Can you tell me about the picture of you and your friend looking at the fire?

My friend and I could see the fire on the opposite side of the camp. It was the auditorium where they used to show movies. We could see the flames and the smoke just billowing in that direction, and of course hear the sirens in the distance. So we were watching and we could see the design of the camp. The man was the from the same block and taking pictures and he said, “Stand just like that.” And we were wondering if we should turn around and he said, “No, no look at the fire.”

What do you remember seeing?

I was impressionable, and I was observing this. Just unhealthy. Adults with nothing to do, it must’ve been all that kind of hopelessness. The men were just doing what they felt. So the propensity of gambling among Japanese was prevalent and they had a casino-like atmosphere. And if you enjoyed drinking, well, they needed something to stimulate them, I guess. So they made this moonshine out of rice but it would make them very sick and they would throw up. You could hear them coming home in the middle of the night. My uncle, he was doing that even in Topaz. He wouldn’t come home for weeks.

Where did he go? Just wandering around?

Just gambling. Maybe he had a girlfriend, I don’t think so. Everything was out of whack. The negative part of the Japanese really surfaced in Tule Lake, I think. The U.S. government used Tule Lake as an experiment to see what the culture, their education and behavior. They knew they were going to win the war.

What was one of the worst things you remember seeing?

There were at least three homicides. One was a guard, an American sentryman shooting a truck driver. They got into an argument. The driver, who was able to go in and out of the gates, didn’t show his pass or badge which was supposed to be clipped onto his pocket. And the guy didn’t talk to him nicely, and the Japanese kid shouted back. So when he came back, the guard was still mad so he just shot him. And there were two or three homicides but they were killings done within the camp. It was a known fact, it was dangerous to walk at night around Tule Lake because you’d get beat up or jumped on.

But this was only a problem between people who were divided along the two ideologies, right?

Yeah. And you knew where they were from if you got into an argument, pro or con Japanese. There’s nowhere else to go, everyone lives in the same type of barrack, so you’re marked. There’s no security and so people were bursting in and people were beating up the guy or the husband. I heard that going around. And my dad, I think, was involved and that was the reason he was taken away from Topaz. I saw him get handcuffed and taken away as I was coming home from school. He looked at me but didn’t even acknowledge. It was just my mom and I who went to Tule Lake in Block 49 and he either went to Crystal City or Leupp.

One day he came home and was released. He got into the same mode, teaching Japanese in high school. But there was an argument in the next block, with a crowd forming of people yelling at each other. I remember my dad going out there, too. He was relatively tall back then compared to other Japanese so he stood out.

So, was he going around beating people up?

That part I can’t confirm. But I know he was considered dangerous according to an FBI report.

Where did you read that report?

He had it stashed away at their house.

Did he have friends?

Oh yeah, he had a lot of friends. They were all in that Kibei group.

So then from Tule Lake, maybe a year went by after he came home, and here again I came around the corner and he was taken away. So I watched him twice being handcuffed. And this time he was taken to Leupp, Arizona. Years later they would advertise getting this group together and write it in hiragana and katakana. It would be at a Chinese restaurant or somewhere in Japantown. They’re all sitting around, all these pompous looking people, so cocky. The way they posed, just full of themselves. They used to walk around with zoot suit pants and so they brought their own style to the camps.

Maybe at some point, it became a badge of honor for them.

They’re fighting their own war in their mind. No one in Japan cares a hoot about what they’re doing for Japan, or if they were. It’s not psychoanalyzing them but maybe it was the only way they kept their self-esteem. They returned from Japan after an education over there, and English skills were nothing. So they felt left out. Then they felt indignant or animosity towards Niseis because Niseis would be fluent in English. So maybe that was their little way of rebelling. But the war they were fighting in their mind was to resist what was happening, which was unlawful imprisonment.

I understand his point of view and see it as something honorable. But you being a child, I think your perspective was different because you just wanted your dad to be a father. Maybe you came away with more resentment?

That divisiveness just carried over after the war. There was the wall between the Niseis and the Japanese. They were incapable of talking because of the language barrier. And Japanese is a hard language to pick up so the Niseis didn’t care to learn to speak Japanese. What for? Their workplace and job was all English. You had to assimilate.

What was school like in Tule Lake? You had a pro-Japanese and Japanese-only speaking experience.

Although the government provided junior and high school, if we attended, we were called inus, dogs, which was like a traitor. So no one attended. And it was backed by the administrators that they could form their own system, the Japanese language school. So there were eight of them. The format was exactly like Japan. They were preparing us to go back, so it had to be that military style education. We had to put on a headband, hachimaki. White color for the boys, red for the girls, and meet at the undokai, meaning exercise field. So we did our taiso, and then we had to bow eastward and shout Tennoheika bonzai! Long live the emperor ten thousand years.

But I thought about this later, that California was closer if you faced Japan west, where if you face east, you’re almost three-quarters around the world. I thought, “What a bunch of idiots.” [laughs] But we were bowing east towards the sun, tennoheika bonzai! But when it became radical, sometimes we had to get on our knees and bow. Usually we would bow politely from the waist but sometimes he would make us kneel. “Seiza!” And one time after a storm, there was a mud puddle where I stood in formation. So I just moved over like an inch to avoid dirtying my pants, and the teacher came and hit me on the head because I moved. That was a prominent part. I had a lifetime of watching people slapping each other. But you started getting conditioned because we were running, washoi washoi. You’d go around running in formation. There are pictures and it looks just like Japan, preparing for war.

Can you tell the story about being in class and needing to go to the bathroom?

I raised my hand and I had to go pee. “Sensei, benjo ni ikitai.” And he says, “Gaman shiro!” He told me to hold it. I couldn’t talk back. And I couldn’t hold it. So anyway, I peed in my pants where nobody noticed, and during recess, I dashed home and changed. But there were punishments if you mispronounced in reading. I remember one time out in the snow, I had to hold my book up straight and read two pages over and over. Because I mispronounced some phrase in there, and there might have been some words or kanji which I didn’t study. So that was my punishment and he said, “Go outside and read it.” And I had to read out loud. And he’d peek out once in a while and say, “Kiko-en zo!” I can’t hear you! [laughs].

Who were these teachers that they got?

All these Kibeis. I just had this total disdain for them. They were a bunch of kooks. If they felt like it they just slapped you around. I wish I was big enough, and if I was in high school, I would’ve just broke his nose.

I know. You would’ve been sent away for sure.

I would have. Because I wouldn’t have put up with it.

Can you describe what happened when Grandpa came back to Tule Lake and he decided to go back to Japan?

Basically all the people in Tule Lake were classified disloyal and they all wanted to go back to Japan. So the preparation for us was we packed what little we had and a seamstress made me an overcoat because Japan was going to be cold. The war had not ended yet. My dad thought that Japan was not losing the war, even though there were photos of Japan being devastated. We already saw the aftermath of the atom bomb.

Where did you see that?

It was in Life magazine. But even my dad was telling me that those were not true photos. That’s pretty sad.

He thought it was propaganda?

Yeah, that it was propaganda. So the day before we were going to head out and take the train to the port, a friend of his who was part of the crew on the boat got into the camp. He visited and told my dad to not go back. “Tsuchida-san, ima nihon ni kaettara dame desu yo.” Going back to Japan right now would be bad. The devastation is surreal. He said, ‘Japan is just totally devastated with nothing to eat except jagaimo [mountain potatoes]. And you’re going to be treated badly because they’re so bitter over there. You think you’re going back to be a true, loyal Japanese but you’re wrong, they’re going to think you’re the enemy.’ And my mom started to cry.

Because she wanted to go back?

No because she didn’t want to go to the depot area and unload the crate. She just objected to that. [laughs] People that did go back anyway, and met my family again later, they all said the same thing. ‘It’s a good thing you didn’t go back.’

So she didn’t care either way, going back to Japan or staying?

She said, “Go back yourself if you want and I’ll stay and raise Mitsuki by myself.” And which she managed to do, of course. We came out of camp and we disembarked at Berkeley for no other reason except that she said she used to hear the bells chime at the UC campus, at Campanile, and she thought it was pretty. So she got off at the train station at Berkeley, nowhere to go with only $25 in her purse, looking for a place to live.

How did Grandma take care of you?

We found a Christian church with four or five other families already living there. We slept there for a good two weeks. Then we found this place at 2815 Grant Street. And we were squeezed in like sardines. In fact, it was worse than the camps. Because the U.S. government just wanted to get rid of the Japanese. It was costing them a lot of money to feed everyone. They told all the people in Tule Lake, ‘Either go back to Japan or leave.’ So there was this struggle to find a place to live, so that’s how we ended up in Berkeley. That’s where I met all of my surrogate brothers and sisters because we were all clustered in this ten block area.

When did you finally reunite with your dad?

I think it was February 1947.

Wow, really?

When we went to the train station, it was the end of the line in Oakland. My mom and my cousin’s dad drove us to the train station. I could picture him walking down, he had a distinct walk.

He refused to a sign a pardon or write a letter to the U.S. government, apologizing for his behavior. It was just a symbolic thing. And he refused to. So our demise financially was compounded. My mom only, in Berkeley. And everyone came back by 1945 and you know, gardening and working, earning what little money. And so we were poor, just depending on my mother’s income which was cleaning houses. So here again like in camp, I’m running around, no one’s watching me. And I’m running all around town.

I can’t believe he was one of the last people out. Did he ever write that letter?

Yeah, someone went to talk to him. “Look, your wife and your son are waiting. All you need to do is confess that you were wrong,” or something. The FBI filed grandpa as hot-tempered and violent, and that supervisor said, “No, Tom is not like that.”

You mean a Japanese friend?

No, the camp supervisor. [laughs]. The supervisor said they would write it for them. He could not write a lick of English.

What happened after you started living in Berkeley?

My part of being slow to pick up the language was because we didn’t speak at home. And I figured out later that all my other friends were at home with a lot of siblings, and all they did was speak English. So the Kibei or Issei parents were left out. I would be invited over for dinner, and I thought it was a big party. But they spoke among each other in English. I was an anomaly because I was the only child. All my pals picked up English quickly.

And by the time I got to junior high and high school, my interests were different. It was cliquish.

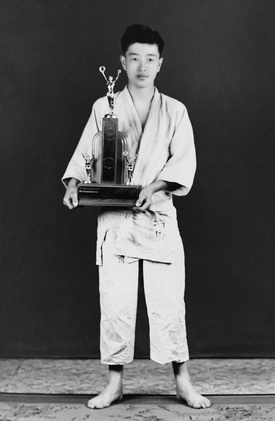

And then my influence came because of judo, and even though I was a high schooler, I was pretty good so I was beating up college guys from San Jose State, Cal Berkeley or San Francisco State. So my influence was from guys who were three or four years older, hakujins, who instilled on me the value of education. But that’s where I picked up a lot of history and information because they were knowledgable.

So that part among my high school friends, they didn’t really know me. Girls thought I was quiet. But it was my financial situation, too. We were poor. I didn’t have a car. So if I wanted to date, I didn’t have a car to drive to pick up the girl. And so when I went to senior ball, that was unusual. That was the only time I went out. It was a big deal, I rented a white dinner jacket. So here again, I wanted to ask Diane [Tsukamoto] but then I had that lack of confidence. I saw Diane’s father once, just this rigid, pure army man. Distinguished looking of course but he intimidated me. I thought if I go to pick her up, “What’s your name again?” Tsuchida. “Where do you live?” And see I’m embarrassed from there. I live down on Grove Street in a rental house with four or five other families. I managed to borrow my dad’s 1942 Roadmaster Buick, sounded like a tank going down. But she lived in a nice house, with the military benefits. So I didn’t want to meet him at the door. “You get Diane back here by midnight, you hear? And by the way, are you going to college?” or something [laughs].

How did you feel about receiving your apology and redress?

I was aware the movement was ongoing. I personally knew Edison Uno. He helped start the movement. So yes, but I didn’t care. I was apathetic. Because I was so disgusted with the way we were treated, I wanted to forget about it. It’s justified, I thought, ‘Good for them!’ Heck yeah they should be doing it. But it got where I became jaded. How wrong is that? You got an American citizen being treated like an enemy, I was just a kid.

Was Grandpa part of the redress movement?

Yes. Even though being an enemy of the country, so to speak, he was selected to testify in San Francisco at the Federal building.

Who picked him?

Don’t know. Because he was the wrong guy to pick.

Why do you think it was a bad choice? It seems like he would be the right person to pick.

Yeah, I guess you’re right. He had a confrontation with Hayakawa in the hallway. He said it was like a welcome respite for the farmworkers. Hayakawa did approach him and my dad issued a counter-challenge. Said let’s just set up a forum and we’ll have an interpreter.

To just debate?

Yes to just debate. But that didn’t happen. Hayakawa was a coward.

Did you ever read Grandpa’s testimony?

No.

Do you think you felt apathetic because you were so young?

That’s a good question. I didn’t know which way to go. Here I’m trying to learn English with Kibei parents. I was messed up. Then we went into a place where all these people in Tule Lake who were considered disloyal to the U.S. but loyal to Japan. But they were justified because they were being mistreated. Tule Lake was unlike the other nine camps. They were preparing us for when the Japanese army invaded, we had to help. We had these sticks pointed, like we were going to fight the American soldiers. They were preparing us to go back to Japan.

Why do you think the redress experience never politicized you like it did other people?

Everyone was feeling sorry for themselves, maybe. I didn’t want to fall into a trap of victimization as to what happened to us. Because my dad just couldn’t forget it. I think he became even more weird, cynical because of that. But my dad had his place in the sun. Four of the major newspapers in Japan came to interview him. They came to the house at different times. So he finally got someone to listen to him. They took his story.

I didn’t want to fall into that trap that I was victimized. I got sick of it. I don’t care.

Except now. How come you were willing to tell me so much?

It started to leak out here and there. I remember you typing rapidly, it was sputter and go, I remember. I wasn’t as fluid. But the questions started to make me remember. It’s getting more focused. It made me think, this story should not die down.

But when you hear the history of Native Americans, African Americans and what they went through. It’s somewhat cathartic, it wasn’t bad for us. The slave ships, chained. Being lynched without impunity. You know, Manzanar, there was that tribe there. And they’re all forced to walk the Trail of Tears.

It’s all just a pattern of racism. It’s symptomatic of the same problem.

It’s been happening throughout history. It’s been going on. If you think about what the Americans did to the slaves or Indians, it’s terrible what they went through. So our three, four years, it was nothing.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on Octber 14, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida