In the late 1960s, a group of Los Angeles Japanese American ex-gang members, many at the time either fresh out of correctional facilities or the military, came together to save a generation. They called themselves the Yellow Brotherhood, and organized to get at-risk Asian American youth off drugs and out of gangs. They were particularly active in the early 1970s as a direct result of thirty-some Japanese American youth deaths in one year by drug overdose in the Los Angeles area; the Japanese American establishment of the time attributed these passings to mysterious heart attacks, the elder generations unwilling to acknowledge such behavior within the community.

During the postwar resettlement period of the 1940s, hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans returning to the West Coast post-WWII—as a result of Ex parte Endo declaring that regardless of cultural descent, loyal American citizens could not be detained without cause—were released from America’s Concentration Camps but nevertheless ran into restrictive housing covenants, racial discrimination in the work place, and plain old racism from “Jap” haters. My grandmother’s brother, for instance, upon his return to California from fighting with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated Japanese American unit and the most highly decorated American military unit for its size and duration of service in U.S. history, went to get a haircut only to have the barber tell him he would not cut “Jap hair.” Never mind he was a decorated veteran of the United States Army who fought the Axis Powers in such storied European campaigns as the Rescue of the Lost Battalion and the Gothic Line. “Jap hair.” It was in this climate that they returned to begin their lives anew.

Many Nisei, the first native born Americans of Japanese immigrant parentage and the ones who largely had their burgeoning careers stripped from them during Evacuation, were too busy rebuilding their livelihoods postwar to know what their Sansei (third generation) children were up to. As the Sansei came of age in the inner cities of the 1960s, many were faced with their own sort of exclusion. It wasn’t the exclusion their parents had faced; it wasn’t a loss of livelihood and unjust incarceration in desert-stranded wood-slatted barracks, but “Beat a Jap Day” in school every December 7th wasn’t too cool either. In some neighborhoods, the youth turned to drugs while others fought back through the formation of Japanese American street gangs.

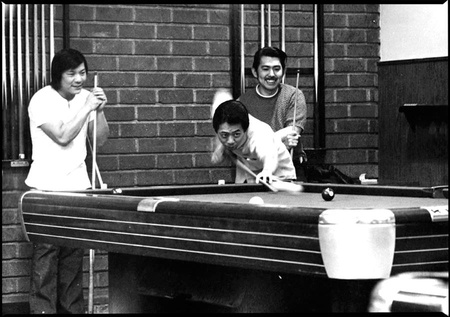

In early 1970s Los Angeles, the Yellow Brotherhood raised enough money to purchase a house on Crenshaw Boulevard, near Pico. There they tutored students, assisted them with homework, promoted physical fitness, educated the youth about their community’s history not to be found in school books, taught them to be proud of who they were, and as ex-gangsters were not above physical violence as a reform method for junkies—they literally scared some kids straight, saving a generation of underserved youngsters through peer counseling.

Growing up in Chicago, I’d never heard of such a thing. Relocatees in the Midwest were told to suck it up and assimilate. My grandparents’ families, formerly evacuated from their homes in California to Heart Mountain & Gila River War Relocation Centers in Wyoming and Arizona respectively, were advised upon release to not congregate with other Americans of Japanese ancestry. As a result, I grew up apart from this history and so when I moved to Los Angeles in 1998 for work, I dove into the Little Tokyo community to get a sense of what had been left behind.

Among the local community stalwarts, I got to know Art Ishii. Art, a Sansei who grew up in the Los Angeles neighborhoods of the Westside and J-Flats, had co-founded the Yellow Brotherhood along with Gary Asamura, Mike Goodlow, Laurence Lee, Ats Sasaki, Victor Shibata, and Dave Yanagi. In a July, 1973 article of GIDRA, a monthly newspaper published from 1969-1974 and dubbed “The Voice of the Asian American Movement,” Art expressed the following:

“The Brotherhood was composed of street people. Not just regular street people, but Asian street people. And these were some strong brothers. When you talk about togetherness, the Yellow Brotherhood had togetherness. It was obvious that we had the greatest amount of respect for each other.”

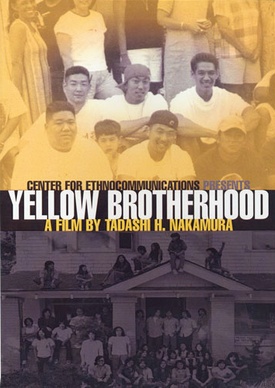

In 2003, a Los Angeles-based filmmaker named Tad Nakamura who had grown up playing on a basketball team organized by former “YB” members, directed a short documentary entitled YELLOW BROTHERHOOD. As an appreciative gesture, Art Ishii—being one of the interviewees for the film—received some promotional loot in the form of YB baseball caps and t-shirts. He gifted me one of each, and thus began the conversations.

Over a decade later, the shirt is showing some wear. It may not have much life left. Many of my Chicago friends and family have wondered what it means, and to this day I know conversations will be had on mornings I pick it from the closet. I’ve been asked what it means by strangers in such innocuous places as the grocery store checkout line. So, before it gets too many holes to wear anymore, this is the story.

© 2017 Erik Matsunaga