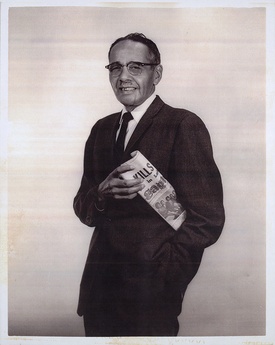

Loren Miller (1903-1967), an African American attorney and newspaperman from Los Angeles, worked to build American democracy during a career that spanned almost 40 years. Although Miller worked with the National Lawyers Guild and numerous other organizations, he made his most lasting contributions as a civil rights lawyer during the 1930s and 1940s, in association with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the American Civil Liberties Union. However, in addition to his primary work on behalf of African Americans, Miller’s efforts as a defender of Japanese Americans deserve extended study.

Born in Nebraska and raised in Kansas, Loren Miller arrived in California in 1930, after his graduation from Washburn College of Law in Topeka, KS. Despite the privations of the Great Depression, he launched a successful law practice in Los Angeles’s growing black community (one of his senior colleagues was Hugh E. Macbeth, who would distinguish himself as an outstanding wartime defender of Japanese Americans). Miller’s activism was not restricted to legal matters, but also extended to journalism and writing. Beginning almost from his arrival in Los Angeles in 1930, Miller remained a regular contributor to the local African American weekly California Eagle, and also served as city editor. He also assisted his cousin Leon Washington in launching a rival newspaper, the Los Angeles Sentinel and produced articles for journals such as The Crisis and The Nation. Miller likewise wrote poetry and moved in literary circles--after visiting the USSR with his close friend Langston Hughes in 1932, he coedited an anthology of Russian-language translations of American Negro poetry. Miller subsequently joined the left-wing League of American Writers.

During World War II, Miller became a nationally recognized specialist in the field of housing discrimination and the law—especially restrictive residential covenants—private agreements not to lease or sell houses to minority groups. These agreements closed off much of urban areas to nonwhite residents and led to overpopulated ghettoes. In the 1944 case Fairchild v Raines and the 1945 “Sugar Hill” case, Miller brought the first successful legal challenges to the use of restrictive covenants against African Americans. As a result, national NAACP counsel Thurgood Marshall invited Miller to join the NAACP’s legal team. Miller served as NAACP Chief Counsel in Shelley v. Kraemer, the landmark 1948 Supreme Court case in which the Court struck down legal enforcement of restrictive covenants as unconstitutional. Not only was the case a blow against housing discrimination, but the court’s decision, and the reasoning behind it, served as a major precedent for the Brown v. Board of Education case six years later. After the victory in Shelley, Miller was named head of the NAACP’s West Coast Regional Legal Committee, where he continued to fight housing segregation and employment discrimination cases. He also served as counsel in the landmark 1948 Perez v. Sharp case, which struck down California’s laws against interracial marriage.

At the same time, he distinguished himself as a defender of Japanese Americans in the face of widespread wartime hostility against them. His first major contact with Japanese Americans was in the 1943 federal court case of Regan v. King, in which white nativists sued to strip Americans of Japanese ancestry of their citizenship rights. Miller signed the ACLU’s friend of the court brief. He also signed the habeas corpus petition of Ernest Kinzo and Toki Wakayama, a husband and wife pair of Nisei who in mid-1942 challenged their confinement under Executive Order 9066 but whose petition remained dormant for many months. In the years after World War II, Miller worked to ensure harmonious relations between Japanese Americans returning to Los Angeles and their black neighbors. He stated in 1948 that relations between the two groups in areas such as Little Tokyo/Bronzeville were not tense. Though young “hoodlums” had harassed older residents and some Japaense American merchants had hired private guards, none of this was of importance.

During this period, Miller joined with Japanese American Citizens League counsel A.L. Wirin to build an effective alliance for civil rights. The two achieved unprecedented gains. Miller was of counsel on People v. Oyama, the case that challenged escheat suits to take land away from Japanese American owners. The case climaxed in the notable 1948 Supreme Court case Oyama v. California. The Court’s ruling in the case not only struck down alien land laws, but also established the Court’s doctrine of “strict scrutiny” of racial classifications. Miller also served as counsel when Wirin challenged discriminatory statewide Alien Fishing License legislation in Takahashi v. California Fish and Game Commission. The case led to another landmark Supreme Court case, which forever banned legal discrimination against so-called “aliens ineligible to citizenship.” Meanwhile, on behalf of the JACL, the two attorneys brought suit in Amer v. Superior Court and Yin Kim v. Superior Court, two cases that challenged restrictive covenants Asian Americans (with, respectively, a Chinese-American and Korean-American plaintiff). After losing the cases in California courts, Miller and Wirin sought an appeal to the United States Supreme Court, on the theory that such cases would help buttress the NAACP case in Shelley v. Kraemer. However, the Court declined to take up the cases before its Shelley ruling, following which it reversed the state court decisions.

In 1951, Loren Miller bought the California Eagle newspaper from longtime editor Charlotta Bass. Under Miller’s direction, the Eagle remained a stalwart voice for civil rights, challenging police brutality, discrimination in city hiring and (of course) housing segregation. Under Miller’s direction, the Eagle also opposed the hysterical anticommunism of the McCarthy era. In later years he also undertook a historical study of the Supreme Court and civil rights. Published in 1966 as The Petitioners, it became a standard reference work. Because of his writing and journalistic responsibilities, he reduced his legal work, though in 1956 he was appointed to the National NAACP Board of Directors.

Miller retained his connection with Japanese American communities. He collaborated with JACL activists on panels to further Equal Employment Opportunity. His children attended the Nisei church school of the Hollywood (Japanese) Independent Church. He was thus greatly disappointed in 1963 when Hokubei Mainichi editor Howard Imazeki produced an editorial opposing civil rights legislation and suggesting that African Americans organize to improve conditions in their own communities. In a letter to the newspaper Miller complained that Imazeki had been “brainwashed” and reminded readers that blacks had not openly opposed mass confinement in significant numbers, but had been of great service to Nisei in breaking down restrictive covenants and laws banning interracial marriage, and had urged Congress to support citizenship for Japanese aliens.

In tribute to his civil rights record, in 1958 Miller was appointed executive clemency secretary by California governor Edmund “Pat” Brown. After the nomination was challenged on the basis of Miller’s alleged “subversive” activities, he was forced to withdraw his name. However, in 1964 Miller was appointed by Brown as a California Superior Court Judge. He served only a short time before his untimely death. In 1977 the California Bar Association created the Loren Miller Legal Services Award to honor attorneys who have demonstrated a long-term commitment to public service. In San Francisco he is honored by the naming of the Loren Miller homes, a housing development.

© 2017 Greg Robinson