Since the early days of the camera, photography has enjoyed a particular vogue in Japan. Long before the stereotyped tourist groups snapping pictures arrived on the international scene, Japanese photographers had demonstrated their talent. Japanese brands such as Olympus, Nikon, Canon, Minolta, Pentax, and Fujifilm, all firms originally founded during the interwar years, came to dominate the international film and camera market by the end of the 20th century.

While it is not clear how direct an influence Japanese shutterbugs exercised on overseas Nikkei communities, photography remained a prominent interest of those in the United States. Numerous Japanese Americans operated photo studios. Toyo Miyatake of Los Angeles was undoubtedly the most renowned, but there was also Frank S. Matsura, whose career has been highlighted in ShiPu Wang’s recent book The Other American Moderns. Matsura operated a photo studio in Okanagon, Washington in the first years of the 20th century and managed to produce thousands of images of frontier life (including striking portraits of Native Americans) before his early death from tuberculosis. Another outstanding story is that of Manabu and Saki Kohara, who settled in Alexandria, Louisiana in the 1920s and opened a photo studio that remained in the family for decades (Sydnie Kohara’s Discover Nikkei article tells the story of her family). Various Issei and Nisei worked in art photography or practiced photojournalism. One remarkable individual, Yoichi R. Okamoto, distinguished himself in both areas.

Yoichi Robert Okamoto was born in 1915, in Yonkers, New York. His father was Chobun Yonezo Okamoto, a wealthy Japanese exporter, book publisher, and real estate magnate who emigrated from Japan to the United States in 1904 and settled with his wife Shina in the New York area. He was an art patron, publisher of Japanese textbooks and author of a dozen volumes, including Bara no Kaori (the Fragrance of Roses), a set of capsule biographies of leading Americans, and Nyuyokushi naigai no jisho, a guidebook for Japanese travelers to New York. According to various newspaper stories, Yonezo’s book expounding Buddhist philosophy became a best-seller in Japan.

The young Yoichi spent three years in Japan during his early childhood, then returned for a visit in mid-1923, only to be caught up in the giant 1923 Kanto earthquake while out walking with servants. After being evacuated on an American warship and returning to the United States, the 8-year old toured with a Red Cross unit and recounted his observations of the calamity. Yoichi (known to his friends as “Oke”) grew up in Yonkers, becoming known locally as a skilled amateur magician. At some point in the 1930s, Yonezo and Shina moved back to Japan and divorced. Yonezo remarried and moved to Sierra Madre, California. Shina returned to New York and worked as a domestic servant. Yoichi settled in Scarsdale, attended Roosevelt High School, then enrolled at Colgate University. While at Colgate, he was selected as head Varsity Cheer-Leader for the school and editor of the student magazine Salmagundi. (Known on campus as a fancy dresser, he also wrote a men’s fashion column for the student newspaper The Banter).

During his Colgate years, Okamoto began concentrating on photography. He may have been influenced by his father, who owned a photography business in Japan. After graduation, he moved to Syracuse, where he worked as a candid camera photographer in local nightclubs, and studied photographic technique on the side. In 1939, Okamoto was hired as staff photographer by the Syracuse Post-Standard newspaper, and he remained in that position for three years.

In January 1942, shortly after Pearl Harbor, he entered the U.S. Army, becoming the first New York-area Nisei enlistee (he later stated that he was initially refused because of his Japanese ancestry, and it took interventions from the Mayor of Syracuse and from a friendly Army major to secure his entry). and was sent for training at the Quartermaster School at Camp Lee, Virginia. During World War II he served in the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps. In 1944, he travelled to Europe as a war correspondent. The following year, he was sent to Vienna, Austria, where he was commissioned as personal photographer to General Mark Clark, the High Commissioner in Austria. During this period, Okamoto was responsible for all photographs that were published in the American occupation zone. After being discharged with the rank of major in 1946, he joined the U.S. Information Service in Vienna, and headed the Pictorial Section. During his time in Vienna, he became a well-known figure in local social and political circles through his photos, which documented the rebuilding of the Austrian capital after the ravages of war. Among his most notable images centered on the city’s postwar cultural life, including portraits of artists and performers which were featured in a public poster campaign entitled “Schöpferisches Österreich” (Creative Austria). In 1954 the Art Club of Austria organized a show of Okamoto’s photos at Vienna’s well-known Galerie Würthle; The same year, he was honored with a silver medal by the Austrian Photographic Society for his “Contributions to the Advancement of Photography” in Austria. During these years, he married a local woman, Paula Wachter, with whom he raised two children, and learned to speak fluent German.

In 1954 he was recalled to the US, and appointed head of the Visual Materials section of the US Information Agency. He was joined by his wife Paula, who worked as a broadcaster for the Voice of America. Okamoto’s photographic work became more widely known in the United States during these years. First, he won several prizes in a 1953 contest sponsored by Photography magazine, including a snapshot of a boxer dog investigating a tiny cricket. Soon after, the renowned photographer Edward Steichen included Okamoto’s portait of Austrian dancer Harald Kreuzberger in his landmark 1955 photo exhibition “The Family of Man.” Okamoto was honored with a one-man show at the Arts Club in Washington in 1958. During these years, he remained professionally active. In 1956, he attended a four-week seminar at Indiana University on interpreting photographs. Two years later, he was invited to present the keynote address, which he entitled “How to Become a Hack,” at the annual meeting of the National Press Photographers Association. In 1961, he was retained as an instructor for the University of Missouri’s one-week summer photojournalism seminar.

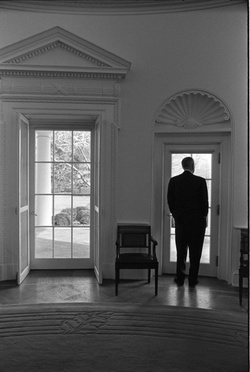

Okamoto’s career underwent a drastic shift in 1961 when he was invited by USIA director Edward R. Murrow to accompany then-Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson as his personal photographer on an official tour of Berlin, in the aftermath of the Berlin Wall’s construction. The vice President admired the photos from the trip and asked that Okamoto be assigned to him on future trips. Upon reaching the presidency, Johnson invited Okamoto to serve as official White House photographer. Okamoto accepted on the condition that he be granted unlimited access to the President, in order to capture candid portraits. During the Johnson years, Okamoto spent up to 16 hours per day at the White House, and managed to capture the highlights of history in the making: meetings with civil rights leaders, conferences on Vietnam, speeches, and so forth. Okamoto received a top secret security clearance, and would remain the only individual (other than the President’s appointment secretary Marvin Watson) permitted to walk in on the president without an appointment. In the end, he took an estimated 675,000 photos. Thanks to Okamoto’s efforts, the Johnson administration is perhaps the best-documented of presidencies in visual terms. Interestingly, Okamoto was never personally close to Johnson, whose portrait he established for posterity.

After leaving the White House, Okamoto opened a photofinishing business, Image Inc., in Washington, and pursued a career as a freelance photographer, working with his wife Paula Okamoto. In 1972 he took photographs of the aging FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover for the magazine The Nation’s Business, drawing a public expression of appreciation from Hoover for the likenesses. In 1977 he produced photographs for a special edition of Smithsonian magazine on the Supreme Court. Four years later, along with writer Bill Brock, he produced “A New Beginning,” a photodocumentary of the 1980 Republican National Convention. Sadly, Okamoto ended his own life in 1985, when he was 69. Two years later, his book Okamoto’s Vienna: The City Since the Fifties appeared. Published with the assistance of his widow Paula Okamoto, it showcased Yoichi’s photos of postwar Austria.

Even within the outstanding and underdeveloped history (no pun intended!) of Japanese American photography, the work of Yoichi “Oke” Okamoto merits further attention and study. He set the standard for White House photographers by demanding unfettered access to the president and documenting the daily events of the Johnson administration. His powerful portraits show the president in a variety of moods, and reveal the burden of the office on the man, especially during the Vietnam War. They go beyond political propaganda and shine as both art and history.

© 2018 Greg Robinson