Going back into Manzanar again, was there one person that gave you that nickname “the songbird”?

I don’t know who gave me that nickname, but I kind of think it could have been the music director of the camp, Louie Frizzell. He took me under his wing and he used to go out into the camp on the days when he didn’t have to teach and bring brand new sheet music for me to learn; new songs of the day, the current songs. You know things like Judy Garland or Doris Day or whoever was popular and he would bring back new sheet music for me to learn and teach it to me and accompany me in all programs we had at camp. So I always considered him my mentor, he kept me current.

He’s like, here are the contemporary songs.

Yeah I could sing contemporary songs. “Meet Me in St. Louis” by Judy Garland and things like that.

What were some of your favorite songs to sing? Are there any that you think of that define that time for you?

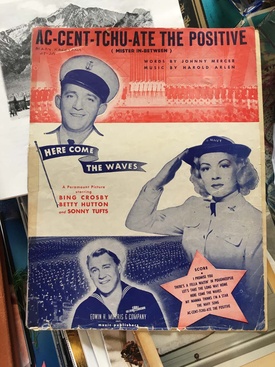

The up tempo ones that I really like to sing are “Accentuate the Positive.” “Night and Day” and “Old Black Magic.”

When you were in Manzanar what was your state of mind? I mean eventually you there for three almost four years. First it was a shock but then you started making friends. At what point did you feel did you get into some kind of groove?

It was early that I could get into it because it was in April when we were put it in camp in school I was in 11th grade. So I had to go to school and I’ve met so many Japanese, I never knew that there were that many Japanese in the world. So I mean we were best friends right away. And so this time in my life I was beginning to meet people I became lifelong friends with. And I was shy, I didn’t know anything about boys. They meant nothing to me and I just had lots of fun with the girls and played softball with them. Then I started dating with the high school classmates and stuff. Then I got very, um not involved, but he was my best boyfriend and we were going out for quite a while. We had just graduated high school and then he had to go to Crystal City to join his father. So we separated and we kept corresponding back and forth. It was kind of futile because we didn’t know what was going to happen to us. And so I had to give him a Dear John letter. In the meantime I was still entertaining at the camp and the camp programs.

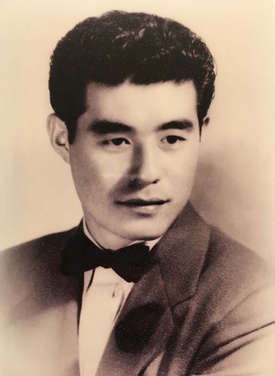

I was asked to sing for the group called the Manzanites, one of the better men’s club in camp with all the good looking men, all the sports guys were in it. They were having their dance and they asked me to entertain. So in those days they always have an intermission to have somebody tap dance or sing. And so the adviser of that club was Shi Nomura and he says, “Does Mary have an escort?”

And in that camp everybody knew who was going around with who, who broke up, who’s getting married all that stuff. They said “No her current boyfriend had to leave camp and there’s another boyfriend after the fellow went to Texas.” He just left for the East Coast to look for a job and we weren’t really, we were separate just dating. He says “Then one of you boys take her.” And they said, “Well we all have dates already.” He said “Well then you boys who don’t have a date, you ask her. You take her so she doesn’t go to a dance by herself that night.” So the guy says, “She’s too tall for us.” I was considered tall in those days. He says, “Well I don’t want that girl coming and singing at night without an escort. I’ll take her this time but next time you make sure that she has somebody to bring her.” His friend came to the office where I was working. He says, “Shi Nomura is going to come pick you up because he doesn’t want you to come by yourself. And so I said, “Oh okay” and so he came to pick me up and I think that was in November, end of November. It was called a turkey trot, it was a camp dance and by New Year’s Eve we were spoken for each other.

Was that first time you met each other was when he came to pick you up to take you to?

He had seen me entertain pre-war days at that Nisei Week talent show. I said “You are a fickle man” because he was with his girlfriend sitting next to him, who he was going to get married to — that’s another long story. He heard me singing, and I was 14 and he says he was smitten. He says, “I’m going to marry that girl.” What an idiot, with his girlfriend next to him. That’s what he said he always remembers saying, “I’m going to marry that girl.” Then heard me singing in camp. He says “That sounds familiar.” He didn’t know me and so then when he took me–

He remembered you by that point, like he knew that was the same person from before.

I said you are a two timing, fast worker.

See and everything worked out how it was supposed to. When you went to dance with him or you were escorted, how was your feeling towards him at the time?

I really didn’t have that romantic feeling towards him but I said, “Oh he’s one of the more handsome — he was one of the handsomest guys in camp.” Very handsome man. It was nice. He was a gentleman and he was very cordial. We had a nice time and he asked me to a New Year’s Eve dance and then I’d never been to New Year’s Eve dance. Then my sister had a bunch of friends that were dating. My sister was three years younger than I, my little sister. And she says “I heard that he kissed you.” I said, “Yeah.”

So that was New Years and he says, “I want to get married and we’re going to get married. We’re going to tell your brother that we’re going to get married. He better agree to it because I’m going to.” I left camp in January. He was still in camp. I went to Pasadena.

This is because of your brother’s job?

Yes. California was opened up for the Japanese to come back so he got a job and I found a job as a housekeeper. While he [Shi] was in camp I made a recording. He’s used to write me love poems, used to write poetry. And I used to set it to music and I took those words and I set it to my own music and took it to a place to get recorded on one of those little records with the big holes in it. I sent it back to him. And so he had that record. And before I left camp, I made a recording with the music teacher on a big 78 disc of I think five of these songs that I recorded. So I think that’s the only recording of an actual music taken in camp of all the ten camps.

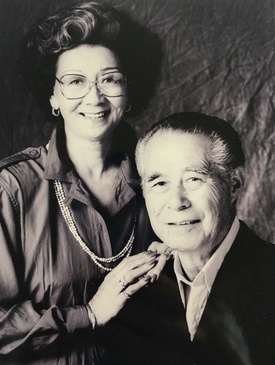

Is it true that your husband said, because this is where I met my wife, Manzanar was kind of a — I don’t know if happy is the right word?

That’s how he always said that Manzanar was a terrible terrible experience for everybody and memory that they won’t forget, but I have to keep the other part the memory of my getting married and meeting my future wife there and having children after that and doing all the dedicated work at the museum. He says “I can only think of the better part of that. I can’t harbored the bad part of that because other people can do it but I’m not.”

He wants to remember the good?

Yes, yes.

When he passed, again I don’t know if Alan [Mary’s son] said this, but did he say your husband say he wanted to be buried out there?

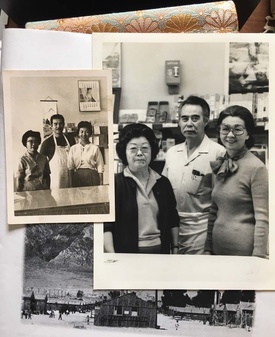

There was no barracks or anything there at the camp, he wanted to construct a barrack replica and make it a home for he and I to live in so he could conduct tours for anyone who came to see the camp to see what it was like. He says, “I want to live there and show people.”Just not me. I’m not going to live away from my children, and my grandchildren were about to come at that time. I said I’m not going to do that. But we did buy property in Independence so we could retire there. There was a three plot mobile home area of what I guess you call a mobile home. The one facing the mountain was the one he bought and we were going to retire there someday. I said well we can go back and forth but I’m not going to live in the barrack. So we did buy it, but he passed. He was still doing work with the museum [in the town of Independence]. So they still call it the Manzanar Project with Shiro Nomura. He said, “If it wasn’t for this, we wouldn’t have met at all”. He lived in L.A. I lived in Venice. We would not have met. So he always said that was a plus, the only thing he could say, it was a plus. And then after that we just went here and there and had kids in between. Five kids. And when I came out of camp I was a housewife, and the only time I went to work was after my children were all born and we started a fish market. We had a fish market for 22 years. Popular and quite successful.

Did anyone take it over after you?

Nobody wanted it except my son-in-law who is Jewish. Nobody wanted the hard work. We kept it so clean and people would come in and go, “How come this doesn’t smell like a fish market?” Because we scrubbed down the floor and everything every night.

What was the name of the fish market?

Shi’s Fish Mart.

Of course it was!

So people would say “Shish Fish.” But then within the last eleven years of his life he developed Alzheimer’s and he forgot a lot of things, he forgot how to say things, even the mid part of it he says, “What’s your name?” to me. He could not remember. He could not remember how to eat, how to pick up utensils to eat. He completely lost all modes of existing.

Thinking about this time right now in this kind of political climate, are you afraid and surprised you’re seeing similar things?

I don’t think the government, the Congress is going to allow it. They will not allow it. I’m hoping so, but I’m pretty sure they won’t allow it. But that big guy is adamant about making that happen because he is so bent on having that wall built. I don’t know what your political affiliation is but I just don’t go for it. But I don’t think Congress will allow it to happen because too many people are so against it in America.

That’s true and the Japanese Americans fought too hard for it. When you received the redress money what was your feeling when you got it? Did it mean something to you or what did that mean to you when you got the apology?

To me, it wasn’t enough. It was a token gesture. It was something that was misused. You know “arigatai,” you know we thought, well that was something. It was a token but how can you put monetary value on what they did to all of us you know? I’m not saying we should have gotten more but it just wasn’t, it wasn’t the right way or the right way to say it for what they did. It just wasn’t right. It didn’t settle my feeling that that’s not enough. Not enough not in a monetary way, but how can you forgive that? So many lives were affected by that. People, mentally and physically and I just I felt that it was OK for some people who really needed that money even because it wasn’t enough. What I thought wasn’t, it was just a token. And I can’t say it should have been three times that amount. But I can’t put the monetary value of that in all of that but I just it just wasn’t it didn’t settle so because “oh great I don’t buy me a car” and just flip it because they’re doing OK. You know there’s some people just struggled and the majority of it got all over it. We did alright. I mean it’s just something that says we’re not down on the ground having people step on us we were just able to get back on our feet and do things, but it’s just the thought of it should not have happened and what they did for us afterwards thinking this is going to be our token apology. It wasn’t. No it wasn’t.

Did it affect your oldest brother in any way?

I shouldn’t say the word blessing but it was a blessing for my brother. He didn’t have to struggle to take care of his three little sisters. He didn’t have to go out and look for money to get money to feed them and pay for rent and all that. So when the government took us and made sure that we had so-called roof over our head and fed us it took that responsibility off of him. And so my sisters and I felt that it was a blessing for him. It made it easier for his life until he met his wife in camp also. So from then on it was easier for him. We don’t know how it would happen, how would we have survived with welfare or whatever to take care of us? In those days it was ,“Oh no, Japanese people don’t use things.” But it was pride that allowed him to take care of us but I don’t know how he would have kept it up.

Well then it’s something again positive, that helped.

Yeah that’s the way we look at it, it helped my brother. He didn’t have to struggle to put food on the table and take care of us.

I understand that you didn’t pursue singing professionally?

I never did. I just sang when I got asked to sing at programs, because I always thought when I was a little girl, I’m going to be a singer on the radio. I always thought I would not get in the movies, because who’s going to see a Japanese girl performing in the movies? So if they hear me singing on a record, they won’t know it’s my Japanese face singing. So I always thought, well I’m going to be a singer and make recordings. That’s what I thought I was going to do.

The fact that you didn’t but you still kept performing, I’m sure you just feel happy that you could still sing in any kind of context.

If somebody asked me to sing, I said, “Well let me know early enough so I can practice.”

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on October 21, 2018.

© 2018 Emiko Tsuchida