My grandmother Kazuko Kuwabara passed away recently, and I can’t help but feel that a piece of history died with her. She was the only one left in my family who knew first-hand the facts surrounding United States vs. Masaaki Kuwabara, one of only two civil rights cases ruled in favor of Japanese Americans during WWII.

You see, Masaaki Kuwabara was her husband—and my grandfather—and he never talked about the court case during his lifetime.

It never occurred to my grandmother to talk about it either until my sister and I started to ask. We were flipping through some books our mother had purchased at a Tule Lake Pilgrimage when we stumbled upon the name of the court case, over a decade after my grandfather had passed away.

While “Masaaki Kuwabara” is not a common name, it was hard for us to believe that the named defendant could really be our grandfather. Surely, we thought—if this were really him—he would have at least mentioned his involvement.

When we finally broached the topic with our grandmother, her response was shockingly nonchalant. Peering up briefly from her newspaper, she said casually, “Why, yes, now that you mention it, I do recall something about a court case.”

Our jaws dropped.

We raced off to the UCLA Law Library, still in disbelief that this was really our grandfather but hungry to know for sure. Our audible gasps echoed through the library when we located the ruling, which included a short biography of the defendant and left no further doubt.

But this newfound clarity only spawned more questions. Our grandparents were like second parents to us: we spent every afternoon together after school. Why didn’t he tell us about this case? What else hadn’t he told us?

How was it possible that we didn’t know about this major event in his life?

The irony is that I had spent so much time speaking with other families about their wartime experiences through a variety of oral history projects like the REgenerations Oral History Project. I even helped to direct Completing the Story, a photo-documentary oral history project of the postwar resettlement experience in Santa Clara Valley.

But I never probed deeper into my own family’s story.

In part, that was because my grandparents were not very forthcoming. I remember asking my grandfather about the internment after school one day, as we were both in the backyard taking care of our pet finches. His response was as matter-of-fact as it was curt: “America is the greatest country on earth,” he replied, “and that’s all you need to know.”

My grandmother would share even less, often responding, “What is there to say?”

But the other reason it never occurred to me to probe deeper was that I grew up hearing a certain narrative about the internment.

This narrative was so prevalent that I never questioned whether my family’s own experience might deviate from it.

In fact, when I started working on the REgenerations Oral History Project, the sole focus was the experience of postwar resettlement. We were told the resettlement era was the only remaining gap in the historical record that needed to be filled. By contrast, the experience of the internment itself was assumed to be known and well-documented.

That internment narrative went something like this.

After the United States declared war against Japan, over 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry residing along the West Coast—two thirds of whom were American-born citizens—were evicted from their homes and sent to internment camps, their only crime being their race.

With only a few notable examples of resistance, like those of Gordon Hirabayashi and Fred Korematsu, the vast majority of Japanese Americans went along with these evacuation orders willingly… their cooperation a sign of their loyalty to America.

Not only did they willingly comply, military-aged men were so eager to prove their loyalty that they volunteered to serve in the U.S. Army. They formed the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which would go on to suffer more casualties than any other unit and become the most decorated combat team of the war for its size and length of service.

It was a narrative I have always felt great ambivalence towards.

Were there really no widespread acts of civil disobedience during this time?

Since when was compliance with injustice synonymous with patriotism?

If the rights of American citizens are supposed to be self-evident and inalienable, why did Japanese Americans feel their loyalty was something that had to be proven rather than presumed?

After being stripped of their most basic civil rights, why did Japanese American men feel compelled to join the military—a racially segregated unit at that—which just several years earlier had expelled them from their ranks as “alien enemies,” even if they were native-born citizens?

And where was the outrage that these soldiers’ families remained behind barbed wire, even as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was sent into the most dangerous theaters of war, often sacrificing their lives to save others? Were Japanese American lives deemed more expendable?

Imagine my surprise, then, when I discovered how different my family’s story was from the narrative I had grown up hearing my whole life.

Through long conversations with my grandmother and family friends, and through countless hours combing through historical documents at the National Archives, I learned that my great-grandfather was hauled away by the FBI in a midnight raid several months prior to the mass evacuation.

Because he was a first-generation (Issei) Japanese fisherman with a short-wave radio, he was considered to be a national security risk and was detained in a Department of Justice camp in New Mexico as an “enemy alien.”

At that time, discriminatory immigration laws did not permit immigrants from Asia to become naturalized as American citizens. But ironically, my great-grandfather enjoyed greater protections as an “enemy alien” under the Geneva Convention than the rest of my family as U.S. citizens under the Constitution.

While my great-grandfather was held in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the rest of the family was taken from their homes in Terminal Island, California and confined thousands of miles away in Jerome, Arkansas.

They would not be reunited for nearly two years, when they were uprooted yet again and re-confined as “trouble makers” at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in California. Until then, being the eldest son, my grandfather would have to assume the role of family patriarch, charged with keeping the family together… a heavy responsibility for someone only 29 years old.

The courage to resist and take a stand against gross injustice

I learned that my grandfather had registered for the U.S. military prior to the war, only to suffer the humiliation of being expelled after the onset of war simply because of his Japanese ancestry.

I beamed with pride upon discovering that when the draft was re-instituted just a few years later, my grandfather had the wherewithal to recognize when enough was enough and the courage to resist the draft until his civil liberties—and those of his family—were restored.

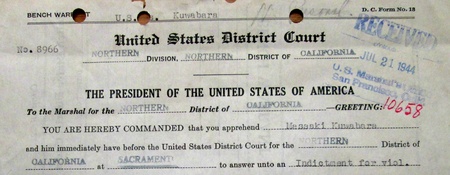

For taking this principled stand, my grandfather was arrested and jailed in Eureka, California, to await trial as the lead defendant in a class action case together with 26 other young men. In Eureka, he had the good fortune of having his case come before Judge Louis E. Goodman, who ruled in my grandfather’s favor.

“It is shocking to the conscience,” Judge Goodman declared, “that an American citizen be confined on the grounds of disloyalty, and then, while so under duress and restraint be compelled to serve in the armed forces, or be prosecuted for not yielding to such compulsion.”

I learned that Judge Goodman, acutely aware of how unpopular his ruling would be and fearing for his safety, kept his car running in the back of the courthouse so that he could make a quick escape as soon as he delivered his judgment.

I also learned that Judge Goodman—surely one of the most notable of unsung heroes in this chapter of American history—would emerge as the only judge to find in favor of Japanese Americans at this time. In contrast, hundreds of other men just like my grandfather would not be so lucky and would be sentenced to multiple years in jail just for standing up for their civil rights.

These are just a few of the things I have learned from my research so far, and the deeper I dig, the more I seem to uncover.

I learned, for example, that United States vs. Masaaki Kuwabara was only the first civil rights case my grandfather was involved in. The second case would take place more than 10 years after the war ended… and presided over once again by Judge Goodman.

Coincidence?

In fact, the only thing I have found more remarkable than my family’s story itself is the fact that my grandparents never mentioned it.

Why, for that matter, does the prevailing narrative of the internment leave out stories of valor like these?

What other untold stories and unsung heroes are missing from that narrative?

What secrets may be lurking within your own families that would make our community’s story richer, more accurate, and more complete?

And why does the Japanese American community not openly talk about them?

Now that both of my grandparents have passed away, I need your help to give voice to this silence.

Perhaps you are an expert in this field—or know people who are—and would be willing to talk with me. Maybe you knew my grandfather? Or maybe you were one of the 26 other defendants who stood trial with him (or, like me, one of their grandchildren)?

Over the next few months, I will be sharing posts about the archival evidence I have found, including the list of other defendants involved in this court case.

Please join me on my quest to piece together the full story my grandparents never felt they could tell me—and unravel the mystery of why they felt they should not tell me—by signing up for my mailing list at http://tinyurl.com/USvsMK-MailingList.

And please get in touch with any questions, suggestions and leads you may have at USvsMK@gmail.com.

* A version of this article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of the Newsletter of the Japanese American Museum of San Jose.

© 2017 Karen Matsuoka