Exile to Japan

Basil was nine years old when his family was exiled to Japan. He was never told the reasons why his parents chose to go to Japan rather than move to eastern Canada. He does not recall them being particularly worried about the fates of relatives in Japan, which was a compelling reason for many other families to choose to go to Japan. However, his mother did tell him much later that she was the one who made the decision, and he speculates, “I guess she chose to go to Japan because she was pissed off at how the Canadian government had treated us. No matter how hard my two aunts and grandmother tried to stop her from going, unfortunately we went.” She had a strong personality and was quite outspoken, whereas his father was more soft-spoken. Basil also doesn’t know whether his parents later regretted the move to Japan as they did not talk about it with their children, although many years later his mother did indicate during a visit to Canada that she wanted to stay with Basil’s family in Vancouver rather than return to Japan.

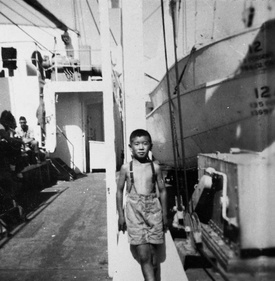

Basil’s family were taken to Japan aboard the General Meigs, the largest of three American ships chartered by the Canadian government specifically for the deportations of Japanese Canadians. He recalls being sea sick during the voyage to Japan. One day, after he began to feel better, he wandered up to the galley and met a black man working there who befriended him. Subsequently, Basil would occasionally go up and see him late at night and he would give Basil something to eat. “Whenever I missed my meal, he was there and I just had to go and see him and he would feed me. It didn’t happen very often.” Basil doesn’t remember much else about the voyage.

When the ship arrived in Yokosuka, they stayed there for several days while arrangements for transportation to his father’s home village were being made. Basil remembers seeing the wreckage of airplanes and ships which had been bombed and sunk in the harbor. It was quite hot as it was summer. The quality of the food they received was extremely poor. He recalls, “The part that scared the hell out of me was seeing wiggly bugs in the food. It was a kind of stew with rice, and on top of that they had fukujinzuke pickles—my first time to taste fukujinzuke which I still make from time to time. We were fed biscuits that were really hard like dog biscuits—it was a good thing I had strong teeth back then. We survived the food and fortunately did not get food poisoning or anything like that.”

They travelled by train to his father’s village, Shimasato, Wakayama. Basil has few memories of the trip or the conditions in the train, but does recall that when the train went through a tunnel there was a very strong unpleasant smell of coal smoke which came in through the windows. He also recalls making one stop somewhere during the journey and transferring to another train. After arriving they lived together with his father’s parents.

His mother soon left for Osaka where she was quickly able to acquire good employment with the American occupying forces1. Basil remembers his father ‘coming and going’ but does not know what kind of work he was doing. He doesn’t recall much tension generally between his family and relatives in his father’s home village, but clearly remembers the personality of his paternal grandmother who often got angry, particularly at his mother. Although Basil does not recall the specific reasons why, he thinks it may have been partly because his mother had left the family in Wakayama while she went and worked in Osaka. He says, “There was some resentment shown by my grandmother; she blew her top quite a lot. My mother was not of much help as she went to Osaka to look for a job right away, so it was just my dad, my two sisters, and me. Dad’s mother was pretty headstrong.”

Basil does not recall experiencing any shortage of food during this time, which might help explain why he has no memories of his family being resented by his relatives and other people in the village as many other exiles were. He says, “If my relatives resented us, it went over my head. I didn’t pay too much attention — I just did my usual things — went to school, went fishing, swam in the ocean, did some skin diving, made a homemade spear gun, and caught ise ebi (a kind of shrimp). I was able to feed myself with seafood. Sometimes I caught abalone. I was able to swim and catch a lot of stuff. Another time I went fishing in the river. I noticed that I’d caught something and brought it up, and at first I thought it was a snake, but the people around me told me that it was an unagi (eel), so I took it home and ate it.”

When Basil’s family moved to Japan, his Japanese speaking level was still not very high, and he couldn’t read kanji (Chinese characters). Studying Japanese had been officially forbidden in the camps although done secretly. He recalls that they did have “a sort of underground Japanese schools” in the internment camps which used really old school textbooks, but he didn't progress beyond the primary level. Due to his limited Japanese, he was moved back to grade one although he was nine years old (at that time Japanese kids started grade one at eight years of age, so he was only one year behind). He says, “I was ok at math, but soroban was a lost cause for me and I never used it again.” He doesn’t think he had a particularly difficult time communicating with teachers or classmates: “I was more English orientated, but held my own in Japanese.”

Even as a nine-year-old child-exile in Japan, Basil felt very proud of being Canadian, and his trademark was his maple leaf sweater. He says, “At school they knew I had come from North America. In those days they did not distinguish between Canada and America and called me an American. I resented being called an American rather than a Canadian, and at least once got into a fight about that. At that time I had long hair, so I had my dad cut it off and I became a bozu (shaved head) like the other kids because the other kids could pull my hair in a fight if it was longer. I got into the normal fights that normal kids get into, but I do not recall being picked on for being a foreigner. I just resented being called an American.”2

He also recalls playing baseball: “The thing I enjoyed was playing baseball. The ball that was used there was not the kind that we use here. They used a very hard rubber ball. I could hit better than the other kids, and I was slightly bigger than the other kids. My baseball skills helped me then.”

Return to Canada

When Basil was twelve, his maternal grandmother and aunts, who had stayed in Canada and were living in Vernon, a fruit-growing town in the interior of BC at the north end of Lake Okanagan, began the process of sponsoring him back to Canada. He does not remember whether he himself had a strong desire at that time to return to Canada, but he believes that his parents initiated it. He does recall his father telling him that he thought it would be a good idea for Basil to return to Canada before he forgot English and became too entrenched in Japan. However, Basil never heard anything from his father that indicated his father himself also wanted to come back to Canada. After three years of living together with his father and younger sisters in Japan, Basil returned to Canada and stayed with his aunts and grandmother in Vernon.

His mother had made arrangements for him to travel with three young men who were going to Kelowna, which is located near Vernon. That arrangement apparently worked out well as he would arrive in Vernon safely. The ship stopped over for one day at Hawaii, then landed in San Francisco. During this voyage, Basil experienced the very surprising coincidence of meeting the same black man who had worked in the galley and had befriended and fed him during the voyage to Japan on the General Meigs several years earlier. Amazingly, he still remembered Basil. Basil and his three companions stayed in San Francisco for several days until they could get a booking on the train (Southern Pacific Line) from Oakland to Portland, where they transferred to Northern Pacific Line and went on to Vancouver, and finally on to their destinations in Kelowna and Vernon.

Notes:

1. Basil is not sure exactly what kind of work it was, but due to her native English and strong education, it can be assumed that it most likely involved translation and interpreting.

2. Basil seems to downplay the discriminatory and racist nuance of being an ‘America-jin’, perhaps because of his young age at the time. Older child-exiles who were called this strongly took it as an intentional bullying insult and some were severely traumatized and avoided going to school, for example, George Kawabata (Tanaka, 21).

* This series is an abridged version of the original article titled, “A Japanese Canadian Child-Exile: The Life History of Basil Izumi,” originally published in The Journal of the Institute for Language and Culture, Konan University, Vol. 22, pp. 71-108 (March 2018).

© 2018 Stanley Kirk