And where did your family end up after the war? How did you come to Philadelphia?

So this is interesting, too. My parents had just gotten married and they had all their wedding stuff and they were renting a house. And their landlord said, ‘Well, you can store it here and this place will be available when you come back.’

Oh wow, so they were lucky.

They were lucky. And my dad had a job because his brother-in-law still had his pottery, so my dad worked in the pottery and became a supervisor there. So they came back to Auburn, Washington and I grew up there. And I came out here because there was a job.

But a lot of the Japanese Americans that are in Philadelphia, some came from Seabrook because that was a place they recruited workers but also the Quakers. They were very helpful, they got places for the Nikkei who were qualified to go to college, they got them into colleges. And a very good friend of mine worked for the American Friends Service Committee, so the Friends did a lot to try to help the Japanese Americans. There were Nikkei who were from here, originally and so their story is different because they never sent into camp.

Yes, those perspectives are interesting, people who grew up on the East Coast. I spoke to someone who was an MIS vet who thought he was more Italian than Japanese growing up.

Well they weren’t a critical mass, they weren’t a threat. Both of my parents were Nisei and my mother grew up in a small town north of Seattle in Burlington, Washington. They were one of three Japanese families that lived in that area. But they assimilated into the community because they weren’t a critical mass, they weren’t a threat. And it’s really interesting because when I was doing research, I found out that a young woman from that area was doing a doctorate thesis on the three Japanese families living there, and they were all middle class.

My grandparents owned a dry cleaning business, another family the father was a photographer and I think the third family was in nursery, growing plants. So because a lot of the people had died, she got the local newspapers at that time and found out how they had integrated. There were things like, they went to the bridal shower, my uncle was in the band, my other uncle was class president. So they all kind of fit in that community. So because they’re not a threat, they’re thought of as, ‘Okay, a person with a different background.’

On the West Coast it was so different because of the economic threat they posed.

Because they were so successful. It was so economic. In Idaho in particular, the governor was really racist against Nikkei. And he was one who first suggested concentration camps. But then, when the Amalgamated Sugar Company said, ‘we need workers,’ he changed his mind. So in this day in age you can understand, it’s the same with Muslims. People just have this stereotype, people just think of them in one way as terrorists. And we were all spies.

During the exhibit, there were several Nikkei who came so instead of me talking, I asked what their experiences were. So one woman brought her family to the exhibit, and her sons were mixed heritage, and she says she had never told them about it. But she was so grateful for the exhibit because now she could explain it. She said she heard from her family that they had a store or restaurant before camp and of course they lost it all. So when they got out, they had nothing and so a friend said that they could live on their farm and live in a tin shack. Worked night and day, apparently. Finally were able to save enough money to buy a restaurant but she was just in tears about, you know, ‘This is what my family experienced.’ So the stories are just really amazing. The resilience.

And there’s also an assumption that it’s not in the nature of the Japanese community to lament about the past.

I think yes and no. I only knew my grandparents after the war and I remember always whenever I visited them, they always seemed sort of placid. Of course they only spoke Japanese, my grandmother did speak some English. And they belonged to a church but my grandfather always seemed a little depressed. And my mother would talk about how he was this very dominant person in the family and he disciplined them harshly and it never squared with my image of him. But I think he was depressed. He had come to America, he had worked his way through, he had a successful business, and then in a second, it was destroyed. And of course he was probably in his 60s and 70s, so how do you start over? So then you have to rely on your children.

Your sense of agency is gone.

Right. So that’s why I say that I think if you’re young and you see that there’s a future, then you are resilient. And I think that’s what happened to a lot of the Issei.

So emotionally, do you feel like this ever affected your parents?

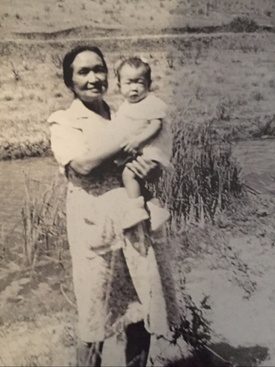

They got on with life. My father was very industrious, he had a big personality. He grew up in Pendleton, Oregon. And I don’t know, I never really asked him, but he was able to bridge community so he felt comfortable in the white community as well as the Japanese community. His mother died at childbirth with his younger sister so he was kind of brought up by his elder sister who was born in Japan. I don’t know how much that affected his sense of how much he had a stake in the family. But I think in that day in age, Japanese Americans pretty much stayed together.

My mother on the other hand because she lived in this community and they assimilated very well, we never had any problems. She never felt uncomfortable having white friends. We probably had as many white friends as we did Nikkei friends. And I grew up in a small town so it wasn’t like Seattle. Because in Seattle, much like San Francisco or L.A., you get into that enclave and you’re part of that.

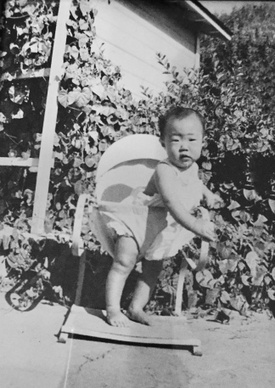

I think in my graduating class of 300, there were maybe six of us Nikkei. So I never felt that I didn’t belong. I shouldn’t say that. I did feel that at times, especially in adolescence and I heard racist comments, too. So I knew I was different but it didn’t prevent our family from being successful. There were five of us and we did very well. My father at one point was Father of the Year and my mother when she turned 80, they have this contest called Pioneer Queen and she won Pioneer Queen. She was the first Japanese American Pioneer Queen.

Sounds like they were very respected and well-liked.

I’ve had reunions with my classmates and one of my friends I was telling, ‘You know, I never really felt a lot of prejudice.’ And he said to me, ‘Well that’s because we protected you.’ So, you wonder how much was said that I didn’t hear.

And you mentioned that you felt you had this consciousness later of looking at the history. Was there something that changed?

Well, I’m a product of the sixties so at that time, movements started with Black awareness. I think at the same time, Asians started to find out more because we never learned about this in school. So when I came here to Philadelphia and I joined the JACL, as I said this is really an activist chapter. So I learned a lot about it. I also was chapter president and was on the national board. And I was appointed Education Chair because I’m a teacher. I think once I became active here I was much more involved.

It just really fascinated me that I could be 70 years old and not know all this that happened. What my parents experienced, why the government did this. Why did people leave the camps to go work in the fields? It’s just fascinating.

So you said your mother went back to Caldwell. What was her reaction?

Well it’s interesting. It was 2014 that we went and she was ill. She had been suffering for several years from sciatica. So she was in pain and when we took the trip she wasn’t feeling well and I didn’t know the extent of it. So we went in August, she died in October. I think she was glad that I was trying to discover, and that it was interesting to me. Because to her it wasn’t interesting. That’s a part of her life that she wants to forget.

And so, we went to see Mike and we talked about it and he asked her what she remembered. And there were curious things. One of the things she did say was that when my dad was out working, they had a car. I don’t understand how they had a car but she went into town, and she said she remembered the ‘No Japs’ signs. So there were places they couldn’t go, they were always confronted with this.

So I think that generation isn’t like our generation that grew up with the thought that we’re all equal. I think they understood it but they also knew that their parents were immigrants, and so they weren’t quite up to par, so to speak. And then of course what happened with Pearl Harbor then just destroyed their lives. And they would forever be associated as the enemy. So I’ve always had a little tinge when December 7th came but I didn’t experience like they experienced it.

She’d always talk about the Japanese saying shikata ga nai and gaman. And I think they truly lived that. Life is not easy, and certainly they didn’t have it like you or I, we live in a fairly comfortable time. They didn’t. They knew they had to work hard, they knew they’d always be discriminated against. I think it was that feeling that you have to get on with life and make the most of what you have. And stop feeling sorry for yourself. [laughs]

I often have that similar conversation with people that we can’t take what they went through for granted. Not that they didn’t have their own fun or enjoy life, but the sense of security we have is something they didn’t.

Our generation, really our parents, did become successful and did enjoy that. So we’re standing on the shoulders obviously. I don’t think any of us feel it could be snatched away immediately like that, but I think our generation feels that you can plan, and you try to do this and that. But we had something to start from.

A warm thank you to Rob Buscher of the Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival for coordinating this interview.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on February 3, 2018.

© 2018 Emiko Tsuchida