You could say it really started with a hallway.

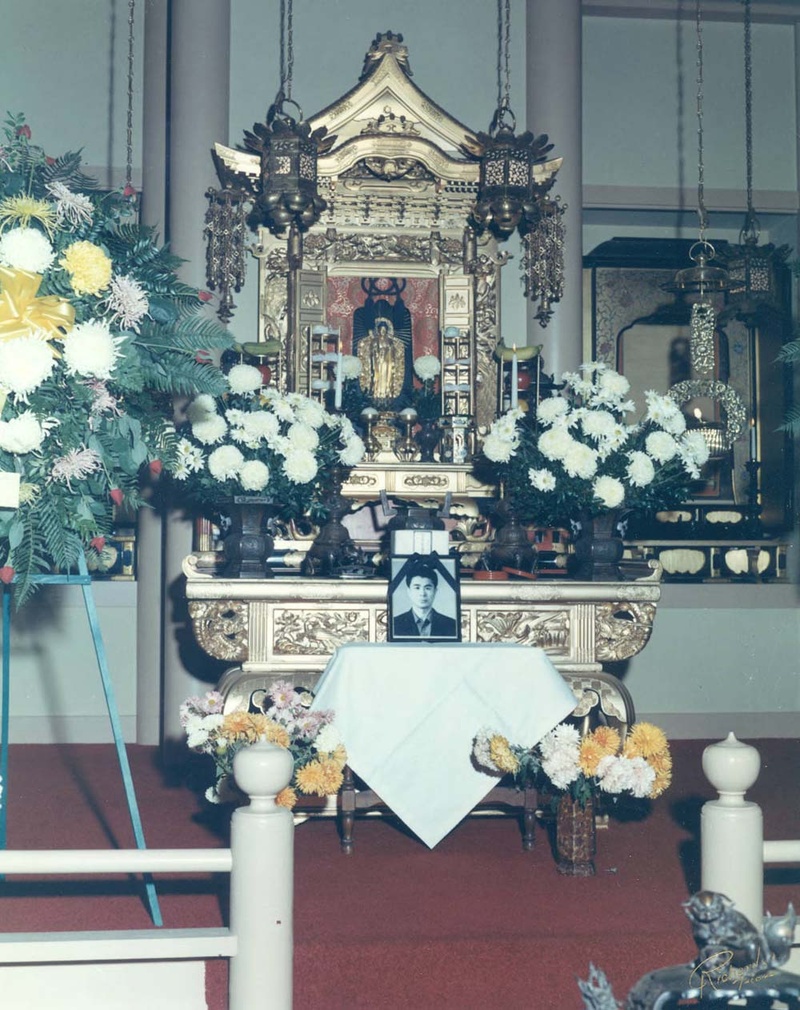

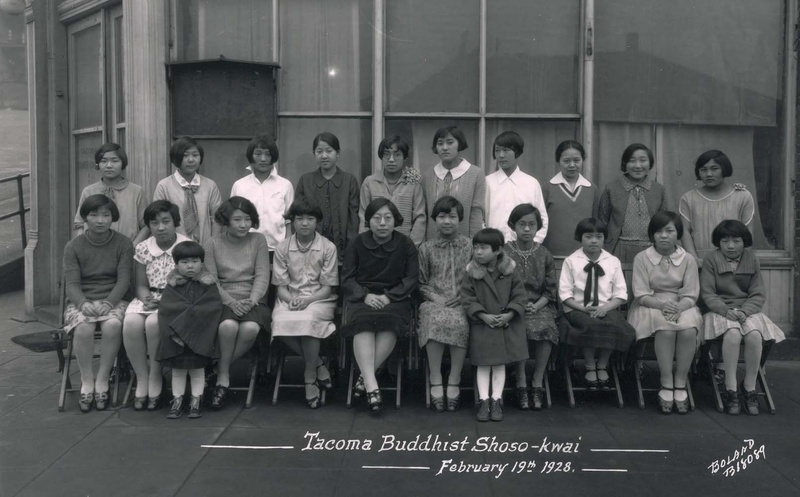

Next to the hondo (shrine) at the Tacoma Buddhist Temple, there’s a narrow hallway filled with framed photographs—sepia, black-and-white, panoramic shots, professional portraits. Many of them are group shots in front of the Temple itself, even in various locations. The hallway can’t be much more than 100, 120 feet long. Wood paneling runs along the bottom half of the walls, white walls along the upper half. Many of the photos are close to 80 years old, if not older. There are pictures of Japanese American youth groups, baseball teams, sangha members at Buddhist conventions.

I had been to the Tacoma Buddhist Temple for public events—Bon Odori, and sukiyaki dinners, and fall fundraisers. I hadn’t been inside that hallway.

For the last year or so my colleague Justin Wadland and I have been writing a short history of the Tacoma Buddhist Temple for HistoryLink, the Washington state online history encyclopedia. Justin is an associate director of the Library at the University of Washington, Tacoma—the campus which now surrounds the Temple and its auxiliary plots of land. Though his Library office faces the Temple, and he passes it daily, Justin also told me that once he stepped inside the Temple and walked through that hallway, he began to understand its importance.

The Temple is the only building remaining from Tacoma’s historic Japantown which still serves Tacoma’s historically Japanese American community. As public historians, I think Justin and I both felt the responsibility of telling the story for our larger community to the best of our abilities. Neither of us are Temple members, though Justin is a practicing Zen Buddhist.

Searching for the history of the Tacoma Buddhist Temple was a fascinating journey through multiple locations and archives. Justin’s experience as a university librarian was invaluable. His interests in Buddhism in America, especially Shin Buddhism (which the Tacoma Temple practices, and is part of my family history) gave us valuable context for our work, particularly the spiritual context and history. He also brought new order and organization to my research systems, creating shared digital workspaces and a virtual research library list of sources through Zotero. We looked at Densho’s online archive of interviews and images, finding valuable images of the Temple’s dedication ceremonies in particular. The Tacoma Public Library’s archives in the Northwest Room were valuable for images, as well as the “clipping file”—a manila file folder of newspaper clippings and articles related to the Temple itself, kept by Library staff over the decades. We found the Temple’s historic landmark application for the City there, although it is also available online. Most of the local newspaper coverage of the Temple has been related to its annual public events—a fall fundraiser, a sukiyaki dinner, a spring bazaar, and Bon Odori—less about the history of the Temple itself.

Justin and I also spent a couple of hours with the Temple archives—they are still in process, and mostly in boxes. We found a manuscript history of the Japanese in Tacoma. We found a scrapbook of the Reverend Sunya Pratt, a white Englishwoman who joined the Temple community in the 1930s and remained devoted to it until her death at age 88 in 1986.

We also tried to listen to the voices from within the Temple community as well. We listened to community oral history interviews with one of the previous Temple ministers, Reverend Kosho Yukawa (whose father was also a Tacoma Temple minister before World War II) and the Temple organist for decades, Mrs. Yaeko Nakano. Justin visited the Temple for a Sunday service, observing what the spiritual practices looked like. And both of us spent a morning interviewing Reverend Yukawa, the current Reverend Takashi Miyaji, and the outgoing board president, Wendy Hamai.

But some of the most surprising and valuable information came from the histories published by and within the Temple community itself. There is a book of all the Buddhist Churches of America (BCA), containing a capsule history. At major anniversaries, such as the 50th anniversary, the Temple has published booklets, including a history. We were able to see these booklets, as well as a copy of the centennial booklet in progress. The 2015 centennial history, scanned by Temple volunteer June Akita for us, was incredibly detailed and valuable, providing a wider portrait of Temple activities than we’d anticipated.

By reading the history that the Temple had kept for itself, compiled over decades through Temple newsletters and documents, we gained a fuller picture of how the community cared for each other. Because the Temple is a largely volunteer-run organization, with only one paid staff member, the responsibility for maintenance of the Temple building, not to mention the social and community life of its members, have been up to the community self. Every expansion of the kitchen, every new set of stained glass windows, every major equipment purchase (such as a movie projector for the now-defunct movie club, or the Japanese keyboard for the minister to write newsletters)—all of these have been funded by the community. Given that the Temple itself was built based on a major fundraising drive among its membership just before the Great Depression, this might not be too surprising, but to see the long record of what the sangha has done, including the nearly seven decades since returning from World War II—all of it is inspiring. Eventually, we were able to present our research in progress to the wider Tacoma community, including members of the Temple.

Even after a year of research and writing, I am still a student of the Temple’s long history. So much of what I know about Japanese American history focuses on one significant event: wartime mass incarceration. The trauma and repercussions of that event resonate to this day for so many—not only the survivors, but their descendants and their communities. The loss of Tacoma’s physical Japantown is one such echo. All the research that I’d done on Tacoma’s historic Japantown—that was prewar history, and history that many locals still know very little about.

And yet it wasn’t until I walked down that Temple hallway, knowing the story of Tacoma’s historic (and mostly extinct) Japantown, that I knew what I had missed. By focusing on Tacoma’s Japantown and its loss, I hadn’t been looking at the history of Japanese Americans in Tacoma after the war, a history which has continued for over sixty years. By focusing on the trauma that is incarceration, I had missed the opportunity to see the community’s resilience. Just because the physical buildings are mostly gone—we have two surviving—doesn’t mean that the history has disappeared, or even ended, with the incarceration. Writing about the history of the Tacoma Buddhist Temple has asked me to widen and broaden my knowledge of Japanese American history, and I am so grateful it has taken me on this journey.

© 2018 Tamiko Nimura