The Fife History Museum is a converted midcentury home, awaiting its next stage of storytelling—but it’s a place filled with objects waiting to speak.

“I had no idea just how big the Japanese community of Fife-Auburn-Kent was until I began working for the historical society,” says Julie Watts, the museum’s director. “I look at our Japanese artifacts and files and think, ‘I have got to figure out how to transform what we have into compelling, emotional stories that will enlighten the minds of our citizens and visitors.’”

Fife is a small town in Washington State—with a little less than 10,000 residents—not far from Seattle and next to my hometown, Tacoma. It lies entirely within the Puyallup reservation, and is rich with a cross-cultural history of the Puyallup, Scandinavian, Swiss, German, Polish, and Japanese Americans. It did not become incorporated in 1957, but both Shunichi Otsuka’s History of the Japanese in Tacoma and Ronald Magden’s book Furusato discuss the history of Japanese Americans in the early part of the 20th century, with a great deal of people, agricultural goods, and commerce flowing between Fife and Tacoma. Japanese American farmers cultivated the soil of the valley, selling their produce in Tacoma and the Seattle area.

Formed in 2000, the Fife Historical Society and its connected museum is also a relatively new creation, and with a fair amount of leadership turnover in the last several years, the museum itself is in a state of transition. Watts is the museum’s only paid staff member, though she also works with a board of community members. The museum is the former home of the Dacca family, and Judge Frank Dacca sits on the board of the museum.

Watts, who grew up in the Fife area, is determined to persevere despite a less-than-ideal staffing and resource situation. Trying to capture the interest of local residents, fulfilling the museum’s mission of “building community through history,” she issued a survey in 2017. “Out of 14 topics presented in the survey,” she says, “the top three most selected historical topics that respondents said they would most like to learn about, were the settlers that immigrated here, the WWII internment of our Japanese citizens, and the Puyallup tribe.” So the desire and the audience are there. But Watts needs more: skilled volunteers to assist with interpretation of the materials that the Museum has, and to create exhibits that will help these objects to speak.

* * * * *

To show me a sample of the museum’s Japanese American-related artifacts, Watts takes me downstairs to the basement of the museum. There are two American flags there, both folded properly into stern ceremonial triangles. One is faded, slightly worn; the other is enclosed in a glass case with a small brass plaque.

After my visit, Watts sends me a link to With Honors Denied, a brief documentary made by Mimi Gan about a Japanese American woman from Fife. According to the film, the first flag was a gift to Fife High School from the 22 Japanese Americans who were supposed to graduate high school in 1942; one out of three students graduating were Nikkei. The Nisei were forcibly removed five miles away to “Camp Harmony” in nearby Puyallup. Though the school did not give the students a graduation ceremony before they left, they did give the students a special day. On that day its class vice president, Yuki Kubo Shiogi, collected money for the flag, and presented it to the school. Her classmate, George Morihiro, recalled that Yuki presented the flag, and began to cry—indeed, “everyone was crying, or had tears in their eyes.” “I remember collecting money for the flag,” Yuki said later, “but I don’t remember that actual day.” She received her diploma behind barbed wire in Puyallup—and although she returned to Fife, she did not return to the school itself for decades.

The second American flag, the one in its glass case, has its own related story to tell. Sixty years later, Yuki Shiogi finally stood in a blue Fife High School graduation gown with other Nisei who had been denied their diplomas. Once again, she spoke on behalf of her classmates. “Japanese Americans, class of 1942, would like to present the class of 2002 and Fife High School an American flag [pause] to show our appreciation for the graciousness in permitting us to join them in their big day.”

Both flags now sit next to each other in the Fife History Museum, next to high school yearbooks and class portraits of the time. They’re in the same room with old yearbooks, old school desks, school books, a bookshelf of yearbooks.

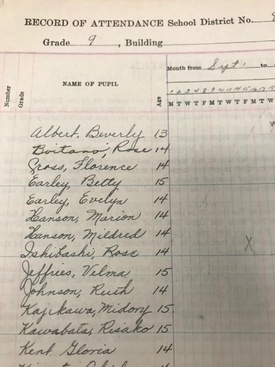

Watts shows me the class photos and yearbooks, class registers with so many Japanese names. “When I show visitors the photo of the school district photo from the 1920s, it is so powerful,” she says. “You see, sitting and standing side by side, an international student body made up of Puyallup tribal children, Swiss children, Italian children, Japanese children, Scandinavian children, and I’m sure a few Germans and Poles in there. And after I show them that photo, I direct their attention to a 3rd grade class from 1943 and say, “Where are all of the Japanese children? How do you think this generation grew up thinking about their Japanese classmates, as opposed to the students in the photo from the 1920s?”

Watts is especially motivated to tell the story of Japanese Americans who were forcibly removed from the area. “[There’s] a reaction that people have when they hear about it for the first time,” she says. “Everyone is moved. It’s almost like there is an immediate shift in their thinking, when it sinks in that hundreds of local, innocent families, grandpas and grandmas and parents and children and neighbors…were forced to leave everything they had worked for, on such short notice, under harsh conditions, and without justice afterwards. There are eerily similar sentiments being made about other peoples today and it scares me that I can see conditions that brought that injustice about, brewing again in America.”

Near the front door of the museum, there are several handmade Japanese objects. There is a tree made out of small paper parasols stands near the front door of the museum. Mary Ikeda made it while she were incarcerated—and it is made almost entirely out of toothpicks and cigarette papers. There are pieces of shell artwork, flowers made from shells by Mrs. T. Hoshide and Mrs. Yaeko Nakano during their time at Minidoka. There are handmade Japanese dolls by Mrs. Sadao Yotsuuye. These objects are beautiful, but knowing their origin stories can only enhance their beauty.

* * * * *

There are many stories which include Fife’s Japanese Americans, such as the museum’s exhibit on veterans. But there are many more Nikkei stories which can and should be told. Museum board member Mizu Sugimura, a local Nikkei artist, tells me that shortly after moving to Fife six years ago, she learned about Fife’s historic (and no longer extant) Japanese Language School. Former Japanese language school student Cho Shimizu talks about some of this Fife history in his memoir, Cho’s Story. Members of the Puyallup tribe leased land to Japanese American farmers. Historian Michael Sullivan tells one such story about the Fife community on his public history blog, Tacoma History. Both Michael and Mizu speak passionately about the story of Irish immigrant John McAleer, who left his 65-acre Fife ranch to his Japanese immigrant employee, Kay Yamamoto—a story which carries its own courtroom drama. And there is much more to say about Bob Mizukami, who served in the 442nd regiment during World War II, served as the city’s first police commissioner, and became the city’s first Japanese American mayor. And there are stories that local Japanese Americans have told about the acts of generosity and kindness that they received from their neighbors when they returned from the concentration camps.

The stories of other Fife residents, including Cho Shimizu and Elsie Yotsuuye Taniguchi are told in the Puyallup Valley JACL documentary, The Silent Fair. Overall, the Japanese American community history as it intertwines with the local farmers and the Puyallup Tribe also deserves more attention.

The museum’s journey, in some ways, has just begun. Nevertheless, “I deeply believe in the goodness of people,” says Watts. “If they have access to stories of wisdom, they will not make the mistake of acting out in fear.”

© 2018 Tamiko Nimura