variety of businesses, including restaurants, hotels, barber shops, greengrocers, lawyers, and doctors, conveying the vitality of Japantown at the time. There were also banks and schools, and festivals and Bon Odori dances were held on a grand scale. As is typical of Japantown, there were several public baths. The Japan Hall Theater, which opened in 1909, hosted performances ranging from kabuki by local entertainment societies to performances featuring famous Japanese singers. A small Japan was truly found there.

The deterioration of US-Japan relations and the decline of Japantown

In 1909, a Japanese pavilion was set up at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition held on the current campus of the University of Washington, and there is a record of a business delegation led by Eiichi Shibusawa participating in a parade. The friendly relationship between Washington State and the Japanese government also contributed to the thriving Japanese community in Seattle.

Things started to change around the time of the Great Depression in 1929. Around the time of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the outlook for Japan-U.S. relations started to turn sour. More and more people returned to their home countries, and the Japanese population fell to about 7,000 by 1940. Then, in 1941, a few months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Japantown disappeared within a few days.

Wartime and Postwar Edition >>

References

Taylor, Quintard. The forging of a black community: Seattle's Central District, from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era . (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994)

Chin, Doug. Seattle's International District: The making of a Pan-AsianAmerican community. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002)

Seattle: International Examiner Press

A chronology of the history of Japanese immigrants (prewar)

| 1850s | 1851 | Settlement in Seattle begins |

| 1860s | 1860 | The first Chinese immigrant, Chin Hock, establishes a Chinese immigration agency. |

| 1870s | 1873 | Northern Pacific Railroad opens to Seattle |

| 1874 | Businessman Henry Yesler becomes mayor of Seattle | |

| 1880s | 1881 | The first Japanese immigrant, Nishii Kyuhachi, arrives at Seattle Port. |

| 1886 | The anti-China movement caused a sharp decline in Chinese immigrants. | |

| 1890s | 1896 | Nippon Yusen begins Kobe-Yokohama-Seattle route |

| 1897 | Alaska Gold Rush Great Northern Railway Recruiting Japanese Workers | |

| 1899 | Japanese Association Founded | |

| 1900s | 1900 | The Oriental Trading Company arranged for Japanese immigrant workers from Shizuoka. |

| 1901 | Japanese Consulate moves from Tacoma to Seattle Seattle Honganji Betsuin temple is built | |

| 1902 | Seattle Japanese Language School (the oldest Japanese language school in the United States) opens. The Japanese newspaper "Hokubei Jiji" was launched (until 1942; from 1946 it exists as "Hokubei Hochi"). | |

| 1904 | Japanese restaurant "Maneki" opens (still in existence) | |

| 1905 | Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun launched (until 18) | |

| 1906 | Jackson Station construction completed | |

| 1907 | Gentlemen's Agreement between the United States and Japan Japan Pavilion Theater opens (building still stands) | |

| 1908 | The Seattle Japanese Association was founded. | |

| 1909 | "Japan Exhibition" attracts attention at Alaska-Yukon Pacific Exposition Japan Pavilion Theater opens | |

| 1910s | 1910 | Panama Hotel opens (with Hashidateyu in the basement) Japanese newspaper Daihoku Nippo launched (until 1942) |

| 1911 | Union Station construction completed | |

| 1912 | The Japanese Association and the Seattle Japanese Association merge to become the Japanese Association of North America. Japan, from the Meiji to the Taisho era | |

| 1920s | 1920 | The Japanese Exclusion Act bans all Asian immigrants. |

| 1926 | Japan, from the Taisho to the Showa era | |

| 1929 | Great Depression | |

| 1930s | 1932 | Higo Variety Store moves to its current location |

| 1935 | Washington State Anti-Intermarriage Movement Begins | |

| 1937 | The Second Sino-Japanese War begins. Friction arises between Japanese and Chinese immigrants. | |

| 1940s | 1941 | Attack on Pearl Harbor, outbreak of war between Japan and the United States |

| 1942 | The Japanese American Internment Order (Special Executive Order No. 9066) is issued. |

*This article is reprinted from Seattle lifestyle information magazine Soy Source (May 26, 2017).

© 2017 Soy Source / Misa Murohashi, Megumi Matsuzaki, and Mao Osumi