Tsuchida communicates through the project

Diana Emiko Tsuchida, a researcher of Japanese-American history, is currently working on a project called " Iron Fence ," in which she listens to the stories of Japanese-Americans who were in internment camps and shares their experiences and life at the time. Unlike the grandfather of Rob Sato, a Japanese-American artist introduced in Part 1 , Tsuchida's grandfather was one of those who did not pledge allegiance to the United States during the war and answered "NO" to the loyalty registration question. In this second installment, we hear the thoughts and family stories of two people with completely different grandfathers. This time, we bring you the story of Tsuchida's grandfather, Tamotsu.

"No," my grandfather didn't pledge allegiance

Tsuchida started the project "Iron Fence" three years ago. The project began by listening to the stories of Tsuchida's father Mitsuki (81), who was imprisoned in a concentration camp as a child. "I heard that my father had a very difficult time in the concentration camp because my grandfather Tamotsu answered 'No, no' to the questions on the US government's loyalty registration, and the family was considered disloyal."

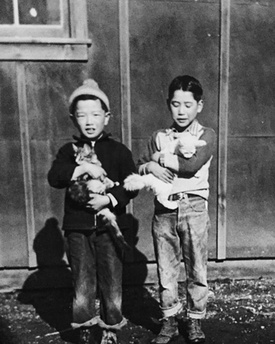

On December 7, 1941, when Tsuchida's father, Mitsuki, was five years old, the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred. Japanese Americans were deemed "enemy aliens" and sent to internment camps in 1943. The U.S. government at the time asked them questions such as "Would you volunteer for the U.S. military?" and "Would you renounce your loyalty to the United States and the Emperor of Japan?" Japanese Americans who answered "No, No" to these two questions were interned at the Tule Lake Internment Camp in California, a segregation center for disloyal people. Tsuchida's grandfather, Tamotsu, was one of them. "Because his family was interned at the Tule Lake Internment Camp, my father told me at the time that he had no good memories."

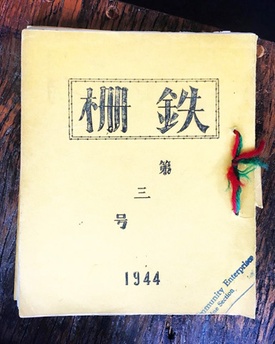

The project name "Tetsusaku" (Iron Scepter) comes from the Japanese magazine "Tetsusaku," which was published for a short period at the Tule Lake Internment Camp and featured poetry, haiku, essays, and more.

As Tsuchida listened to his father Mitsuki's story, he became interested in how Japanese people felt during their days in the internment camps. He gradually began interviewing his father's friends, and before he knew it, the project had developed into one.

Divisions within the community

The family initially lived in San Francisco, but when World War II began they were interned at a camp set up at Santa Anita Racetrack, then at the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah, and finally at Tule Lake after Tamotsu answered "no, no" to the loyalty registration question.

"My grandfather was said to have felt anger towards the concept of justice. He was educated in Japan, so I think that's why he had such strong feelings towards Japan."

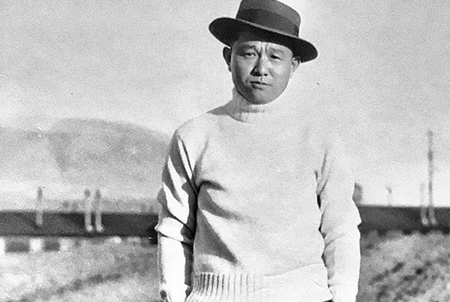

My grandfather Tamotsu, who had moved to the United States and lived in San Francisco, ran an employment agency. However, after the war broke out, the US government at the time took everything from him. "Everything was taken away from him, including his company and his precious camera. My grandfather thought, 'This isn't fair,' and he was not afraid to speak up about it. That's why he said, 'No.'"

Meanwhile, for his father Mitsuki, who grew up in America, the differences in Japanese and American ways of thinking caused inner conflict. "My father was taught by strict American teachers at school. I heard that every morning, students were made to bow in the direction of the emperor. He told me that as a child, he wondered, 'Whether you look to the right or to the left, you see America, so why do we have to bow?'"

I wonder how Tsuchida feels about people like Sato's grandfather who answered "yes" to the loyalty registration question and made a decision that was the opposite of his own grandfather's.

Tsuchida once spoke to someone whose father was a veteran of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and he had heard that those who answered "YES" and served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team would never speak to those who answered "NO" and went to the Tule Lake Internment Camp. "I was deeply hurt by the division between the 'YES' and 'NO' factions that arose within one community," Tsuchida recalls.

"Those who answered 'yes' and served with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team remembered, 'We will fight for our country with our lives on the line. We are willing to die for this country.' Listening to Mr. Sato's story, I was deeply moved by their feelings. At the same time, I have great respect for my grandfather's decision and courage to say 'no,' that he could not sacrifice his life for the U.S. government that had imprisoned them in concentration camps. Now that fewer people know about life in the concentration camps, I want as many people as possible to hear their true voices," Tsuchida said with emphasis.

*This article is reprinted from the Rafu Shimpo (May 9, 2018).

© 2018 Junko Yoshida / Rafu Shimpo