“The Japanese people are not the kind of people to sit back and feel bitter and feel sorry for themselves. They are creative, resourceful and they make the best of a bad situation. Shikata ga nai.”

— Alice Kanagaki

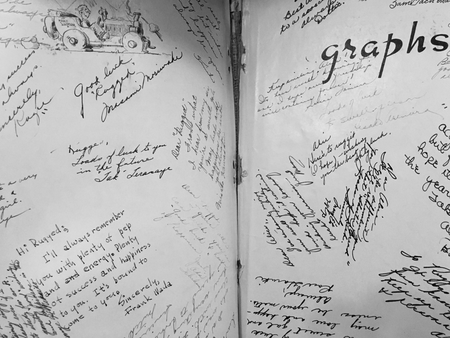

Teenage fun, good friends, and happy memories of high school is how Alice remembers her time in Gila River. Skim through her high school yearbook and it reads like an average collection of young friends in any other school bonded by dances, sports, and an impending separation of graduation. Several of her handwritten messages begin with “Dear Rugged.” I asked Alice how she got the nickname. “Probably because I was athletic and played softball and was good at it,” she says.

Shortly after the camps closed, Alice joined the Cadet Nurse Corps, a government-sponsored program that aimed to fill the staffing void left in civilian hospitals across the country. The program included a vital non-discrimination clause, and was open to young women of any race, including Blacks, American Indians and the Japanese Americans. Alice’s cousin was already going to nursing school in Madison, Wisconsin, and so she too applied. “The government paid for everything and we had wonderful uniforms and were the largest, youngest uniformed group of women serving the country. It saved the civilian hospitals from closure. From teenagers we became adults in no time,” she says.

Now at 90 years old, she refers to herself (and other Japanese Americans who have reached their 90s) an “endangered species.”

* * * * *

My hometown is in Vacaville, California and I was born, reared, and educated there. My father, like many of the other Japanese Isseis, worked on fruit ranches. And what they did is rent 500 acres of a particular fruit ranch and they would be in charge of taking care of the trees and harvesting and hiring of the workers. So when my father was in his late 60s, he felt he was too old to continue with this sort of thing and he wasn’t making a lot of money. Most of us were poor, of course we lived through the depression. And only a few people were doing well, meaning, comfortable enough to send their kids to college or buy a new car.

So my father bought a small mom and pop store in Martinez, California in 1941. And then of course Pearl Harbor happened in December. Martinez became a restricted area because it was close to the Benicia naval weapons and shipyard. So my parents moved to Concord and lived in the garage of some friends and my father said, “Well, there are rumors that we’re all going to be sent somewhere. So we might as go with our cousins who lived in Suisun.” And they weren’t happy living in the garage, of course. So they sold whatever was in the store and moved to Suisun so we could be evacuated with our cousins.

When the time came to when we were to be leaving—you’ve heard—we were only allowed to take what we could carry. And some kind people stored whatever possessions or whatever furniture we had. Then we went off to Turlock, the assembly center. Turlock had a racetrack park. Some of the families lived in horse stalls. Now, a family of six, were assigned one horse stall which was smelly and messy and they had to clean it out. And we were given army cots to sleep on and I think we had to fill our own mattresses with hay. But my family, we were assigned one of the rooms in tarpaper barracks, with black tar floors. And in the summertime it was so hot, the legs of the cots would sink into it. So we survived and young people, people in general, we had fun. They know how to make fun. We had dances, classes of different kinds, and sports.

So after the summer we were all sent to Gila River, Arizona. Our family was sent to Butte camp and there we met people from all over California. And camp life, for a fifteen year old, was fun and adventurous because suddenly there were all these teenagers of Japanese descent that I could meet and make friends. The food wasn’t that great. But we always had rice and the Japanese people are very resourceful and very creative so we had okazu [side dishes] of different kinds, often vegetables. And eventually, these clever farmers were able to get some water from the canals and they grew produce gardens. I think they grew the best melons that were ever grown. The state of Arizona initially said, “No, we don’t want those Japs in our state.” But two camps were built there: Poston and Gila River. And nevertheless we went, and within those camps and when they saw how clever the Japanese were as farmers they said, “Oh we’re glad you’re here. And when you leave camp we want you to stay and teach us how to grow produce.” [laughs]

Did your father also farm in camp?

My father was the kitchen supervisor and my mother was a waitress. Pay in camp for people who were professionals [doctors, teachers, supervisors] were paid $19 a month and workers were getting $16 a month. Now the camps are like little villages.

And the school that was built was that the curriculum was adequate for college entrance. So many of the kids who left camp went to college because they were able to take the subjects preparatory to college. It was a good school system, I would say. The teachers were Caucasians from outside and also teachers who were college-educated or teachers within the camp. So we had some pretty sharp teachers and of course lots of sports. Now, the Japanese people are not the kind of people to sit back and feel bitter and feel sorry for themselves. They are creative, resourceful and they make the best of a bad situation. Shikata ga nai [It can’t be helped]. And that’s what they did I’m sure in every camp. Like my mother, she started to take English classes, and she learned how to sew. She made a lot of friends with other Issei ladies who came from other parts of California. And she even cut off her hair–which she always wore in a bun– and got a permanent. My mother got a permanent and my father almost had a stroke.

Maybe she felt somewhat liberated?

In general, I think those who had a positive attitude learned to enjoy themselves and make the most of it. My father was tickled pink because he could play poker, he found some poke buddies to play with.

And my brothers of course played baseball and I played softball and basketball, whatever sports they gave us. And then we all learned how to dance because there were dances every weekend. For the first time there were so many boys of my age. I was the wallflower type but it was fun to be able to flirt with all these guys because a Nisei boy of our own age were kind of scant in the high schools we all went to. There was a high school annual. It was really quite elaborate. There were a lot of good artists so the artwork in these yearbooks is pretty clever. I graduated in the class of ’44. And it had the usual–the campus queen contest, sports and so on.

And the interesting thing was this camp was built on an Indian reservation and the indians in the beginning were very curious to see what these Japanese people looked like. So in the evenings we would see them come to look at us. We saw the young Indians riding horses. And they all made friends and in time, the Indian boys and high school Japanese boys had intramural sports tournaments.

Wow, that’s really interesting. Not surprising that friendships were formed across the two communities.

A high school in Phoenix had a Girls League Day. And they invited two girls to go from our high school and they chose my friend and myself to go. Why me? I don’t know, maybe because I’m a blabber mouth. My friend was a beautiful girl who was about 5’8–unusual for a Nisei girl–and very attractive and smart, and so I think they wanted her to be the good representative from our high school.

We met so many wonderful girls and had so much fun. So we invited them to come to our high school for some special event. And so a large group for these Caucasian girls came to our camp to see what it was like. We all made some friends and I remember corresponding with one of the gals. My experiences are through the eyes of a 15-year-old. And teenagers you know, we look to see where we could have fun, right?

Yes.

So when I describe camp life, I have been told by some people: Why do you make it sound like it was a vacation? Well, in a sense it was. Because I didn’t have to work out in the fields to help with the prune picking, and there was only one room to clean. I helped my mother with the laundry but other than that I didn’t have any chores. I had lots of friends and we had sports and dances and everything so in a way it did seem like a vacation to me.

Do you think your experience in Gila was different from a camp like Tule Lake, for example?

All of the camps were similar. I’m sure they did the same things we did. It was the same kind of entertainment and schooling, although I heard our high school was a little better than the others. But as far as Tule Lake goes, I have no idea what the attitude of the teenagers were there, or what their hopes and fears were. I think they were kind of out in limbo, they didn’t know what their parents were going to do: Go to Japan or leave camp? I have one friend that was there and she really doesn’t want to talk about it. I don’t think they had the happy experiences that we did. I think there was resentment and the attitude was a little different in the entire camp.

Do you believe that your parents felt the same way? Did you talk to your parents about what was happening?

In the beginning, they were devastated because of a lack of an income and the feeling of uncertainty: What are they really going to do with us? Will we be sent to Japan? Will we be all killed? The interesting thing is my older brother was already in the service long before Pearl Harbor, he was drafted. My mother initially did lose some weight then she got accustomed to making the most of life and so she did thrive, you might say, while in camp those short few years. When the camps closed my parents went to Chicago and they got jobs and they worked hard and saved their money until retirement and were able to come back to Berkeley and purchase a house.

Now camp life, people may not agree with me but there was no point in being bitter about it. It happened, it was wartime, and the JACL did what they could but they were weak. Maybe the members were in their twenties and they had no power so even though they objected to the fact we had to go into camps as citizens as the U.S., there was no one who could stand up for us. They were somehow a threat and when the idea to put us in camp arose everyone said, “How is it that they already had plans, more or less?” When that bill was passed, it was just a few months, those camps went up. And it takes a lot of planning locating where and what state they can build it, and somehow all of this was preliminary. Isn’t it peculiar that they already had plans for us even before Pearl Harbor?

So when you received the redress, can you describe what your feelings were about it?

Not really because initially, I think the government tried to make up some of the losses. They tried to give the internees a small sum of money to make up and I think my family got a couple of thousand because we had that little mom and pop store. When all this talk about redress was going around, I went to those committee meeting. He came and told us, “You deserve that money. Don’t feel so loyal and patriotic that you don’t deserve it.” The government did something that did very wrong so you deserve that $20,000. there were a couple of people that rejected it. Our situation was very helpful, it put a new roof on our house. So the attitudes were different for different people and I think they changed after they heard this Nisei judge from Pennsylvania tell us that. Be proud to accept that money.

I’m sure it was really a drop in the bucket in comparison to what your parents could have made with their businesses. It’s hardly enough.

That’s true, it’s hardly enough. A lot of people lost their homes, and their homes were trashed and their valuable property was stolen. We didn’t have anything of importance–just pictures, family pictures. This nice family had stored it for us but people broke in and trashed it all so we didn’t get any of that back. All those school pictures you enjoy looking at as an adult? Those things were all trashed.

It was being held by a white family?

In our particular case, the little mom and pop store, the people that owned it were a prominent family named Amato in Martinez, they owned that property. And so when we had to leave, there was a large walk-in closet and they said you can store your valuables there and we’ll make sure it’s blocked and safe. Well in the meantime, other people came and rented that space where we had our store and those people trashed it. They broke into the closet even though the landlord told them not to. The Amatos apologized but people will do that.

Well, you’ve heard my life story.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on April 11, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida