The sun was already high in the morning sky when the train slowed to a stop at the Portland Assembly Center north of Oregon’s biggest city.

It was 6 a.m. on June 5, 1942, and 520 Yakima Valley residents of Japanese ancestry had arrived at their home for the next three months.

Hundreds of onlookers watched as families stepped off, children, parents and grandparents, mothers with sleeping babies and sleepy toddlers, women whose husbands had been taken months earlier by authorities. They came from Wapato, Wenatchee and Kennewick with what they could carry when they boarded at dusk the day before.

Some soldiers who traveled with them helped older people off the train as Oregon residents of Japanese ancestry already living in the recently vacated animal stalls unloaded baggage onto the platform.

“The new arrivals ... filed through the gate into the building to register and receive instructions before proceeding to their new quarters,” noted the Friday, June 5, 1942, issue of the Evacuazette, the newsletter created by assembly center residents.

A second train was expected to deliver another 528 residents of Yakima, Toppenish and Wapato on the morning of June 6, followed that afternoon by 100 from Lyle arriving by bus, the newsletter said. That would bring the camp population to about 3,700.

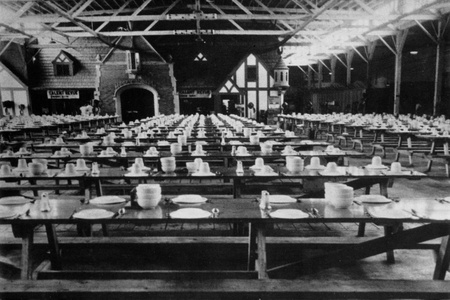

Years later, internees would recall meals in the huge mess hall, mattresses of canvas bags and straw, boredom and physical discomfort. Most of all, though, they remembered the smell of manure wafting through the wooden floorboards — a legacy of the complex built as the Pacific International Livestock Exposition Center.

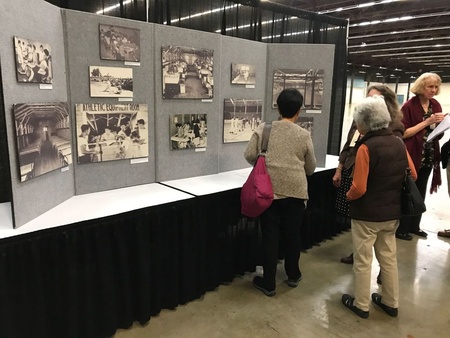

On May 6, some spoke of their experiences at “Return & Remembrance: A Pilgrimage to the Portland Assembly Center,” a special event commemorating the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066 and honoring those it impacted.

Signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942, the order forced approximately 120,000 West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry, many of whom were American citizens, into remote prison camps. That order would eventually include 1,017 Yakima Valley residents.

The livestock exhibition and auction facilities where they were forced to live in the summer of 1942 are gone, replaced by buildings collectively known as the Portland Expo Center. The May event held there by the Oregon Nikkei Endowment and the Portland chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League featured internees’ memories and other speakers, music by the Minidoka Swing Band led by an internee, and a proclamation of apology from Oregon Gov. Kate Brown.

In opening remarks, Lynn Fuchigami Parks, executive director of the Oregon Nikkei Endowment, explained the day’s significance.

“We chose this day — May 6 — because it was on this day 75 years ago that Portland was the first city on the West Coast to be declared free of all Japanese. They had been evacuated here by noon yesterday,” Parks said. The second and final train carrying Valley residents arrived a month later.

“It’s an example of what happens when we let fear and prejudice override our American principles,” she added.

A gate closes

As participants prepared Exhibit Hall A for the afternoon events of May 6, Parks stood in the expansive open space, showing how the current structure fit into the former footprint of the Portland Assembly Center.

“This area was the mess hall. ... The (Evacuazette) office was where the concession stand is. The very end of this space was the men’s dorm,” she said.

The Portland Expo Center is the state’s biggest multi-purpose facility. The 53-acre campus off Interstate 5 between downtown Portland and Vancouver, Wash., includes five large exhibit halls and 10 meeting rooms.

Visitors who arrive on the MAX Light Rail stop see “Torii Gate,” created by Portland artist Valerie Otani to honor internees. Small metal tags — replicas of IDs worn by every camp resident — dangle from its tall timber framework.

A teenage Kara Kondo, then Kara Matsushita, never forgot the sound of the gate door clanging shut behind her as she and her family walked into the assembly center.

In testimony to the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in September 1981, Kondo recalled the evening they left Wapato. She had volunteered to help an Army corporal pronounce Japanese names as families boarded the special Northern Pacific Railroad train in the deepening darkness.

“I looked around. The crowd had grown. People in twos and threes, or huddled in small crowds greeting each other or talking among themselves,” she wrote. “Others walked up and down the length of the 11 coaches searching for friends for some last goodbyes.”

The corporal was among several members of special military intelligence who came from Fort Lewis to process the evacuees. Residents of Japanese ancestry had met them on May 31, when they reported to the Wapato Junior High School gymnasium for instructions on their removal, Kondo recalled.

“Some of us helped at the process center and we got to know members of the force quite well. They had been professional, cheerful, helpful and kind at all times,” Kondo wrote.

One in particular — Staff Sgt. Nathan Miller, a Jewish teacher from Brooklyn — lightened the mood with funny antics, but his tone turned serious one day.

“Why are you letting them do this to you?” Kondo recalled him asking her. “What do you mean?” she responded. “Taking you away and putting (you) into camps,” he said.

Miller explained that they were well-trained to assess people and situations and make judgments on subversives.

“I see nothing, absolutely nothing that justifies this evacuation. When we go into a community, we check police records, go to school to check on students, and make every assessment as to the nature and character of the people we have to deal with. The Japanese students are tops in their classes. Citizenship is flawless. We couldn’t find any delinquency. There’s nothing on the police records. ... Why are you letting them do this to you?”

She didn’t know what to say.

“Many a night when I was finally alone, I had wept over the same question. Why? Not so much that it was happening to me, but that it was happening at all,” wrote Kondo, who died in 2005 at age 89.

So much to lose

Fukiko Takano cried as FBI agents arrested her father, Bunji, on March 24, 1942 — her 17th birthday. The Takano family operated the Empire Hotel on Yakima Avenue, the largest building on the block that housed Yakima’s bustling Japan Town district.

“My oldest sister had just come (home) from the University of Washington. The FBI was going through our belongings,” recalled Takano, 92, of Des Plaines, Ill. “We didn’t even know that he was being taken and we never knew where he was until we got to the camp.”

Several leaders in the Yakima Valley’s Japanese community had been taken away soon after Pearl Harbor was bombed and all “aliens” had to register as traffic and curfew orders began impacting residents, but they “were led to believe that evacuation would not take place,” Kondo wrote.

Executive Order 9066 allowed authorities to remove Japanese residents from their homes in Military Area No. 1 on the West Coast and detain them “for their own safety” in what they called “relocation camps.” The Yakima Valley was outside Military Area No. 1 so was not initially affected by the executive order, “but the same local forces that had persuaded the state and federal governments to pass restrictive laws in the 1920s prevailed, and the boundaries were moved east to include the Yakima Valley,” notes “Land of Joy and Sorrow: Japanese Pioneers in the Yakima Valley,” an ongoing exhibit at the Yakima Valley Museum.

That occurred despite the heartfelt testimony against that relocation of Wapato residents Dan McDonald and Esther Boyd during a public hearing in Seattle.

“In America as a whole, and in the Yakima Valley as well, there had always been discrimination against the Japanese immigrants. The American Legion posts sponsored a Ku Klux Klan rally targeting the Japanese. The Wapato Independent ran anti-Japanese articles and editorials,” the museum exhibit notes.

Rumors of evacuation persisted amid “steadily growing hostility of the community as a whole,” Kondo wrote. “In the groundswell that called for removal of the Japanese, it became difficult to distinguish who (was) friend or foe.”

After Roosevelt signed the executive order, Gen. John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, issued 108 orders removing all Japanese Americans in California, Washington, Oregon, and parts of Arizona from late March to August, according to www.densho.org.

He issued the formal Notice for Exclusion and Instructions No. 98 — which impacted much of Central Washington — on May 26, 1942.

“They didn’t give us much time to get rid of our stuff,” Takano said. “...The building was sold. We were lucky we got out with our possessions. We had a lot of stuff stored with the government and somebody ransacked the warehouse and stole all the artifacts, all of those collections.”

That included the doll collection she displayed on Hina Matsuri, also called Doll Festival or Girls’ Day, which is celebrated on March 3.

“Some of the dolls were real art pieces that were given to us by family in Seattle,” Takano said.

Family traditions disappeared at the Portland Assembly Center, noted David Ono, master of ceremonies on May 6. Ono, the co-anchor for ABC7 Eyewitness News in Los Angeles at 4 and 6 p.m., co-produced “The Legacy of Heart Mountain,” an Emmy Award-winning documentary.

“Families didn’t eat together anymore,” he said. “The family unit really started to break down in these camps.”

George Nakata, detained at the assembly center before he and his family were taken to Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho, spoke of “a home of horse stalls, pig pens. Our unit was 14 by 19 (feet), with plywood walls,” he said.

“The lights went out at 10 p.m. ... We lined up for everything,” added Nakata, who wore a yellow ribbon along with other internees honored on May 6.

Jim Tsugawa remembered mushy oatmeal, fly strips black with flies, losing weight because of illness and a visit from a Caucasian friend.

“There’s Evan, there’s me and there’s that barbed-wire fence,” he said.

During that hot, hot summer before the approximately 3,700 residents of the Portland Assembly Center left for Minidoka and Heart Mountain in late August, couples married, children were born and a boy died from complications of the measles. And they could hear every single thing happening in the converted animal stalls around them, but they endured with patience.

“We lost our businesses. We lost our homes. We lost family heirlooms. We lost our pets. We lost friends,” Nakata said. “But we did not lose our dignity.”

*This article was originally published by the Yakima Herald-Republic on June 3, 2017.

© 2017 Tammy Ayer