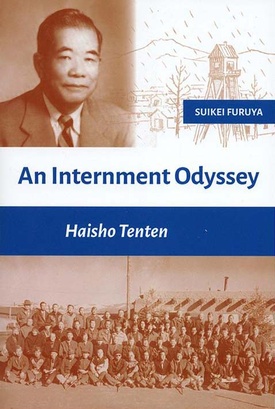

The Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i (JCCH) has been responsible — in part — for publishing three remarkable books: Life behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawaii Issei (2008); Family Torn Apart: The Internment Story of the Otokichi Muin Ozaki Family (2012); and An Internment Odyssey: Haisho Tenten (2017).

Taken together, these bountiful volumes have simultaneously achieved the following three ends: substantially enlarged the Japanese immigrant perspective on the World War II Japanese American detention experience; strategically incorporated the Hawai‘i Nikkei involvement in the heretofore mainland-dominated narrative of that experience; and considerably enriched the limited fund of information pertaining to the World War II alien enemy incarceration camps.

Like its predecessor volumes within the JCCH’s Hawai‘i incarceration story series, An Internment Odyssey provides a fascinating wartime participant-observer memoir of an Issei leader-writer, in this case via Kumaji “Suikei” Furuya (1889-1977), a prominent Honolulu businessman, community spokesperson, and progressive haiku poet. Like the protagonists of the two other series volumes, Yasutaro Soga (1873-1957) and Otokichi Muin Ozaki (1904-1983), Furuya was among the targeted group of 391 persons of Japanese ancestry arrested by the FBI on Dec. 7 and 8, 1941, in the wake of Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack. Having been previously identified as “dangerous persons,” these men were first detained and incarcerated in Hawai‘i facilities and thereafter in a series of mainland prisoner-of-war compounds. In common with Soga, who published his memoir in Japanese (in 1948 as Tessaku seikatsu) before it was translated into its 2008 English-language version, Furuya initially released his autobiographical work in Japanese (as Haisho Tenten in 1963) prior to the 2017 English translation by Tatsumi Hayashi presently under review.

While the scholarship associated with all three of the volumes noted above is impeccable and the organization of material both ingenious and reader-friendly, I was particularly captivated by certain features of An Internment Odyssey. It opens with a heartfelt, insightful, and lyrical foreword by Hawai‘i born and bred Gary Okihiro, who during his four-decade scholarly career as a historian on the U.S. mainland has arguably done more than anyone else to advance the cause and repute of Asian American and Japanese American studies. Next comes the introduction by Brian Niiya and Sheila Chun. Like everything else that Niiya has been associated with over his long and productive career in Hawai‘i and on the mainland, it is an encyclopedic tour de force. In addition to providing a cogent and authoritative overview of the Japanese American World War II social disaster, this essay richly details the life history of Furuya: as an immigrant leader and poet; his wartime incarceration experience; his family’s life in Hawai‘i during the war under martial law; his postwar return to Hawai‘i; and his later memory and representation of his wartime detention.

The piece de resistance of An Internment Odyssey, naturally enough, is Furuya’s memoir. It is primarily organized in chapters devoted to the eight incarceration camp sites in which he was detained between Dec. 7, 1941 and Nov. 13, 1945: Immigration and Naturalization Service Station (Honolulu); Sand Island Internment Camp (Honolulu); Angel Island (San Francisco); Camp McCoy (Sparta, Wis.); Camp Livingston (Livingston, La.); Fort Missoula (Missoula, Mont.); and Santa Fe Internment Camp (Santa Fe, N.M.). Each stop on Furuya’s zigzagging wartime odyssey through seven states and across some 11,000 miles is punctuated by his keen observations about the setting, the organization of the facility, the relationships between inmates and inmates and camp authorities, and the day-to-day activities of the inmates. These observations are rendered not only in concise and candid prose, but also in illuminating bursts of haiku poetry. As aptly noted by Niiya and Chun in their co-authored introduction, Furuya’s translated accounts are “virtually the only English-language descriptions of some of these camp (namely, McCoy, Forrest, and Livingston) from the perspective of an inmate (pp. xxxv).”

Over and beyond the above items, this book includes many value-added bonuses, such as information about the translator and the translation, a map delineating Furuya’s wartime odyssey, a chart indicating the days he spent at each concentration camp, a photo section that abounds with fresh images of the incarceration experience, lists of those incarcerated at several of the camp sites, four varied supplemental appendixes, and endnotes that are both precise and in-depth. Readers of this volume are also in for a rare treat: inmate-drawn maps of the Sand Island and Santa Fe concentration camps that are published for the very first time.

Let me close this review by reiterating to prospective readers of An Internment Odyssey the advice I gave to Allyson Nakamoto, a new JCCH staffer: Read this book, as well as its two companion JCCH volumes, Life Behind Barbed Wire and Family Torn Apart, as soon as possible.

AN INTERNMENT ODYSSEY: HAISHO TENTEN

By Suikei Furuya

(Honolulu: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i, 2017, 416 pp., $26, paperback)

*This article was originally published in the Nichi Bei Weekly on January 1, 2018.

© 2018 Arthur A. Hansen and Nichi Bei Weekly