"The guard tower had a heavy duty machine gun. Of course no one was standing directly behind it but it looked in. Later as an adult I learned another reason they locked us up was for our protection. If somebody's going to hurt us, shouldn't it be pointing out?"

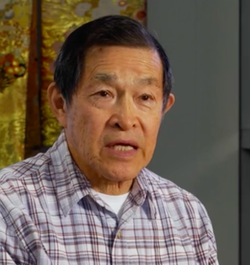

- James Tanaka

As a longtime docent at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, James Tanaka is a wealth of knowledge. He knows government documents, dates and WWII particulars by heart, and he carries a binder full of sheet protectors filled with his family’s documents and obscure paperwork from WWII that would fascinate any visitor to the museum. His family’s travels from Minidoka to a farm labor camp in Twin Falls, Idaho is featured in Uprooted, a photo and oral history exhibit about the Japanese American laborers who grew a vital war staple: sugar beets.

A crop that could be turned into munitions and synthetic rubber, sugar beet production rose exponentially after war with Japan escalated in the Philippines. As the Japanese army overtook Southeast Asia, they also took 90% of the sugar supply. Quota limits in the U.S. were lifted for sugar beet production and suddenly, cheap Japanese American labor was desperately needed in areas where they were already being held.

James’ story is from the perspective of a child – he was only eight when his family was sent to Minidoka. But his depth of familiarity now with the larger history is driven by a mix of pure curiosity and perhaps a need to know why – and how – the U.S. government pulled this off. “I’m not a historian. I’m not a professional digger, I’m an amateur digger, and these government documents are there.”

His tenacity is proof that passion and persistence will take you far in what you want to find.

What was your childhood like before the war?

I grew up in Eastern Portland, Oregon. I was under exclusion order No. 26. 24 and 25 were Western Oregon. I attended Elliot Elementary school until the third grade. We roller skated on clamp on skates. We built a club house using the wooden crates from the glass company. I went to the library and checked out books to read. We went down to the Willamette River and threw rocks into it. So most of the Japanese Americans lived on the west side of the Willamette so the neighborhood I grew up in didn’t have a lot of Japanese people in it except my family and my great uncle and aunt and their three sons. They ran the small mom and pop grocery store there and they competed with the Safeway one block away and they were able to make a go of it because they did two things that Safeway did not do. They extended credit to most of their patrons which were African American because we were mixed and a lot of African Americans were living in that section of Portland. And they also prepared the food that they ate, so one of the sons would go down to the produce market in the morning and pick up fresh mustard greens, turnip greens, collard greens and they would trim it and put it all out so people could just buy it, and wash it and cook it. And eventually the main meat that went with it was salt pork. And on Sunday morning they would sell lots of chicken. So they would buy chickens by the crate and the other son would quarter the chickens and that was their fancy meal for the week.

So they really had a good business set up.

Yeah. And then after the war I ended up being there for a year while my dad came down to LA to get trained in machine work. He didn’t have any real formal training with all the different machines.

How did your family end up in that area of Portland?

Because of the great uncle and aunt living in that side of the area. Their house was about two houses down from the store. All four of my grandparents died before I was born and they were in Hawaii, and so my parents left around the early ’30s and went to Portland. I ended up being born there so I didn’t grow up with Japanese kids, or Japanese grandparents and I’m Sansei. There weren’t a lot of us in that time frame. A lot of the Niseis were born in the ’20s. And a lot of the Sanseis were born in the ’40s. Culturally growing up in eastern Portland, I was an all-American kid.

Did you have any siblings?

Only after I was very old. My mom passed away in ’48 and then later my dad remarried so that lady could stay in America as a Japanese national – he married her just so she could get her green card. And later, when my son was born in the ’60s, my dad remarried and so that lady could stay here in America as a Japanese national, he married her just so she could get her green card. So my half sister is as old as my eldest son.

That’s an interesting family dynamic.

My grandfather left a small island that was in the Southeastern inland sea in the early 1900s and he went to Hawaii. That’s because they had that two year drought in Japan so they couldn’t pay their taxes or landlords. So they lost their tiny farm.

In digging I found out the average farm in Japan was 2.1 acres. In Hiroshima prefecture it was 1.9 acres. I was perusing Discover Nikkei and I found out that in Japan once you paid your rent and your taxes, any profit above that was all yours. So that’s when they took marginal land around them, expanded their farms, produced more money and that was in their pocket. So when they came to the U.S. they had the opportunity to lease land, which was always the poor farm land but because they knew how to make it fertile and productive in Japan, they just transferred the techniques here, and they ended up making lots of money.

I found another article from 1917, that said the average California farm had $42 of profit per acre and so if you had 100 or 200 acres in one harvest, the Japanese controlled 90% of the asparagus and strawberries, and those crops had multiple harvests during the growing season. I remember last year I was still getting strawberries from Watsonville and Salinas, so the growing season is extra long. So they didn’t make the same amount–and their farms were under 125 acres–they made not double, but $141 an acre.

And other farmers were envious, saying they got the best land which they did not get. And the government was concerned when the Japanese were being excluded and evacuated, they ended up saying, ‘Can you take over their farm and produce the same amount of food?’ And the other farmers’ corporations who took them over said, “No problem.” But they couldn’t because they didn’t have the farming technique, and the wife wasn’t working in the field. [laughs] I read a statement once working where a farmer said, “I can’t compete with the Japanese farmer! He’s got his wife working in the field with him. So those women were really hard workers because they did everything in the house and worked in the field, also.

So you came from this farming family but they also owned a store.

My grandfather when he was in Japan was not only raising satsuma tangerine oranges but he also was a blacksmith so that sort of led down to the kids learning the blacksmith trade. So they learned how to work with metal. My great Uncle and Aunt and sons started their grocery store and after my dad and mom moved from Hawaii to Portland. They tried their hand in running a grocery store, but failed.

If you’re about 83, you were–

I was seven when they opened the Portland Assembly Center, which was the exposition stockyard. They opened that May 3rd, I went in May 5th until September 4th. And then took a two day train ride to South Central Idaho, Minidoka Relocation Center. But I don’t remember having to pull the shades down.

You were one of the few Japanese families in your town. Was there any sense of discrimination especially when Pearl Harbor happened?

No I had friends, and I had African American friends. Going to public school, I remember the name, Elliot Elementary. I don’t remember having any problems.

So people in your community were pretty sympathetic to your family when you had to leave.

That part I have no recollection. I don’t even remember getting on a bus and going to the assembly center, I have little tidbits after I got there in terms of our room conditions, which was like an office type cube. The walls only provided privacy, since they did not reach the ceiling, and a cloth door. The rest room, and the fact that there was a fence with barbed wire and a guard tower. And the guard tower had a heavy duty machine gun. It was pointing down, of course no one was standing directly behind it but it looked in. Later as an adult I learned another reason they locked us up was for our protection. If somebody’s going to hurt us, shouldn’t it be pointing out?

When you were at Minidoka, what do you remember about that center and your impression of it as a young kid?

It was very different than being in wet Portland, and here it was hot and sunny. And initially, when I first started volunteering at the museum I said to people that when I first got there, this man had a dried rattlesnake skin. So two of my friends and I went walking out into the desert to look for rattlesnakes, of course we never found any. But we walked out, there’s no fence. Later I’m doing research and I learned that the museum had microfilms of the newspapers of the centers. And going through the October issue of the Minidoka Irrigator, I found that the army required that a fence be put in. And in November, they said they were putting in fire watchtowers. Of course all the other centers had guard towers, so that was one of the euphemisms they used at our center.

I remember having to wait in line to eat the American style cooking from the large cans of food. During 1942 people cleared the sagebrush and other plants and dug a large irrigation canal to water the fields to be planted in 1943 outside the residential area. And then we ate more Japanese style cooking. In my digging I found that a tofu maker plied his trade as did a miso maker from the soybeans that were grown. A pig farm was set up to breed pigs so we would have a supply of meat. A chicken farm was also set up for the eggs. For the holiday season we got to eat the older chickens.

I spent about six to seven months outside of the center after my parents got approved for a seasonal leave. The application was approved Dec. 24, 1942, so we left the center in the spring of 1943 after the FBI gave us clearance; Mr. Seaver hired my parents and we lived in a slightly better barrack apartment than the center in the Twin Falls FSA Farm Labor Camp. I remember seeing other Japanese Americans from the center living next to us. There were the migratory workers from the dust bowl days and I found out the Mexican laborers were on contract with a carrot to get them to go back to Mexico after the fall harvest of potatoes, Idaho’s fame, and sugar beets, which was to withhold 10% of their wages and be sent to a bank in Mexico near their home. Again in digging, I also found that Jamaicans and Bahamians were from England under the Lent Lease program with Europe. We were called “Evacuees” and the migratory workers were called transient whites. The farm labor camp was about 17 miles southwest of Minidoka.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on December 7, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida