The relationship between Peru and Japan, historical, cultural and fraternal, is full of exemplary cases in which the exchange and modification of traditional practices occur that end up being practiced, adopted and reinvented on the other side of the world. This is the case of haiku and Peruvian writers, scholars and artists who have been captivated by this poetic genre inspired by the ephemeral and the contemplation of nature.

Perhaps the most famous haiku cultivators in Peru have been Javier Sologuren, poet member of the Generation of 50, and Alfonso Cisneros Cox. In the case of Sologuren, he was a scholar of Japanese literature (author of “ The rumor of the origin, a general anthology of Japanese literature ”, PUCP, 1993), while Cisneros Cox has been an assiduous practitioner of the same, since his first collection of poems, from 1978, until the last one from 2010 1 .

The haiku has also attracted the attention of poets such as Alberto Guillén, Arturo Corcuera, Blanca Varela and Ricardo Silva-Santisteban from Arequipa, and today it continues to be a path followed by other intellectuals interested in this poetic form of three verses without rhyme, 5, 7 and 5 syllables, which outline an eastern philosophy, with an influence from Zen Buddhism. The Japanese poet Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) defined it like this:

“Haiku is, simply, what is happening in this place, at this moment.”

And he wrote the following haiku:

The Nightingale

dreams that it becomes

in graceful willow.

Following Basho

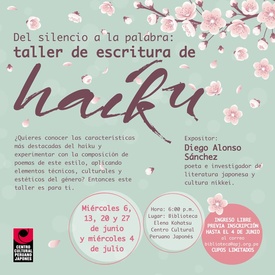

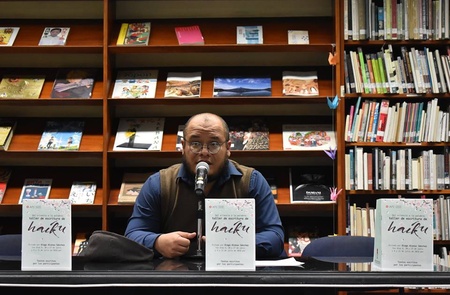

“Japanese haiku has always fascinated the West for its concise nature and explosive beauty,” says the Peruvian poet Diego Alonso Sánchez (Lima, 1981), who has been inspired by them to write some poems. “I don't consider myself writing haiku. Yes, I have had very close composition exercises, and I have adopted some criteria of its poetic genesis, but I have not achieved the mastery of the hai-jin (haiku writer).”

The reverence with which Diego treats haiku is due to the fact that he knows a lot about it. “I was born in a house full of books. My father is a poet and when I left school I expressed my desire to study literature. He recommended my first books of poetry to me and I remember with special emotion the first time he read me the poem “Franscesca”, by Ezra Pound. There I had a breaking point: I knew that I wanted to dedicate myself to writing seriously.”

At 17, Diego was already writing poetry, but haiku seemed enigmatic to him, until he read José Watanabe and then Sendas de oku , by Matsuo Basho, in a translation by Octavio Paz and Eikichi Hayashiya. “By then I already had a real desire to read poetry from Japan, but, the truth is, I had not the slightest preparation to take on the challenge.” He returned to an anthology of classic haiku published by Plaza & Janés, and then he could feel the power of nature within these short poems.

“That was, at the age of 19, my first real encounter with the poetry and aesthetics of Japan.” Later, Diego Alonso Sánchez has written collections of poems that show a clear tribute to Basho and Japanese poetry, such as “By the small inner path of Matsuo Basho” (2009), “A path begins without knowing it 2 ” (2014) and “Steps silent among fuji flowers” (2016); in addition to giving workshops to share his interest in haiku at the Peruvian Japanese Association and the Literature Student Center of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

There, among others, he shared haikus by Yosa Buson (1716-1784) like this:

A crouching warrior

on the collar of his armor...

a butterfly stops!

Haiku and academia

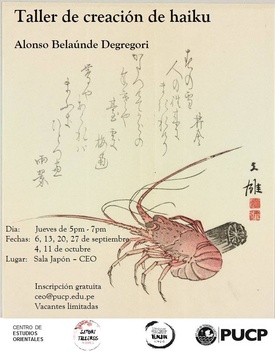

It is difficult to bring the spirit of haiku to a class, it seems like a literary species that grows best in the wild, in those intimate readings that are self-discovery and pleasure. Alonso Belaunde Degregori (Lima, 1991) has dared to do so and this year he held a haiku creation workshop, in just six sessions, at the Center for Oriental Studies of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (PUCP).

Using a collective and experimental method, Belaunde, who graduated from this same university with a thesis on haiku in the poetry of Sologuren and Cisneros Cox, believes that by learning this technique we can learn other things about life and relationships that we can have with nature. “That is what seems most valuable to me,” explains Alonso, who shares his fascination with other haiku cultivators, an intruder in Peruvian and Latin American poetics 3 .

Among the latter is the Tenjin Japanese Studies Circle and the Satori Workshops group, for research and dissemination of Japanese culture in Peru, made up of intellectuals, artists, self-taught people, academics, specialists and students, who meet to share their experiences. and learning. Alonso highlights initiatives such as that of Carlos Zúñiga Segura and Santiago Risso, creators of “Bambú”, a Peruvian haiku sheet.

Belaunde inherits a tradition that José Watanabe (Laredo, 1946) passed through, with light and profound steps, who in 2005 gave a workshop on haiku in Madrid, after having written verses like this one inspired by Basho:

At the top of the cliff

the goat and his goat frolic.

Below, the abyss.

Read, understand, translate

Rubén Silva (Lima, 1975) is a Peruvian writer, translator and linguist who was interested in poetry from a very young age. “I think it started with an interest in language: my parents are Quechua-speaking migrants, so it caught my attention to face another language that was spoken in secret. The songs were my first contacts with poetry, then at school the poetry that came in anthologies and school texts. Later it would be Vallejo and Japanese poetry already at the university.”

“I was lucky enough to meet Professor Ricardo Silva Santisteban who, although he did not read Japanese, was a great connoisseur of Japanese literature and poetry. The suggestion of this poem caught my attention, in what it does not say is its greatest meaning; simplicity, a painstaking simplicity, the aversion to easy or obvious luxury, which is also typical of Japanese food; and, finally, the love for the ephemeral, the passing of the seasons, the beauty of cherry blossoms.”

Although he has dedicated himself more to editing and writing children's books 4 , Rubén has written the collection of poems El mar es un olvido (Paracaídas, 2014), and has translated many individual poems, as well as an anthology by the poet Akiko Yosano, author of tankas. “Translating from Japanese due to the particularities of the language and writing requires great audacity and work that sometimes results in two translations of the same poem being very different from each other.”

One of his favorite haikus is by Masaoka Shiki (1867 – 1902):

Biting cold,

a village dog barks,

after a crazy

Haiku and other forms

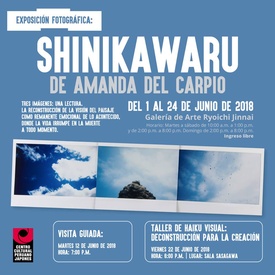

Amanda del Carpio (Lima, 1966) is a photographer whose artistic interests brought her closer to poetry and this lyrical genre. “I learned about haiku in 2010, when I started studying Japanese, so in the process of creating projects I not only get inspired or use a single line of art but several of them,” says Amanda, who was attracted by the freshness by Issa Kobayashi, simple and spontaneous, “like children and their consciousness”, among other authors such as the painter Yosa Buson.

“The one who has had the greatest impact on me is Matsuo Basho, his poems inspired me to create “ Shinikawaru ”, because his haikus not only create an image but a story in your mind when you read them.” Basho was the starting point, translating his haikus from a written language to a purely visual one, photography. His exhibition was made up of collages, like visual haikus, with images of nature that, together, seek to convey the Eastern vision of life and death.

His intention was to show Western audiences the Eastern point of view in which death is not the end of life but an opportunity for a new one. “And the haiku, especially those of Basho, have nature, the seasons, life itself to compose them as key aspects.” Subsequently, he held a workshop to share this method experimentally and freely. “Some decided to make haikus from the collages they created. Some were literal, others were more figurative, others wrote about their memories.”

From Issa Kobayashi (1763-1827) a haiku cannot be omitted:

The world in a drop of dew,

in a world of dew

and yet.

haiku moment

The haiku seems to awaken concerns, reflections and dissenting views. Diego Alonso Sánchez warns against those authors who disguise enigmatic-looking aphorisms, metaphors and rhetorical games with haiku. “I believe that there is still no true tradition of haiku in our language. Perhaps the strongest will to do so is that of the Spanish translator Vicente Haya Segovia,” he maintains.

Although there is no formula, it seems to be more of a worldview than an artistic practice. “Writing a haiku is observing and capturing a moment that illuminates us,” adds Rubén Silva, who comments that in Europe and the United States, people write haikus and there are workshops to encourage it among children. “Its relationship with Zen philosophy makes some think that it is not only poetry, but a spiritual path, at least it has helped me stop and look.”

The minimum, the everyday and commiseration are part of the thematic universe of haiku which, for Alonso Belaunde, is also lucidity and humility; allowing us to “live a more harmonious life with society, since many of the problems arise from selfishness, from believing that one's own existence is worth more than that of the rest” 5 . For Amanda del Carpio, the way of writing haiku continues to evolve, “separating itself from the way Basho revolutionized it. As long as it maintains its essence of saying a lot with few words, I think it will be fine.”

Grades:

1. The book was called “Instants” and has a digital version here .

2. With this book he won the 2013 Peruvian-Japanese Association National Poetry Contest, José Watanabe Varas Prize.

3. Sara M. Saz, “ Haiku in Latin American poetry ” (Cervantes Virtual Center)

4. “ Rubén Silva: letters without innocence ” (Andina: Agencia Peruana de Noticias, September 21, 2017)

5. Solange Avila, “ Haiku: the expression of a way of life ” (PUCP, June 2, 2017)

© 2018 Javier García Wong-Kit