A century of struggle for Japanese immigrants in Brazil

When I was studying abroad in the United States, I was happy to hear from a student from Brazil that "Japanese people in Brazil make up only 1% of the population, but they account for 10% of university students."

For example, the University of São Paulo is the most difficult university to enter not only in Brazil but in Latin America as a whole, and has produced many Brazilian presidents, yet Japanese-Brazilian students account for 14% of the total.

What made the writer happy was not that Japanese people are talented, but that the Japanese who immigrated to Brazil were also demonstrating the Japanese character of parents devoting themselves to their children, and their children working hard in return.

I myself have had the opportunity to work in Brazil on a business trip once, and I realized that many Japanese employees are serving as executives in companies, and that their sincerity and ability are no less than that of Japanese expatriates. Japanese people are now respected in society in Brazil as well.

I had thought that a typically Japanese success story of parents caring for their children and children repaying their parents' kindness was unfolding on the other side of the world, but after reading Fukasawa Masayuki's "Another Tale of the Winners: 70 Years of Postwar Japanese Immigrants in Brazil," I realized how shallow an understanding this was.

Mr. Fukazawa served as editor-in-chief of the Japanese language newspaper "Nikkei Shimbun" in Sao Paulo for many years, and in this book he introduces many historical facts he collected locally. Through these facts, it becomes clear that the status that Japanese immigrants in Brazil have achieved today is the result of a century of struggle, overcoming many hardships.

And it is in this struggle that we see the essence of being Japanese.

Working away from home

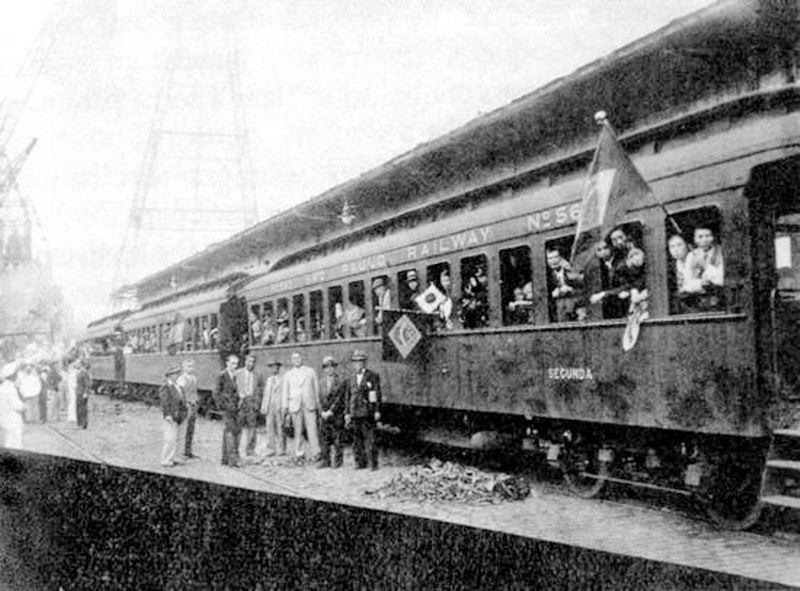

Immigration from Japan to Brazil began in 1908, and totaled 250,000 people before and after the war, with more than half of them, 130,000 people, concentrating in the ten years from 1926 to 1935.

This was due to the economic hardships faced by Japan due to the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 and the Great Depression that lasted from 1930 to the following year, and also due to the fact that the passage of the Japanese Exclusion Act in the United States in 1924 blocked immigration from overseas, and Brazil became a new destination for immigrants.

However, in 1934, the Brazilian government began restricting the entry of Japanese immigrants, and by that time Manchuria had become a new migration destination, causing a sharp decline in immigration to Brazil. It seems that immigration to Brazil was not so much a free choice, but rather a reluctance to seek a new life due to economic hardships at home and the winds of international politics.

Therefore, of the 200,000 pre-war immigrants, 85% came with the intention of working in Brazil for a few years, saving up some money, and then returning home.

The hardships of Japanese immigrants

However, the Brazil that the immigrants arrived in was far from a prosperous and peaceful new world.

He came to Brazil because he was attracted by the fertile land and the promise of earning twice as much as a day laborer in Japan, but even working on a large coffee plantation left him with very little left over after food costs were deducted from his low wages. He was forced to clear the swampland himself and grow rice, but he could barely eat, and during the rainy season mosquitoes swarmed and he was hit by malaria.

Socially, it has been said that "Brazil's elite of the past have always been racist. When Brazil was discovered, the Indians, who were considered an inferior race, were massacred, and black people were treated inhumanly, like animals and commodities. Next, immigrants, especially Asian immigrants, were targeted."

It was a politically unstable country, and in 1924, 6,000 revolutionary troops occupied the city of São Paulo for 20 days, after which 30,000 government troops surrounded them, igniting fierce fighting.

Japanese immigrants, who did not speak the language and had no political power, were scattered across rural areas, and the defeated revolutionary soldiers saw them as ideal prey, attacking and plundering these colonies. The immigrants banded together to defend themselves through gun battles, but many were shot to death.

Even in these difficult times, Japanese language schools were established in each community, and there were close to 500 of them before the war alone. This was probably out of parents' desire to ensure that their children, born in Brazil, would be able to live as normal Japanese people when they returned to Japan.

Japanese immigrants had no choice but to help each other and survive as a community. What supported this community were the "roots" of the Japanese people - diligence, sincerity, and honesty. And by surviving hardship, the roots of the Japanese people may have grown thicker and deeper in the hearts of the immigrants.

Among the successful immigrants were those who worked hard and became owners of large farms, factories, and trading companies.

Oppression of Japanese immigrants

In 1930, Vargas succeeded in staging a military coup and became president. The Vargas dictatorship aimed to boost nationalism in Brazil and banned the study of foreign languages other than Portuguese in primary and secondary education. In 1938, all Japanese language schools in Brazil were closed, and in 1941, all Japanese language newspapers were suspended due to a ban on Japanese language newspapers.

When the Greater East Asian War broke out in December 1941, the assets that Japanese people had built, such as large farms, trading companies, and factories, were seized. The leaders of the Japanese community were arrested and tortured.

In July 1943, a total of five American and Brazilian steamships were sunk by a German submarine off the coast of Santos, the outer port of São Paulo, and Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants were ordered to evacuate the coast of Santos within 24 hours. Japanese immigrants, including women, children, and the elderly, were forced to walk to an immigration camp with only their belongings.

Immigrant painter Tomoo Handa describes the feelings of the people at that time as follows:

There were rumors that many had been arrested by the police, thrown into detention cells, and sometimes even tortured, and the more anxiety grew, the more the vision for the future to escape this situation turned to the "paradise" that was supposedly being constructed within the East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

The immigrants, whose national culture was denied and who were forced to walk in fear every time they left their homes, lost interest in settling in Brazil permanently. The Co-Prosperity Sphere promised by the Japanese military seemed to be the only place they could find meaning in life.

"Another Story of the Winners: 70 Years of Japanese Immigrants in Brazil after the War"

Written by Masayuki Fukazawa / Mumeisha Publishing

*This article was written for the email newsletter "Japan on the Globe: Training Course for International Japanese People," which has 43,000 subscribers and was founded 18 years ago. It was originally published on Mag2NEWS (June 26, 2017) and is reprinted here with permission.

© 2017 Masaomi Ise