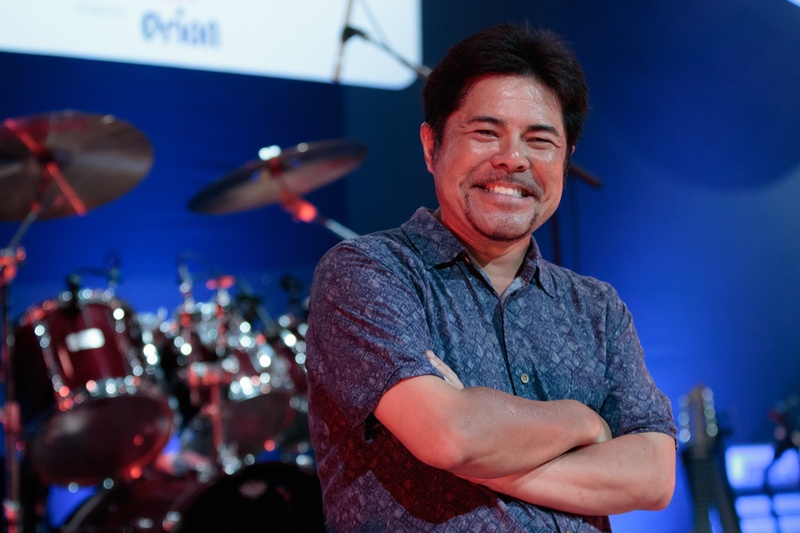

Beto Shiroma shakes his hand tightly. He seems to be full of energy, as if the day had just begun, although night has almost fallen when the interview takes place and he has easily had a hectic day, like every time he arrives in Peru.

It's paradoxical: he has a busy schedule in Peru, he goes from here to there, they call him from everywhere, so in theory he should be tired; However, it is as if the hustle injects energy into him. Peru exerts a notable influence on him. He has already said it before: here he recharges his batteries.

“It happens to me all the time. I get off the plane, breathe the air of Peru and it's as if the entire Inca empire was inside you (laughs). It has no explanation, it's something mental perhaps. When I come here, in the short time I am here I have to do many things, but even so I am recharging myself.”

STARTING FROM SCRATCH IN OKINAWA

He went to Japan in 1986. He was 20 years old. A year earlier he had won a Pan-American Nikkei singing contest and the prize was a ticket to Japan. “It was like winning the lottery,” he remembers. The dekasegi phenomenon had not yet begun.

In Tokyo she tried to carve out a career as an enka singer, but found no open doors. To do? Where to go? Providentially, Okinawa appeared as an exit, where he made his way from below.

He worked in restaurants to make a living, got opportunities to sing and slowly made a name for himself as a singer. He never imagined that performing songs like “Bésame mucho” or “La bamba” would give him something to eat. “The Condor Passes” opened many doors for him.

His first job as a musician was in a restaurant: three times a week, four performances of 40 minutes each. They asked for “international music.” He sang in English and Spanish, not Japanese. “I was becoming another singer, it wasn't the Beto Shiroma that everyone knew.”

They called him from various places. In one of those places, a hotel, guitar in hand, he sang without a microphone from table to table. There was a stage, but it wasn't for him. Still. His opportunity came when the group that was scheduled to perform at the hotel during the summer season canceled.

The show promoter asked him to replace them. Of course, with one condition: that two musicians accompany him. Beto barely had two weeks not only to find them, but also to prepare a show with about twenty songs.

He recruited two musicians (one of them bassist Tom Nakasone) and with them formed the trio Diamantes. They performed pieces in Spanish such as “Cielito Lindo” and songs by the Beatles.

He was doing well, but he wasn't satisfied. “We have to do something else,” he told himself. Thus was born his first song, “Okinawa, mi amor”, but only to sing at the hotel, not to be recorded.

Diamantes incorporated other musicians, including a guitarist who accentuated the rock side of the group. If in the hotel they sang “Bésame mucho”, in another place they covered Santana. Boleros, pop and rock, they oscillated between various genres until their first hit would arrive.

GOLDEN OPPORTUNITY

Beto Shiroma did not coin the term “Gambateando”, but he made it music. The song became a kind of anthem for many Peruvians who worked hard in Japan's factories in the early 1990s.

“If I don't do the song, who is going to do it. We had to make that song because everyone came with fatigue, with the hustle and bustle, with the mistreatment. They were mistreated and that made me angry. How are you going to be treated like this because you are a dekasegi and don't speak Japanese? 'No,' I said. They looked for lawsuits against them, they discriminated against them. Because of that letter, many Japanese feel a little bad, but it's true. I felt like that. If I don't say it, who is going to say it. Identifying with a song for me at that time was important. I never worked in a factory, but my father was working in a factory, my uncle, my cousins, my friends.”

Although the song crudely refers to the situation of the dekasegi (“Apart from the routine / endless and heavy / there are people who discriminate / and provoke him for nothing”) it is not pitiful nor does it seek to victimize him. It is a call to resistance, not with resentment or bad grapes, but with tropical vigor.

"Latin music is like that, you sing the sad things and (say), 'yes, what are we going to do, we have to keep living, I'm alive.'"

Beto was inspired to create “Gambateando” by the author of classics such as “Decisiones”, “Plástica” and “Pedro Navaja”. Pieces to dance and listen to, with a message. “My teacher is Rubén Blades,” he says.

When the group recorded “Gambateando”, a golden opportunity arose: the Orion brewery asked them for a song for a commercial. That was the only one they had and they gave it to him. It was a success. Diamonds took off.

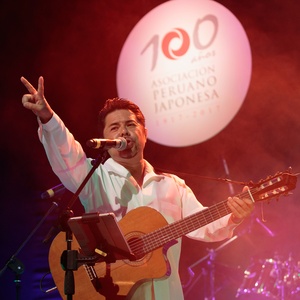

Beto Shiroma returned to Peru eight years after emigrating to Japan. He came with his group and accompanied by media such as NHK. He was already a recognized figure.

“The airport was a madhouse, it seemed like the team was returning after winning a World Cup, it was like a dream. The choir of the Nisei Callao Association, the Sakura club, the La Unión Stadium, the Minors Movement, with their banners, all the places where I had participated were waiting for me. It seemed like a superstar was coming. “It was really exciting.”

Despite the distance and the time that has passed, Beto's relationship with the Nikkei community in Peru has not lost feeling. The musician, who defines his work as “making people happy,” says that he still finds people who ask him for the songs he sang more than thirty years ago, before traveling to Japan. “It makes me laugh, but it also fills me with nostalgia and joy.”

A “PROCESS” FOR THOSE WHO COME

For Beto, success is not the lightning, but the candle that never goes out; It is not reaching the top, but keeping climbing. Without lacking modesty he says: “Don't think that we have reached very high levels, more or less... in Okinawa everyone does know us. As an artistic group we have been successful in the sense that we have continued for 25 years, no one can take that away from us.”

That is why he can take pride in the fact that after experiencing so many things, with good times and “shaking moments”, more than a quarter of a century later, they are still there.

2016 was not only special because of Diamantes' silver anniversary, but also because Beto turned 50 years old. Balance time. “How much longer can we continue?” he asked himself. “Let's move forward, I still feel young,” he responded.

Although staying in the race is a merit, for him that is not enough. You have to leave something.

“I don't want to leave this world and have it just stay like this, (I want) to at least leave a process there so that someone can walk, we can leave something behind, I say. Everything you see here right now (the Peruvian Japanese Cultural Center) is that, a legacy, the La Unión Stadium is a great thing, all that our grandparents have done for us, and (I want) to contribute with that.”

DATA

l Beto Shiroma is married to an Okinawan woman. He has three children born in Japan. One of them dances marinera and represented Japan in the national competition held in Trujillo.

l He arrived in Peru to perform in the show Okinawa Latina at the Peruvian Japanese Theater and at the Okinawa Matsuri.

*This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 108, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2017 Asociación Peruano Japonesa