And how was the relationship between your parents? Did they have a good marriage?

I think so but my father was much older than she, but they were introduced by a family friend in Japan but because he never came after her she said it was embarrassing. They were sort of like betrothed. That’s why she says she’s going to go to America herself. So she came on the boat by herself.

Yes. Were they still corresponding though?

I think so. I can’t figure it out how she would have known where to go. But she said she was stuck at Terminal Island, after you get off the boat for so many days, I don’t know for inspection or whatever. But she said she was terrified but Pop didn’t come after her for three days or something and she was very upset.

I wonder–you’re not sure what happened, like if he didn’t have access? He must have known.

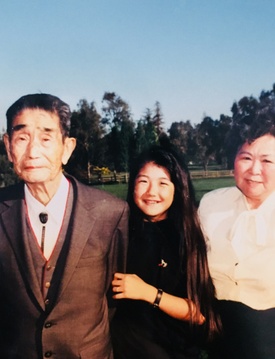

I don’t know how that part works I never asked him. I never thought of asking him at the time. But that was our last Christmas, December before we had to go to camp so my father used to take–his hobby was camera, taking pictures. So he took that and then he was also developing it in the bathroom himself. So that’s one of the last pictures we had all dressed up.

And what did your parents say? Did they explain to you and your brother what was happening or do you remember what happened with Pearl Harbor? You were very young but did kind of know there was something wrong?

No, except that my uncle used to live with us and his mother said she’s ill, so please come home. We didn’t know though, we heard something about maybe a war starting. But he did take the last ship home and that’s the last we heard. We had no further contact because you couldn’t write or anything.

No correspondence.

No, you couldn’t correspond or anything. I guess he said he was taken into the Japanese army immediately and because he spoke and read English, it was an advantage to them. He became something there, I forgot, but he was sent to Burma and that’s where he got malaria, that’s where he was. He looked scrawny. I always thought of him as big, husky.

You remember him as healthy and strong.

I remember him coming after me sometimes at the Micheltorena school, if it rained or something you know, he’ll come after me because they can’t work. He was doing gardening too. So if it rained, he’ll come down and pick me up. So after he was gone, we didn’t know what happened until after the war then we learned about his–but when I met him at Osaka airport the first time.

I was with Japan Airlines and after the first trip over to Japan, I better go meet my grandmother and meet my uncle. And they were all hanging onto the fence looking at the plane because they know that I should be on that particular plane to Hiroshima. But I thought being I was a JAL employee I should let all the okyakusan [customers] go first you know, I don’t know, Japanese mentality I guess. But I didn’t get off and they were hanging on to the fence watching. And they thought, no one came off.

And finally I gathered my stuff and I was wearing my three-inch heels because you know in those days we used to wear big heels. And I was so tall, it was embarrassing because my grandmother was some place down here. She was trying to talk to me and she insisted on carrying my handbag or just travel bag that was heavy. But she was way down here somewhere. Oh gosh that was an experience I thought, ‘I should’ve worn my regular shoes.’ And Japan, my first trip I didn’t know that they had all that kind of wood floor. You can’t wear shoes inside, you take your shoes off.

So my grandmother, my uncle, remember? And he had all this curly hair. And I thought it didn’t look like my uncle at all. But I guess after his malaria illness, his whole body got small and changed. But he had a son that I told you, that he looked like a little midget?

Oh, right.

Yeah, Masaki. So amazingly he just jumped in a car, and my uncle had a car made that everything be done by hand, by hand shift so that he could drive a car though his leg is, he was only so big. And he played the piano for us, and his piano pedal had this short thing, some gadget on there.

They made it work for him. Did your uncle ever tell you stories about what happened to him during the war?

Yeah, in a sense that because he spoke English and understood English, he was put into a different category, of listening to different news things, that’s about what he said. But he was, I think captured down–no he was hiding in the jungle, that’s what it was I’m sorry. Yeah and he didn’t even know the war was over until he said they were so hungry for certain food. I guess they were stealing food during the nights, going out of their hiding to the village somewhere and finding some food and bringing it back. It wasn’t only he, it was probably a couple of others but they used to, that’s all they ate. When you hear this story it’s really sad until one time he came out and found out that the war was over. Finally was able to come home.

So he didn’t know.

And I don’t think he was the only one, there was probably somebody else. They escaped from the Japanese army somehow in hiding, you know.

Oh my gosh.

I mean they should be in the army fighting, but they were down there. I don’t know they said they were in hiding.

Adina: That’s how he got sick, right?

Yeah because they were in the jungle.

Right. That was common everywhere in the Pacific I think, getting malaria.

I guess you never get over malaria, I think.

Adina: I think he had it for so long that by the time he got care for it, it already was a chronic issue.

How sad.

Yeah. But it was nice to just meet the family. I remember the first time we were in Nara, actually we landed in Osaka but we went to Nara. And the Miyako Hotel, it was a pretty place. And to see the screen opening up and you see all of this forestry-like, and there’s hot spring water coming out. There’s a river down below us. But it’s a hot spring water so people are bathing in different little spots. It’s too strange that I couldn’t do that right away but after a while you got more braver, you have to try.

Yes, you have to take advantage of that.

Trying new things, you know. Yeah that night, what surprised me is my grandmother, she was a tiny little woman but when we got to the inn, she stretched out like a lady of leisure and the next thing you know they have these little arm rests or something, and next thing I know she’s pulling out a cigarette and she’s smoking away. It shocked me I thought, ‘Grandma’s smoking?’

Adina: My great-grandmother was very conservative, they didn’t drink, they didn’t smoke.

So this was shocking for you to see.

Actually, Grandma’s sitting there with that arm rest of kind of thing, and pulled out a cigarette started smoking [laughs]. I couldn’t believe it. Like you see the in movies sometimes, you know?

Yes exactly. Well then maybe considering everything she’d gone through.

I guess she was a lady of leisure, or I don’t know.

So that’s good you reconnected with that part of your family in Japan. And then your parents were here and your uncle had left. And then your parents were still here. And I bet they didn’t know either what would happen to them?

They were finally able to send something called SOS, a care package to Japan. Food, sugar. It’s always sugar, I guess we were rationed sugar here, too during the time of the war.

So Mom would always save a ration to send to Japan, some sugar and different canned foods you know, meat cans. And they would send it by sea. They didn’t have airplanes that cheaply so everything was done by sea so it took a couple of months or something to get there, you know. Nothing that would that would spoil.

Finally, I guess working for Japan Airlines I was able to travel my first trip, it changed things for me. That’s all I remember of the trip.

When you were in elementary school here in L.A. before you left, were there other Japanese students?

No, I was the only one in my class. So the teacher probably didn’t say anything and probably my parents never went down to tell them either.

You just left.

Yeah, I was just gone. I just went one day to the last day of school, only it’s my school day, and then I just didn’t go back to school.

Sad. So that’s why she was wondering, where you went?

The parents probably never talked about it, you know? Because of the war. She didn’t know, why would she ask me? After I came back though, after the war ended and I was now ready for junior high school not grammar school no more. And they’ll call you Jap, you know, and that didn’t – you’re trying to find a way to come home so that hillside, I found all kinds of hideaway kind of you know, bushy places. I’ll have to show Adina that one stairway that went up the hill. There was a stairway. It’s also almost half covered with trees and bushes that you could hardly tell, and I used to go sneaking up those stairs to go home. Yeah, all the students walking to school say, ‘Hey Jap you don’t belong here,’ that’s all I remember though. Or they’ll throw rocks at you.

And were you still the only Japanese when you came back or were there other Japanese students?

No, not in my particular school area. Maybe if I was in Boyle Heights or something it’d be different maybe. But where I was was all Caucasian.

You were picked on.

Yeah, because I was the only Japanese. So what’s sad was down below on Sunset Boulevard, there was A&P Market and there was also a food market or something like, anyway two grocery stores and either one you can go to for meat or vegetable, it’s just a food house. Oh, Food House.

But this time I don’t have to cross the street, so Mother would give me a dollar or some money to buy some hamburger meat or something. And you stand there waiting for help but no one pays attention to you. And then some other Caucasian lady would come by and ring the bell because no one is out there. And they’d come out and take care of them and service them then they go back in. And you stand there for the longest time and I used to go home crying because I couldn’t buy the meat, the hamburger meat or something that mother asked me to pick up. There was discrimination, you don’t know how to deal with it.

I didn’t have that while I was in Utah because from Pomona assembly was a short time there. Then we were put on a train. We didn’t know where we were going. We ended up in Heart Mountain, Wyoming and there the barracks were big and far. I remember, you saw this mountain that looks like an ‘r’, and we were close to that other end. And I remember that first winter coming I got sick, it used to get so cold at night and your room didn’t have a warmer. I think there was a pot belly stove but you can’t warm your room. It was a big long barrack with A, B, C the two larger rooms and then D at the end. So two small room for couples, singles and then two middle ones were for families. But we could never could get our room warm enough and I remember I got pneumonia and they couldn’t take me to a doctor because the doctor’s way at the other end of the camp. It was cold, couldn’t get an ambulance, so ever since then I’ve been weak and getting sick.

And so was that the first winter in camp?

Yeah first winter in Heart Mountain.

So you were about eight or nine?

Yeah let’s see, we were in Pomona only a few months, so I was still the same age then because it was going into winter over there. Yeah same age, so I would’ve been in the third grade.

Wow. So got pneumonia.

But they couldn’t get me to the doctor. I guess my mom nursed me, somehow, but since then I’ve been always getting, every winter get sick. And I was always a toughy one, I never got sick, you know? And my father I know, in camp in Pomona, too, he never–you know as a man, I guess they have pride? They never clean toilets or bathrooms. But he got a job cleaning toilets. So he said it was degrading but he did it.

To be continued...

*This article was originally published on Tessaku.com on May 13, 2018.

© 2018 Emiko Tsuchida