“One day, a classmate saw my name is Lily Oki and she was surprised she says, ‘You know I asked my mother, you disappeared you didn’t come back to class to school.’ And someone remembered me all those years? I thought my gosh, it was touching but she said I guess no one talked about it.”

— Lily Yuri Tsurumaki

I would not have met Lily had it not been for the wonders of social media. Her granddaughter, Adina Mori-Holt, who works for the Little Tokyo Service Center in Los Angeles on the forthcoming Terasaki Budokan, reached out to me on Instagram with a simple request: “My grandma always brings stories up from camp but it’s usually while I’m driving. I would love to have an oral history from her before she’s gone.” Of course, I knew the feeling all too well.

Thus launched a nearly two and a half hour interview with Adina and 85-year-old Lily Yuri Tsurumaki, who was born and raised in Los Angeles and still living close to the area where she grew up. Her mother was Nisei and her father, Issei. After meeting in Japan, they essentially got engaged there. But after her father came back to California to start working, her young mother decided to board a ship and make the arduous trip across to California to find him, at only 15 or 16 years old. They managed to make a living in Los Angeles as a domestic and as a gardener, but in 1942 the family of four – which now included Lily and her brother younger brother, Kazuto – would be uprooted from their lives and sent to Heart Mountain.

Lily herself was forced to grow up quickly, adapting to becoming a wife right after the war. “I got married when I was a teen. Everybody else was going dancing, all having their fun.” It would take years of being in a difficult marriage before she decided to strike out on her own with (and for) her young daughter and start a career. She worked for Japan Airlines for twenty years, landing the job in a way that could only be labeled as fate.

In many ways, Lily’s life story is a beautiful tapestry of both good and bad luck: If she didn’t get the job at Japan Airlines, she may have never crossed paths with the man she would call the “single love of my life,” who she would only get to spend a short time with after years in an unsatisfying marriage. It’s a blend of unexplainable, serendipitous encounters and tragic losses. I suppose the same could be said of any of our lives.

Lily begins her story by telling me that her father had a job taking care of the royal family’s horses on Etajima in Hiroshima Bay.

Your father took care of the royal family’s horses?

Yeah, whenever the prince came down to Etajima, that little island? That’s where I guess they kept the horses. But he didn’t like their arrogance or something. Well he did something not too nice. He got scolded.

So he didn’t want to do that work anymore.

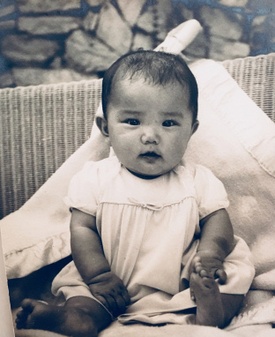

Oh, that was the last picture before we went to camp. That was my mother, my brother, he’s two years younger than me, and my father. The war started what, December 7th wasn’t it? We had our Christmas tree and my dad said we would take the last family picture before–he had to turn in all the cameras, swords and everything into the police station. And he was developing his own pictures at home in the bathtub. He would do it in the bathroom, a dark room.

That’s incredible. So you knew. So December 7th had already happened?

Yeah.

This changes a lot, just looking at the photo that way.

So I was in the third grade down at the at the school down below, down the hill. And in third grade, I had to leave for camp, internment camp. And it was interesting. It wasn’t until we came back and we were finished with high school, there was a high school event, you know they used to have a gathering. And one day, she [a classmate] saw my name is Lily Oki and she was surprised she says, ‘You know I asked my mother, you disappeared you didn’t come back to class to school.’ And someone remembered me all those years? I thought my gosh, it was touching but she said I guess no one talked about it.

So you just left and the teachers didn’t explain.

Just didn’t say anything. She remembered my name is Lily Oki. She came over to me and I thought for someone to remember you, she said she wondered what happened, I just disappeared, I didn’t come to school anymore. I guess no one talked about it. So I thought everybody went to camp somewhere but I found out it’s just the West Coast.

Yes, and all the way up to Washington.

So I thought everybody on the East Coast went to camp is what I thought.

But you knew it was just Japanese people?

Yeah at that age I knew it was just the Japanese because of the war. Well, I know when we came back going to school, a lot of people used to say ‘Hey Jap, get back home,’ or ‘We don’t want you here,’ kind of thing, you know? So I used to go home on a hillside, you know finding hiding places to go back on because you were scared. They would throw rocks or do things you know. I mean they were all kids, your classmates so-to-speak or your same school age. So I guess we weren’t wanted right away.

We didn’t come back right after the war because we went to Pomona Assembly Center where we all–not everybody, some people went to Santa Anita racetrack.

Yes, that’s where my family went. They were sent all the way down here to Santa Anita. But you were in Pomona.

Yeah we were sent to Pomona. So my mother and brother, we went down to the place where the bus came down by Alvarado and Sixth Street, isn’t it? Yeah Sixth Street, where the lake is.

Adina: It’s called MacArthur Park now.

We went by bus and my father drove his truck, his work truck, and they said he could bring it in and he took my mother’s sewing machine because we could only carry what we had on, that was all we could take with us. So my father took my mother’s sewing machine and some of the goods that we might need. The rest of the stuff we had to put under the house basement, what we could keep.

He was allowed to take his truck into the assembly center?

Yes. He had to sell it. He said he got ten dollars for it. He had to drive it in and then, you can’t keep the car there. So he said he had to sell it for ten dollars. What could we do with a car? I mean, we couldn’t bring it back again. But my mother had her sewing machine so she was able to make curtains for our rooms. Little things like that. And I guess with two kids and my brother. She didn’t do too much sewing for boys things but she made all my clothes.

She was resourceful bringing in her sewing machine.

I guess so, I don’t think everyone had those kinds of things.

No. People were lucky enough to bring a few. I’ve heard of a few people smuggling in a sewing machine but it sounds like that was pretty open for your family, like they were allowed to do that.

We knew Pomona because we used to go to their fairground every year. It was in the parking lot I realized because the Main Street, they had a main street with eucalyptus trees planted. So that’s why I remember, ‘Gee that reminds me of Main Street.’ They must have put fence around it to make it into a temporary camp. So all we had was our little room. They called it an assembly center, I don’t know why.

They were still building all the camps. They were still building them and they didn’t have room yet. And so all those terms sounded very benign.

You know I had a florist friend down below, close to where I live, and she said they went directly to Manzanar. And they helped build the camp.

So if you were going to start at the beginning with this picture almost, can you describe what your parents were doing at the time and what was your life like before the war broke out, and what did your parents do?

Well my mom, she was just a housewife but then she was doing some kind of domestic housecleaning on the hillside over there where we are now. Mrs. Long I know she was an artist, and she worked for her, and she helped her a lot.

And my dad was a gardener. So he came around here because he used to always say Larchmont and I don’t know where it was as a kid you know. But he would say a certain thing, something Larchmont, Larchmont. So he was working down on those fancy homes with front lawns because he’s talking about cutting grass on the front lawn. We don’t have our area too many houses with lawns in the front. So I couldn’t figure it out but then after coming out this way more often because of Adina I realized, ‘Oh this is Larchmont.’ There’s a main street, there’s a little shopping area. So that’s why I thought, ‘Oh this is where he was coming out to do his work because he was talking about cutting front lawn and when I thought, ‘Gee we don’t have laws in our areas front.’

Yes, this is where he was working.

He was working more out this way I guess. He was a gardener and Mother was just a domestic. She worked at a doctor’s home, but otherwise she was home.

And were they were they themselves Issei? Or were they Kibei? Or what generation were your parents?

My father be Issei but my mother be Nisei. She was born in Long Beach. But I guess when she was about three or four, her father was a restaurant cook. When the children was raised to start school, he realized if he doesn’t let them go to a Japanese school or a decent school in Japan you will never be able to marry right or go into the right family, kind of thing. So he took all the family home when she was about three, four. Somewhere very young. So my mother’s side, she had a brother, Setsuo, was he younger or older? He used to live with us all the time so I used to always look at him as Superman. He used to do judo. So he was husky, and he looked tall and big and handsome.

That’s kind of nice.

You know after the war, I guess he went home on the last ship. I guess they said his mother was ill, come home immediately. They must have known that the war was going to begin. And he took the last ship home.

So he was over there during the war but before he was living with you.

He was here. I don’t know how long he was here but I remember making mochi, things like that down on Sunset. But he did judo, so he was a strong man, so I always looked up to him as a superhuman. And then when I went back to Japan to meet him the first time with the family after the war, I worked for Japan Airlines. That was my first job, not my first job I guess I was painting ties when I was in high school. But it was a real job that, you know. Oh what happened?

Adina brings out more photos.

After I had gotten married, I know that man [in a photo], Clarence. He left home, so I thought if I didn’t get a job I can’t feed my child, she was only two years old. So I found a nursery school nearby and this was in Highland Park where we were living.

And I went downtown dressed in a suit on a bus. And the store I used to go to was always Broadway because it’s so close to the subway — it used to be subway terminal across the street. So I just went down to the store there and just applied for some kind of job. And they said they liked the way I was dressed, I guess I just had my suit on and they gave me fashion work right away, so I started working. And then I was working in the window.

You know the department stores used to have display windows, corner windows? And they had to do something special on a corner window because Broadway was down on Fourth Street and Seventh Street was Broadway. And 8th Street was May Company in those days and they all sort of competed, which I didn’t know but once I got in there I found out.

So you helped design window display?

I had to actually display them and I don’t know why but I wanted to do kimono. That fall, Christmas, I guess, I couldn’t get any kimonos. I called the dance teacher. I thought they would have all the kimonos and found out they were so expensive and they said the light on it would fade it and all kinds of things. And I thought my gosh I don’t have any kimono.

And then I thought I’ve heard of Japan Airlines down the block. I guess it was Fifth Street. And so I just called them to ask if they have advertisements of hostesses or stewardesses in kimono. So I asked if I could borrow a kimono and I don’t know why, he said he liked my telephone voice. And there was a Clark Hotel right next door to my Broadway department store downstairs at that time, he’d said he’ll meet me there and I’ve never been in a bar in my whole life and I thought, ‘What kind of man is he?’ No, I shouldn’t do this [laughs].

Who’s trying to meet me at a bar by hearing me on the phone? Wow.

It was funny how he said he’d like to meet me and it’s funny how one thing led to another and he wanted to offer me–have me come to Japan Airlines and me take care of their PBX, they had their switchboard. And I was doing that in my senior years.

It’s so funny, my father worked for Japan Airlines. But in the Bay Area. So in San Francisco.

We were off station because our flights didn’t come into L.A. So we had to send everybody up to San Francisco.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku.com on May 13, 2018.

© 2018 Emiko Tsuchida