One intriguing window into the world of John Okada’s landmark 1957 novel No-No Boy is the study of how it was first received. An exploration of comments by reviewers of the initial edition reveals the prevailing climate of opinion regarding wartime Japanese American experience, and provides evidence as to how the work was understood at the time of its creation. These are not simply matters of historical documentation or literary criticism. Part of the legend surrounding No-No Boy is the idea that its initial publication was deliberately ignored and its author subjected to a campaign of silence by hostile Nisei, and that as a result the book failed to catch on among readers. True, no reviews appeared in the English sections of the daily or weekly Japanese American press, but such silence also reflects the reality that in those days the Nisei press, including the nationally-based newspaper Pacific Citizen, lacked literary pages and did not do any book reviews. In general, critics remained starkly divided over both Okada’s literary skills and his portrait of the racial prejudice and internal conflict to which Japanese communities were exposed. A separate issue was the manner in which reviewers recognized the distinction between the “no-nos” who gave unsatisfactory answers on the loyalty questionnaires in camp and were segregated at Tule Lake, on the one hand, and the draft resisters on the other (a confusion prompted by Okada’s title that has bedeviled readers ever since).

No-No Boy was published by the Charles Tuttle press in both the United States and Japan, and was reviewed in publications around the globe—Japan, Hong Kong, and Canada as well as the USA. The first reviews appeared in Japan’s English-language press during May and June 1957, presumably in response to review copies sent out from Tuttle’s Tokyo office. These critics all tended to minimize Okada’s craft, even as they recognized his achievement in jump-starting Japanese American literature by focusing attention on the wartime events.

For example, a review in the June 2, 1957 issue of Mainichi Shimbun by “B.L.M.” asserted that the book was more of a “tractate” than literature. “This is a story with a purpose, a purpose so insisted upon, and so repeatedly, that it overwhelms the plot and the characters.” Similarly, in the May 24, 1957 issue of Japan Times, an anonymous reviewer [likely Ken Yasuda, a poet and former inmate from Tule Lake who was a Tuttle author] proclaimed, “By no means can Okada’s novel be classed side by side with the best in literature. Its importance, however, is more historical. Being a first, the book marks a turning point in the efforts of the Nisei for expression through writing.” The reviewer concluded that No-No Boy presaged a bright future for Nisei literature.

One rather unusual review appeared in the May 12, 1957 edition of Yomiuri Japan News. Its author was John Fujii, a journalist who had grown up in Alameda before migrating to New York and then to Japan and Singapore during the 1930s. Fujii, perhaps giving vent to his own demons, complained that Okada’s work was “soap-box oratory” on the subject of racial discrimination. “One wonders why the Japanese-American society is filled with such bitterness when they have inherited the heritage of America. This is the adjustment of many minority groups. It’s no worse than Saroyan’s Armenians, Steinbeck's Mexicans and Faulkner or Tennessee Williams’ ‘southern trash.’” (despite Fujii’s working primarily in English, he does not seem to associate himself with Japanese Americans). In contrast to the Nisei, whom he presented rather disdainfully as a “lost generation” within a country that refused to accept them, he pointed to those like himself who had given up on America, returned to Japan and settled easily into being Japanese. “Few of these individuals will admit any regrets, if they have any, at this late stage.”

Contrasting strongly with Fujii’s review was one that appeared a month later in the Asahi Evening News. It appeared under the pen of French journalist Alfred Smoular, a wartime resister and survivor of Auschwitz who moved to Japan after the war as head of the Tokyo bureau of Agence France-Presse. In his analysis, Smoular stated that the novel had no conclusion, apart from a faint note of hope, and should thus be considered more a document than a novel. Smoular likewise underlined the peculiarly (Japanese-)American nature of the story. “While it is not certain that all Americans were…aware of the question which is the subject of ‘no-no boy,’ it would be difficult to understand it, socially and psychologically, out of its national background. For many European readers, for instance, the hero of the novel would have had valid reasons for refusing to be drafted with his parents in camp and he would not have been psychologically confused.”

Another intriguing review ran in the U.S. Army Newspaper Pacific Stars and Stripes (a newspaper whose Tokyo edition was edited during the early 1950s by the late Nisei journalist Yoshiko Tajiri Roberts). Considering that the newspaper served a military audience, reviewer Richard Larah provided a surprisingly sympathetic account of the work. Rather than condemning out of hand a tale of a draft evader and his resistance, Larah instead praised the author’s craft and approved his discussion of injustice: “A powerful novel, “No-No Boy” presents the entire subject of racial prejudice in America in a dramatic manner.” Almost simultaneous with Larah’s review was one in the Hong Kong-based English daily South China Morning Post. The Post’s reviewer, “K.C.W,” underlined Okada’s status as a potential spokesman for the Nisei group, and underlined the hopeful vision for a racially inclusive future that the reviewer located in Okada’s conclusion.

The first North American review of the book appeared in July—not in the United States, but in the Toronto-based Japanese Canadian weekly Continental Times. (While the text of this review was so positive that the publisher excerpted it for use as part of the book’s publicity package, the site of the review remained obscure for decades, until I uncovered it several years ago while reading through back issues of Japanese Canadian newspapers). Writing for an audience whose members had experienced mass confinement in British Columbia, the reviewer—a Canadian Nisei man by inference—expressed particular admiration for Okada’s literary style and presentation. “Although the author seems to have selected an unusual theme in which to portray the central figure of his story and leaves the reader with many questions unanswered, a situation which favors a dramatic approach to a realistic one, he has done commendably well in enlarging upon that theme. As a work of fiction, the book is immensely readable, which after all is a good test of any writing.” Indeed, the reviewer closed on a wistful note, deploring the lack of literature regarding the Japanese American and Japanese Canadian wartime experience. (In that respect the review proved prophetic—even as Okada’s No-No Boy was rediscovered and republished during the 1970s, Japanese Canadian author Joy Kogawa’s powerful novel Obasan appeared. It soon became not only a leading fictional representation of mass confinement in Canada, but a rare Canadian text adopted by American critics and educators).

No-No Boy was published in the United States in September 1957. That same month it was discussed in a pair of notable reviews in American publications. First, the Saturday Review featured a critique by Earl Miner, a UCLA (later Princeton University) professor and scholar of Japanese literature. More than other reviewers, Miner clearly recognized that the book’s action took place against a background of official injustice—he referred starkly to the Japanese Americans “whom we herded into concentration camps”—and he clearly picked up on Okada’s audacious goal of providing an analysis of America itself as both hero and villain of the piece. Yet Miner’s evaluation of Okada’s novel as a work of literature was more uneven. He appreciated the novel’s structure and referred to it as “absorbing,” but also stated (in a somewhat patronizing tone) that it descended into “strained melodrama.” In a historical irony, Miner described No-No Boy as the best of its class, and an advance in the literature, not knowing that it would also be the last novel on wartime confinement to appear for a generation. Meanwhile, No-No Boy was reviewed by Nisei writer Alan Yamada in the Catholic serial Jubilee. Yamada admired the tone and Okada’s overall message, though he questioned the author’s prose style: “Okada writes with the raw fury of James T. Farrell about his angry group of ‘Japs’ and ‘Americans” and the tensions they experience among whites, Chinese-Americans and Negroes. Though his writing is often awkward and confused, you know that these are real people who fill his novel and that they have something to say about the way life has treated them.”

As mentioned, the Nisei press did not feature any formal reviews of No-No Boy, though there were various references to it. For instance, the North American Post, a Japanese-language newspaper in Okada’s home town of Seattle, featured a brief article on the book in September 1957. The piece offered a straightforward summary of the novel, then added an explanatory note: “The stories about Yamada and the other characters’ struggles are based on real events around the Japanese community. The title ‘No-no’ is representative of those who resisted the war and were denied by society.” Meanwhile, a pair of articles mentioning the book in passing appeared in a short-lived English section that the newspaper offered.

The only significant print analysis that the original edition of No-No Boy received, and the final word on the work for several years, was an account in columnist Bill Hosokawa’s biweekly Frying Pan column in the September 27, 1957 issue of Pacific Citizen. Getting reviewed in this column would have been considered quite a plum for Okada, as Hosokawa was as a JACL stalwart. What is more, as editor-in-chief of the Heart Mountain Sentinel during the World War II, Hosokawa had faced off against both dissidents at the time of the loyalty questionnaire and the future Draft Resisters of the Fair Play Committee. Hosokawa (who confused the ranks of “no-nos” and erroneously described Ichiro as a Tule Lake segregant) is clear in his disdain for “no-nos,” yet offered measured but sincere praise for Okada’s literary craft and “the understanding and insight” he brought to his characters.

Still, two curious features of Hosokawa’s piece are worth noting. First Hosokawa made the shocking (perhaps rhetorical) statement that in the 12 years since the end of World War, he had never once met or spoke with a no-no boy or draft resister about his experience. This points to the continuing division and mutual hostility within postwar Nisei circles that the government’s wartime actions, and the decisions that Nisei were pressed to make in response, left on community members. Meanwhile, even as he praises Okada’s authentic characterizations of Seattle community lingo and mannerisms, Hosokawa (by then living in Denver) oddly conceals his own status as a Seattle-born and –raised Nisei: he seems unable to acknowledge that Okada (eight years his junior) hailed from the same small city, and attended the same college.

Okada’s novel, according to its publisher’s later testimony, did not sell well, and both the book and its author dropped as subjects of media coverage. It is impossible to know how much, if any, importance the mixed reviews had on the public reception of No-No Boy. What is notable for our purposes is what the early reviews demonstrate, that readers from the outset found Okada’s work thought-provoking and challenging.

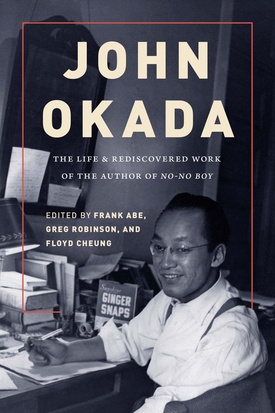

*Greg Robinson is co-editor of John Okada - The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy, a new book due out in July from the University of Washington Press. This article is adapted from a chapter studying how No-No Boy was first received, which was not included in the book due to space constraints. Full text of these reviews can be read on Resisters.com.

© 2018 Greg Robinson