Historical Context:

At the time of Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, of the roughly 127,000 mainland Japanese American population, two-thirds of them US citizens, the overwhelming majority lived in the three West Coast states of California, Oregon, and Washington, with approximately 94,000 of them California residents.

Colorado’s prewar population of some four thousand Japanese Americans, or Nikkei, was the largest such population among non-Pacific Coast states, though only seven hundred lived in Denver. There, a several-block transitional area along Larimer Street formed a “Japantown” of sorts. This situation in Denver changed quite dramatically, however, within a few months after the US declared war upon Japan in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Following the issuance of Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin Roosevelt empowering military commanders to designate “military areas” as “exclusion zones” from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” A series of subsequent developments, taken together, transformed Denver into the temporary capital of Japanese America. The first of these was the decision by Lieutenant John L. DeWitt, the commander of the Western Defense Command, to exclude all people of Japanese ancestry-Japan-born Issei aliens ineligible for American naturalization and native-born Nisei U.S. citizens alike-from California, the western half of Washington and Oregon, and southern Arizona.

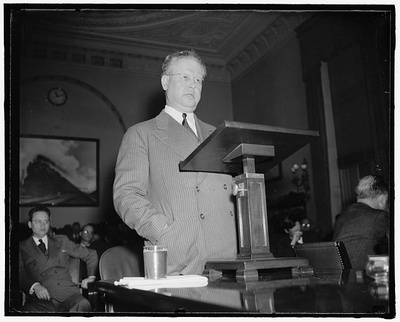

Initially, General DeWitt opted for “voluntary” resettlement, allowing the excluded Nikkei to move to any unrestricted area in the country (of their choosing and at their expense). This policy, which ended on March 27, 1942, resulted in 1,963 Japanese Americans moving to Colorado (the interior state receiving the largest number of Japanese Americans), with a substantial number of them settling in Denver. The main impetus for Japanese American riveting upon Colorado (and particularly Denver) as their destination was that the then Colorado governor, Ralph Carr, was the sole intermountain region governor to welcome Japanese Americans into his state and also to oppose their incarceration.

The policy of the voluntary resettlement was then supplanted by one of involuntary mass expulsion of Japanese Americans from their West Coast homes and neighborhoods, whereby most of the Nikkei were incarcerated first in 17 Wartime Civilian Control Administration-run “assembly centers” in the exclusion zones and then transferred to 10 War Relocation Authority-managed “relocation centers” in the interior West and South regions (one of which was located in southeastern Colorado and called, alternately, “Amache” or “Granada”). Once the populations of these camps had settled in, the War Relocation Authority embarked on a program of “relocation” of the inmates.

Initially, in 1942, those who left the camps did so typically on short-term work leases, mostly as agricultural laborers, but by the summer of 1943, more than ten thousand had relocated out of the camps on a permanent or semi-permanent basis. Because Denver was a metropolitan area (with a wartime population of 325,000) located compatatively near to four of the concentration centers (Amache, Colorado; Heart Mountain, Wyoming; Minidoka, Idaho; and Topaz, Utah), it proved to be an attractive place for Nikkei resettlers seeking employment and housing. As a result, Denver’s wartime Japanese American population peaked at five thousand, even though the War Relocation Authority clamped a 1943 moratorium on resettlement there. Soon the Larimer Street district metamorphosed into a full-blown Little Tokyo, with business, service, and pleasure establishments, along with hotels and family dwellings, lining both sides of the street in a mushrooming ethnic community.

Moreover, this community was served by two of the only four Japanese American vernaculars in existence during World War II. Indeed, World War II and postwar resettlement Denver became the permanent home and workplace for a complement of outstanding Nisei Journalists, among whom were James Omura and Roy Takeno of the Rocky Shimpo, Minoru Yasui of the Colorado Times, and Bill Hosokawa and Larry Tajiri of the Denver Post.

Once World War II ended, the bulk of the wartime population of Denver returned to their prewar West Coast homes or chose to reside elsewhere in the United States. But enough remained in Denver to constitute a viable and vibrant Nikkei community, which still is in existence today. In addition to the living members of that community, there exists presently in Denver, notwithstanding decades of redevelopment that leveled the great majority of wartime and resettlement commercial and residential structures, a number of reminders of what Japanese American Denver was once like during its zenith. There have been some particularly painful losses, however, such as occurred in 1984 with the implosion of the Cosmopolitan Hotel, which in 1946 had been the site of the first post-World War II Japanese American Citizens League biennial convention. It was there where the featured banquet speaker, former governor of the State of Colorado, Ralph Carr, was given a thunderous standing ovation by his JACL audience. This reaction was precipitated by Governor Carr relating that his wartime stand in support of Japanese Americans had been justified by the performance of the Nikkei during World War II, both on the military and the home fronts.

As you peruse the below array of portals related to the World War II/Resettlement era, and perhaps even access in person their correlated sites, it is hoped that you will derive a palpable feeling for the living past of Japanese American Denver.

* * * * *

Portal 1: Sakura Square – Between 19th/20th Streets and Lawrence/Larimer Streets, Denver, CO

Sakura Square, located in downtown Denver’s historic LoDo District, is the center for the city’s comparatively small yet vital Japanese/Japanese American community. Because Sakura Square (which means Cherry Blossom) is far less sizeable than Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo,” Denverites have coined it “Tiny Tokyo.” Built in 1972 in a neighborhood where Japanese-owned businesses had thrived since World War II days, Sakura Square is the home for the Denver Buddhist Temple, the 20-story Tamai Towers Apartments, the Pacific Mercantile Company Asian-inspired market, a Japanese restaurant, a newspaper office, a bookstore, and several other retail shops and business offices.

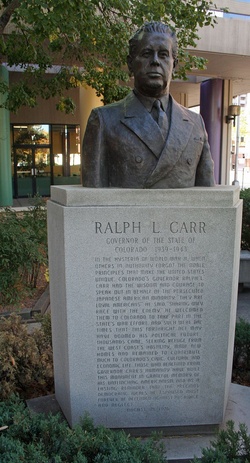

In a garden within the Square there are three historical public markers, each consisting of the bust of key male community benefactor mounted upon a stone base depicting his respective achievements. The first is dedicated to Reverend Yoshitaka Tamai (1900-1983), an immigrant-generation Issei widely known as “the gentle priest,” who touched the lives of thousands while devoting 53 years to meeting the spiritual, cultural, and social needs of his followers in eight Western states. The second marker commemorates the life and deeds of Minoru Yasui (1916-1986), a US citizen-generation Nisei, who was a long-time Denver attorney, civil rights activist, and community leader, who served a year in jail for challenging the federal curfew order for Japanese Americans during World War II and then spent the final years of his life as one of the leaders of the Japanese American Redress Movement. The last of the three markers celebrates the courage of a principled politician, Colorado Republican Governor Ralph Lawrence Carr, the only elected official in the US to publicly apologize to Japanese Americans for their World War II incarceration, as well as the sole intermountain governor to welcome them into his state during this racial-ethnic minority group’s difficult ordeal of persecution.

Portal 2: Pacific Mercantile Company – 1925 Lawrence Street, Denver CO; (303) 295-0293

Founded in 1944 by George Inai, this third-generation Japanese American business, originally named Japan Mercantile Company, is a community landmark located in Sakura Square next to the Denver Buddhist Temple. It imports a wide variety of Asian grocery items. Considered by many to be un-Denver like because lit looks and feels like something one would find in San Francisco or in Seattle’s Pike Street market, it is arguably the best store of its sort in the Greater Denver region. Aside from its affordable prices and wide selection of merchandise, Pacific Mercantile Company is the type of place that is just plain fun for exploring.

Portal 3: 20th Street Café – 1123 20th Street, Denver CO: (303) 295-9041

This café was opened in 1946 by a newly released inmate from a World War II concentration camp, Harry Okubo, in what was then known in Denver as Japanese Town. Now run by Okuno’s grandson and wife, it is located on the periphery of Sakura Square in the LoDo District on the street whose name it sports (and in an area threatened with redevelopment).

Described by some diners as a “dying breed” eatery in that is serves respectable food at a cheap price, the 20th Street Café has been likened to an establishment with a nostalgic ambience evocative of an Edward Hopper painting. With a menu compounded by mainstream American (chicken fried steak, meat loaf, hamburgers) and Japanese American dishes (Hawaiian-like moco loco, fried rice with smoky bacon and fluffy eggs), this vintage restaurant also features a series of rotating specials (roast port, green chili, chicken noodle bowl), familiar sandwiches for the kids (peanut butter and jelly on white bread), and a couple of hearty desserts (a Fat Boy ice cream sandwich and a wedge of pie).

Portal 4: Tri-State/Denver Buddhist Temple – 1947 Lawrence Street, Denver CO: (303) 295-1844

One of four temples that comprise the Mountain States District, the Tri-State/Denver Buddhist Temple is the parent temple of Colorado, as well as the temples in seven surrounding states. Belonging to the Buddhist Churches of America, it is a Jodo Shinshu temple, befitting a community whose immigrant population originated from areas in Japan where Jodo Shinshu Buddhism was strong. These Issei immigrants settled in and around Denver in the early 1900s, and by 1916 the headquarters of the Tri-State Buddhist Church (as it was called upon incorporation) was formed. It was first located at 1942 Market Street in a structure that was previously served as a brothel.

The large infusion of Japanese Americans into Colorado during World War II, first as so-called “voluntary evacuees” from the West Coast defense zones and then as resettlers from the War Relocation Authority-administered “relocation camps” (particularly the one located in southeastern Colorado, Amache) first led to the enlargement of the Denver Buddhist Church facility and then, in 1947, the dedication of a new building, bearing the name of the Tri-State Buddhist Church. This church did not become a separate entity until 1965, and then in 1981 it became known as the Denver Buddhist Temple. In 2002 the Denver Buddhist Temple was involved in a merger that led it to assume its current designation of Tri-State/Denver Buddhist Temple.

Portal 5: Colorado State Archives – 1313 Sherman Street, Room 1B20, Denver CO: (303) 866-2358

The Colorado State Archives provides an exemplary library of genealogy records, and also boasts, among many other historical collections, the records documenting the “Japanese Internment Camp at Granada, Colorado.” In addition, within the Achieves’ “Colorado Governors” collection can be found 54 cubic feet of material related to Ralph Lawrence Carr, Colorado’s governor from 1939 to 1943. It is highlighted by documents pertaining to World War II and the treatment of Japanese Americans during a time when Carr spoke out in defense of the civil rights of Japanese American citizens (arguing that it was both inhumane and unconstitutional for the US government to confine them in concentration camps). The Colorado State Archives public research room is open 9:00 AM to 4:30 PM on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday of each week, excluding holidays, and is closed on weekends and Wednesdays.

Portal 6: Brown Palace Hotel – 321 17th Street, Denver CO: (303) 297-3111

Designed by Frank Edbrooke and completed in 1892, the venerable Brown Palace Hotel features carved sandstone on a base of granite and was the country’s second fireproof building. Over a century later, the Brown Palace, nestled in the middle of downtown, remains one of Denver’s finest hotels. Rich in history and tradition, this elegant hostelry, now surrounded by high-rise buildings, employed a substantial number of Japanese Americans in service jobs during the World War II and Resettlement era.

Portal 7: Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse – 1823 Stout Street, Denver CO

Construction on this building began in 1910, although it did not open for public use until January of 1916 as the US Post Office and Courthouse. Its architects from New York (Tracy, Swartwout, and Litchfield) brought grand Neo-Classical design elements to this Denver building that were already popular in the eastern United States. Its monumental scale and elegance expressed its official and public character and served as an inspiration for other buildings in the city. Occupying an entire city block in downtown Denver and standing four stories in height, it is clad in Colorado Yule marble, the same material used for the Lincoln Memorial and the tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Washington D.C. This 244,000 square-foot building, which underwent extensive renovation in the early 1990s, was renamed and dedicated in 1994 as the Byron R. White US Courthouse, so as to honor a native son of Colorado, Byron “Whizzer” White, who had been an All-American football player and Rhodes Scholar in the late 1930s and was appointed in 1962 by President John Kennedy as a US Supreme Court Justice.

This courthouse, which serves as the home for the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, assumed great significance during World War II for at least two notable actions: first, it was the site of the federal court trial in 1944 in which 3 Japanese American sisters were convicted of conspiracy to commit treason for helping 2 German prisoners-of-war escape from a Colorado POW camp; and second, it was the setting for the decision in December 1945 by the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals to overturn the November 1944 conviction of 7 leaders of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee by the Federal Circuit Court in Cheyenne, Wyoming, for their alleged conspiracy to counsel draft resistance.

* This article was originally published within the program for the JANM-sponsored national conference “Whose America, Who’s American: Diversity, Civil Liberties, and Social Justice,” held in Denver, Colorado, July 3-6, 2008. The conference was a component of the multi-state project, Enduring Communities: Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah.

© 2008 Arthur Hansen