Basil had just graduated from kindergarten when the uprooting and internment started. His father was initially sent with the other able-bodied young men to work on a road camp while Basil and his mother were sent directly from Vancouver to the Slocan City internment camp in eastern BC. He clearly remembers getting on the train to go to the internment camp. It was his first train trip, so it was exciting for him, but he had no idea of why they were getting on the train or where they were going.

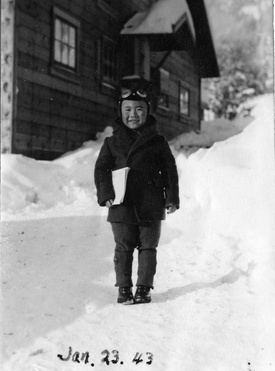

Their lodgings at the Slocan City camp were not yet ready, so at first they had to sleep in a tent. Basil, who had never seen snow before, recalls his amazement at waking up on the first morning in Slocan City, going outside the tent and finding his surroundings “white with snow”. After that they lived for a while in a hotel room that was “kind of bare and stark.” They didn’t stay there very long and moved again soon after his father came from the road construction camp and joined them.

Cameras were among the property items that the government had confiscated from Japanese Canadians before the internment, and they were also officially banned from the camps. However, as time passed some of the officials in charge of the camps tended to become lax in enforcing these rules and turned a blind eye to some minor infractions, including the possession of cameras and taking photos.1 Mr. Campbell, the photography shop owner who had trained and employed Basil’s father in Vancouver, brought Basil’s father’s cameras to the camp and gave them to him.

Basil’s father wanted to move around and record life in the various camps with his cameras, and it seems he was able to receive official permission to do so, so over the remainder of the internment period the Izumi family moved from camp to camp. Due to more and more people leaving the camps to move east of BC, it was not difficult to find lodgings and move between the various camps.

First, the Izumi family moved to the camp at New Denver where they lived in a little shack and stayed just long enough for Basil to start attending the school there. Next, they moved to the nearby Nelson Ranch camp where they lived in a huge two-story bunkhouse for about half a year. They ate together with everyone else in a mess hall, and as far as Basil recalls, his mother did not need to do any cooking there.

During this time he continued to walk to the same school he had attended while in New Denver. The long walk seemed normal to him, and he remembers chasing squirrels along the way.

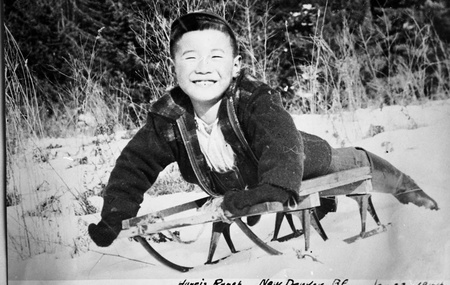

Then they moved to the Harris Ranch camp, where they lived in a shack at the top of the hill. They stayed there for about one and a half to two years. Basil remembers noticing that the walk to and from school was longer than when he lived in Nelson Ranch.

Then they went to Lemon Creek, but that was only for a short time as well, during the summer months.Their last stay was at the Bay Farm camp, which was located next to the Slocan City camp where they had first arrived in 1942.

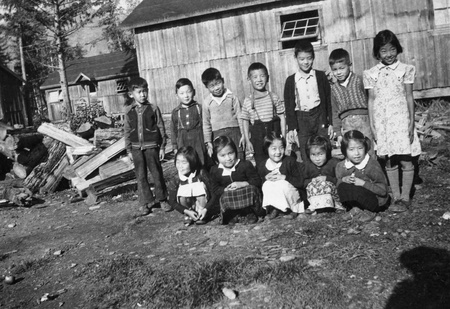

Memories of Childhood Play in the Camps

Like many other Japanese Canadian children who were in the camps, Basil’s memories of this period are very positive and mostly revolve around enjoying school and nature and playing with his friends. His most vivid memory is about an incident with his father:

“Summer was hot, so everyone used to go to the Slocan River to swim. I followed my Dad to the river one time. There was a nice wide area where the current was very slow so you could swim across. You could see guys jumping off the cliff into the river on the other side, and I wanted to do that too. So, I tried to swim across. My father saw me following him and got mad and told me to go back. So, I swam back. I was being carried downstream toward the rapids but somehow made it across to the other side ok.”

He also recalls that he and his friends used to devise and improvise many games in order to amuse themselves. One of the most popular games was called ‘Aunty-Aunty,’ in which two teams would stand on opposite sides of a building and throw a ball over the roof. First, one team would shout ‘Aunty Aunty’ and throw the ball over. The team on the receiving side would catch the ball and run around to the other side and try to tag or hit an opposing member with the ball. The tagged person would then have to join their team. The team with the most members at the end was the winner.

Another game resembled cricket. They would stand up three sticks at each end of the playing area. Then they would throw the ball toward the sticks of the opposing team, and a batter with a regular baseball bat would try to hit the ball away in order to keep it from hitting the sticks. If you could hit the other team’s sticks with the ball you would score.

He also recalls watching older kids playing baseball, and playing it himself a little bit. Those who had ice skates would skate when the water froze over. The area around Harris Ranch especially had nice hills for skiing and sleighing. He remembers making homemade skis from the slats of wooden barrels. They even made sleighs, and joined two sleighs together to form a bobsled. They improvised like this in order to make a lot of the toys that they played with.

Generally, Basil had a good time as a child in the camps. He does not recall his parents revealing any grief or anguish to him during this time, although he adds, “If they did, it was way over my head”.

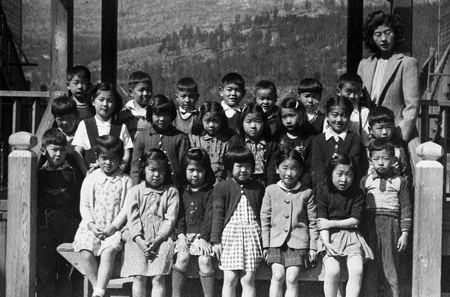

Memories of school in the camps

He likewise has some interesting memories of attending elementary school in the camps. There was a Japanese Canadian lady who was the main teacher, and she trained Japanese Canadians who were already high school graduates to teach elementary school students. School was a lot of fun.

Basil has one particularly vivid memory about the Bay Farm elementary school, a two-story building. While Basil’s class was studying in the classroom upstairs, there was a fire in the home economics classroom downstairs, so they “had a real fire drill”. Fortunately, they were able to put it out before it caused major damage.

Basil thinks the teachers in the camps did very well under extremely difficult circumstances.2 They did not have enough materials, and the textbooks they did have were very old. He remembers using the ‘Dick and Jane’ reading textbooks that were common at that time3.

Basil has no memories of personal racial discrimination during the internment as the internees had little contact with outsiders. Slocan city had its own school system, but the Japanese Canadian kids were not allowed to enroll, so they only attended the schools set up for them inside the camps.

Notes:

1. Kunimoto (2004), 135-6 describes some possible reasons for this.

2. Moritsugu (2001) contains numerous testimonials from students and teachers about the hardships and the good memories regarding the schools in the internment camps, and how well the teachers did in spite of their challenging circumstances.

3. Coincidentally, the writer also remembers reading the Dick and Jane reading textbooks in elementary school (in rural Alberta) in the mid 1960s, so they obviously were commonly used for many years in Canadian elementary education.

* This series is an abridged version of the original article titled, “A Japanese Canadian Child-Exile: The Life History of Basil Izumi,” originally published in The Journal of the Institute for Language and Culture, Konan University, Vol. 22, pp. 71-108 (March 2018).

© 2018 Stanley Kirk