The generation born between the 1980s and the early 2000s is called the "millennials." Those born and raised during Japan's bubble economy (December 1986 to February 1991) are undoubtedly millennials, but in addition, those who are graduating from high school or university in 2017 also fall into this category. They are a generation born into this generation. How to manage this new generation of young people, how to develop them as human resources useful to society or the company, and how to understand their needs and capture that market are major challenges for companies. Companies are exploring how to appeal to the millennial generation as a workforce and market, governments as taxpayers, and politics as voters. Since 2000, the millennial generation has been attracting attention socially, especially in developed countries, and numerous studies are being conducted at universities and private think tanks.

I have observed the millennial generation every time young Japanese descendants from Latin America come to Japan for study or training. Of course, there are differences between young people in developed countries like Japan and those in emerging or developing countries like Latin America, but there are also many things they have in common. JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) has been running the Latin American Japanese Community Youth and Senior Volunteer Program1 for a long time, and in recent years the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been running the "Juntos!! Latin American Exchange Program to Promote Understanding of Japan" 2 exchange program with Latin American Japanese communities. However, if you are targeting local young people or those in their early twenties, you first need to know more about Japan's millennial generation.

There are many criticisms and assessments of this millennial generation. Feature articles from Spain and South American countries3 have described them as "a lazy generation that only does things that interest them", "many of them are selfish because they were raised in an overprotected environment", "they have been blessed and spoiled, so they have a lot of selfish tendencies", "weak and herbivorous (very kind)", "they have high ideals, but only associate with others through empathy", "if they have a sense of purpose and empathetic values, they tend to become close with people they have never met on social media", "young people who are good at languages make friends all over the world, but that world is surprisingly small", "they tend to quickly lose interest in things, so even if they do join a club, they will soon leave", "they tend not to belong to any particular political or religious organization, and so are tolerant", "they value different cultures and diversity, but when it becomes too much of a hassle, they don't try to understand them head-on and will leave the group", "they prefer things that are visually appealing, and are not very interested in things that are not. "They generally do not like wasteful spending and only buy things that they can sympathize with or that they absolutely want", "They are not particularly interested in owning a home or a car, especially expensive ones", "Many young people believe that the current (globalized) world economy has enriched only a few people in the financial industry and those in power, and has created enormous inequality", "Even though they are from a different generation than themselves, they have a strong tendency to support leaders who speak out against such inequality and injustice (such as US Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders)", "They have a vague feeling ever since they were students that even if they study hard (at university, etc.) as their parents nagging them to do, they will not be able to get a good job and will not be able to pay off their student loans after graduation", "They value the present, cherish friends who they can sympathize with, and feel that they cannot rely much on the government or social systems", and so on.

Although it is a general theory, there are surely some parts that people who are in contact with students or working people in their 20s can agree with. However, much of it falls under the "image of young people" that has been circulating since the time when humans began to act in groups, and has remained the same in any era. New elements unique to the millennial generation are how they deal with digital information and the era in which "emotions" can be transmitted instantly anywhere in the world. However, it is important to remember that just because you empathize with something does not mean that the actual problem will be solved. Sharing a problem does not lead to a solution, but depending on the time and situation, it is possible to get many people to empathize, and as a result, it may be possible to encourage even a small amount of positive change.

Japanese trainees and international students from Latin America, especially the younger generation, have these elements, and while they learn a lot of things obediently, they are also sensitive and sometimes feel that they lack a core. Even though they may seem quiet, they are proactive on the Internet, and when you ask them to write their impressions on paper in class, they sometimes make surprisingly strong points and assertions. They also like being right and idealistic, and hate distorted things such as black companies and inequality, which are currently social problems. Perhaps they do not participate in large rallies and protest like in the 1960s, but they may make clear statements on social media, or simply ignore such issues. They move away from things they dislike without feeling any gratitude or ties. They do not place much importance on the "lifestyles" and "values" that the previous generation and the generation before that used to "model" them, and they seem to be quite self-paced. I quite like that about them, and when I try to talk from a perspective that is not bound by stereotypes, by talking from a South American perspective in Japan, and from a Japanese perspective in South America, people tend to listen with a fair amount of interest.

Although they are called the Internet generation, they are not immersed in a fantasy world. Rather, they are very realistic in their search for answers, wanting to know the reality and possible choices. Their weaknesses are that they sometimes oversimplify things and are too impatient. They shy away from pretty words and are quite suspicious of political messages, whether left or right, which seems to lead to them becoming detached from politics. Either way, they seek answers that are too extreme, which may be dangerous.

One interesting difference is that when I ask millennials in my university classes, "What would you do if you had more income?" Japanese students often give the cautious answer, "I would save for my retirement." However, South American millennials stand out in their response, "I would use it to enjoy myself now." However, what is common to Japanese and Latin American millennials is that this generation will make donations and engage in volunteer work even if they don't have much income. Online donations by purpose (business) are a good example of this, 4 and it is said that volunteers who go to disaster sites gather where there is a solid reception system and their roles have been defined to a certain extent in advance.

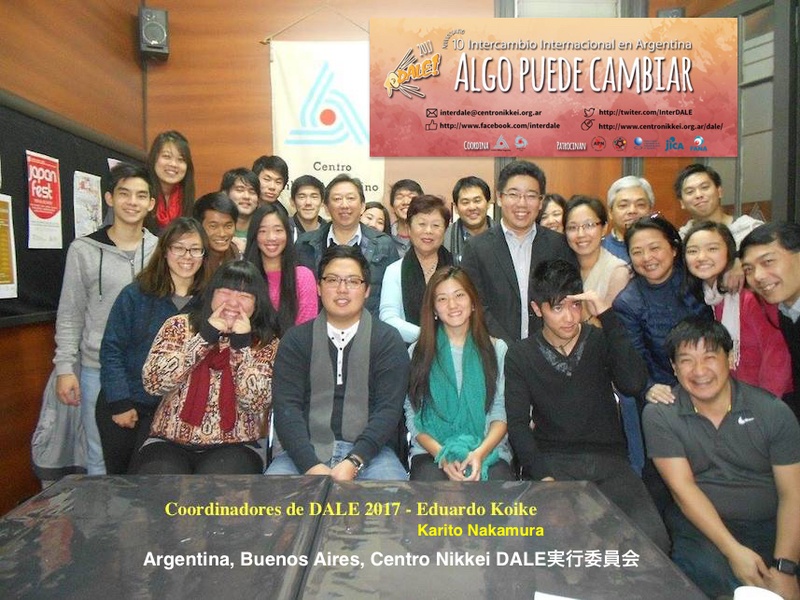

Also, the millennial generation's style is to reach a consensus and do something together. That's why, even in the case of the Japanese junior youth training camps held in South America (Dale (Argentina), Lidercambio (Peru), Vibra Joven (Mexico), etc.), a lot of time is spent preparing under the guidance of seniors, making it easy for participants to participate, developing their sensitivities while having fun, and making efforts to make it possible for them to feel fulfilled. And when it comes to raising a problem, the aim is not just to think about what they have in common, but also to increase each person's self-esteem. This process allows introverted young people to rediscover themselves and strengthens unity within the group. It also naturally develops leaders and trains them to work in groups. However, this does not necessarily lead to a solid sense of belonging to the organization or group, and if people get bored, they will quickly leave.

However, before complaining about "young people today!", we need to get closer to the current millennial generation and search together for answers to various issues. If we value this process, I'm sure we will be able to build trust between generations.

Notes:

1. What is JICA's overseas volunteer program? >>

2. Juntos!! Latin America and the Caribbean Exchange to Promote Understanding of Japan >>

3. Carolina Mila, ¿ Is there a generation of resources? UPSOCL, 2015.

Luján Scarpinelli, The Millennials and the Dinner: A time and an inversion of a generation with many objectives and poor quality results, La Nación, 2016.05.09.

Sanae Akiyama, The world is entering an era where the millennial generation's "desire for self-exhibitionism" will shake up society, "WIRED" 2014.10.13

2016 Deloitte Millennial Annual Survey : "Attracting the Next Generation of Leaders"

4. Fundraising allows you to make donations for specific purposes and projects, and you can also follow up on the results.

© 2017 Alberto J. Matsumoto