The grandfather of my heart will always be my father’s father, Grandfather Araki (born a Kaneda but taking the Araki name as a yoshi), whom I called Jichan. He gave me the precious gift of unconditional love. I thought Jichan was his given name. In reality, it was a child’s version of ojisan, which means “old man” or “grandfather” in Japanese. Jichan’s true given name was Nisaku.

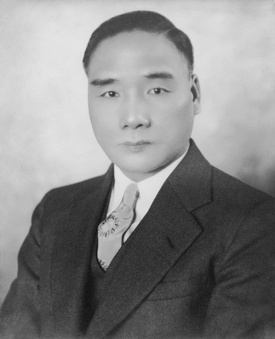

Grandfather asked me once why I called him Jichan. I told him all my friends’ names ended in chan and since he was my friend, I had added chan to his name too. Jichan smiled delightedly at my answer, giving me a warm, broad grin of approval and deep chuckle. I can see him in that moment, bending down to look at my face, hands on his knees. Jichan’s wide, square face with handsome thick black eyebrows, an inelegant snub nose and a broad, high forehead, accentuated by a receding hairline, smiling down at me. He bent down even lower to let me climb on his back to give me an ombu (piggyback) ride. Though behind barbed wire in Camp Minidoka, I felt safe and secure on his broad back, on top of the world.

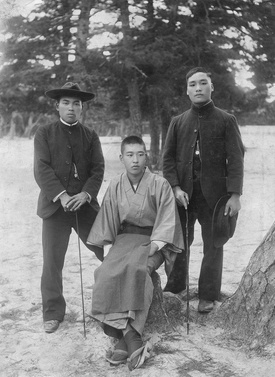

When Jichan entered the U.S. by way of Canada in 1906, he was about 20 years old. Chachan, or Shinsaku Kaneda, Jichan’s older brother, entered the U.S. a few months after Jichan and they often worked together. One of Jichan’s and Chachan’s first American adventures must have occurred between 1906, the year of Jichan’s arrival in America and 1909, the year of his employment at the Seattle Rainier Club on San Juan Island. It is the main island of a group of islands we called “the San Juans”, located close to Canada in Washington State,explored by Russians, Spanish and British, seeking the fabled Northwest Passage linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

One day, around the family dinner table, I asked Mom about Jichan’s job at McMillin’s Roche Harbor site on San Juan Island. Mother said, that Jichan was a gardener and she smilingly hummed a tune and pantomimed daintily watering plants, saying that Jichan always seemed to get the easy jobs. Of course, Mother and I knew that gardening is backbreaking work. Still Chachan’s work was even more physically demanding than Jichan’s gardening job. According to Dad, Chachan moved heavy barrels of lime on the Roche Harbor dock. Dad said that Chachan was, though wiry and “… a little guy,” very strong and proud, even arrogant, about his strength. Later I read that those limestone barrels that Chachan moved weighed two hundred pounds!

Mother called Chachan’s foreman a Simon Legree. Mom’s version of Jichan’s and Chachan’s San Juan Island experience, like something out of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was probably inaccurate in specific details. However, I am certain Mom accurately conveyed how Jichan and Chachan felt about their Roche Harbor experience and Chachan’s foreman.

Mother was especially clear about the Japanese graves she had seen in the Roche Harbor Graveyard. She recalled what she’d read on the graveyard headstones with Japanese names and the ages of the dead young men who died in their teens and early twenties of diseases like consumption, pneumonia, broken limbs or fevers. The graves had stacked large stones in Japanese style. But I could not find them when I visited the graveyard around 1998. Inquiring about the missing headstones, I learned that most laborers’ graves had been moved. The McMillin family mausoleum, a graceful and beautiful white limestone structure on the National Register of Historic Places, dominates the Roche Harbor Graveyard today as in the past.

All the workers were housed in McMillin properties and paid rent to the company for their living quarters. On a 1998 visit, one of the Friday Harbor locals told me that Jichan and Chachan must have lived in the long gone Jap Town – the term used in the National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination form for that section of Roche Harbor where household domestic servants were housed. Another of the San Juan Island locals told me that each nationality got a certain kind of job and that only Chinks did fish processing while only Filipinos did housework. The casualness with which the locals of Friday Harbor used offensive terms like Jap and Chink startled me. I decided that they meant no offense but were simply using names that had been long accepted as part of the local custom.

If Jap Town was accurately named and used to house domestic servants, then housework was not reserved for Filipinos only. Apparently most domestic servants were Japanese or Japanese-American. I cannot verify that only Chinese workers processed fish. However, an old tradition of smuggling, including the smuggling of Chinese laborers and opium, existed throughout the islands. There were undoubtedly Chinese workers on San Juan Island at the time when Jichan and Chachan worked there. Because Richard Walker, author of Images of America: Roche Harbor recalls a piece of fish processing machinery call the “iron Chink” it’s likely that most fish processing was done by Chinese.

What is certain is that Chachan had a falling out with his white boss and was summarily fired. Because Jichan was the brother of a fired worker, Jichan was fired too. Being fired simply didn’t occur in the Japan of that time and would normally be very shameful. But in the family lore, Jichan and Chachan were well justified in leaving. Raised with traditional Japanese respect for authority, it would have taken a very unfairly abusive foreman to cause Chachan to speak out. I rather imagine he might have flung a Japanese epithet at the foreman. Whatever Chachan said, he made his anger clear to the foreman. Jichan and Chachan had to walk the ten miles from the company town of Roche Harbor to Friday Harbor, where they could catch a boat back to the mainland.

I can picture the two brothers, striding along the long dirt road toward Friday Harbor, through thick evergreen forests, the spicy smell of damp blackberry leaves floating in the air. Jichan stood about five-foot-five-inches tall with broad, muscular shoulders. He’d always had a stocky build and he developed a very muscular physique cutting trees in logging camps and working on the railroad. Chachan, the same height or slightly shorter than Jichan, was thin, with a wiry build, but Chachan was the stronger of the two. Both carried their belongings on their backs, speaking Japanese to one another and laughing aloud, Chachan with a swagger in his walk. I can almost hear the choice Japanese swear words they used to describe the foreman who had fired them. Their laughter and proud, defiant spirits ring down through the years and their laughter, passed down in the family lore is heard to the present day.

© 2017 Susan Yamamura