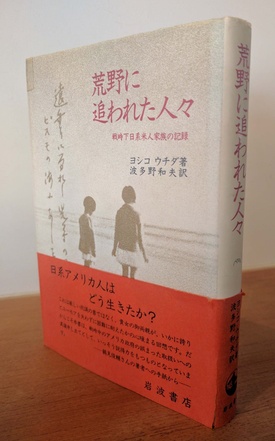

Yoshiko Uchida, a second-generation Japanese-American woman writer, was born in Alameda, California in 1921 (Taisho 10) and grew up in Berkeley. She has written many children's books and has a deep knowledge of Japanese folk art, and in her non-fiction book, Uchida writes about her and her family's experiences in internment camps during the war, titled "People Driven to the Wilderness: Records of a Japanese-American Family in Wartime" (1985, translated by Hatano Kazuo, Iwanami Shoten).

The original title is DESERT EXILE: The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family, and it was published by the University of Washington Press in Seattle in 1982. It is one of many works of fiction and non-fiction written by second-generation Japanese Americans who experienced the internment camps, but it was published 37 years after the end of the war.

At the time this book was written, the U.S. government had finally publicly acknowledged the mistakes of its wartime policies toward Japanese Americans, and preparations were underway to provide compensation to those involved. However, many Issei, like Yoshiko Uchida's parents, had already passed away. And in 1992, almost ten years after the book was published, the author passed away as well.

When she published the book, she wanted young Americans to know the history of Japanese Americans as part of the history of the United States, a country that has built its glorious history through the energy of various immigrants. In the epilogue to the book, she writes the following about how it took so many years for this to finally take shape:

<p... It is not because I did not want to remember our captivity or make this inner journey to my younger self, but because it took a long time for these words to find a place in my life. I am grateful that they have finally found a place.

The author's father grew up in poverty in Japan, but graduated from Doshisha University in Kyoto while working, and then moved to the United States. Her mother also studied at Doshisha while working. The two began to correspond with each other at the urging of teachers at Doshisha who knew each other, and although they never met in person, they married and had two daughters. The younger sister is the author, Yoshiko.

His father became an employee of Mitsui & Co. in San Francisco, and the family of four rented a house in a predominantly white neighborhood in San Francisco. His father worked energetically and was involved in community and church activities, while his mother was considerate and considerate of others, and they integrated into American society. While the family had a Christian spirit of charity, they also valued traditional Japanese culture and customs. Having grown up in this family environment, the author has always respected his parents, who survived in the new world with strictness, honesty, and strength, as well as the Issei of his generation.

When the war began, like other Japanese Americans, he was forced to leave his home and lived in a temporary internment camp that had been used as a stable, and was then sent to the Topaz Internment Camp in the Utah desert. In this book, the author, who was a university student at the time the war began, calmly describes his days from his home to the internment camp, until he eventually left the camp to study at a university in the east on a scholarship.

Here we can see attempts to make life as comfortable and fulfilling as possible in a harsh environment. For example, they desperately try to grow vegetation, such as planting willow seedlings in the desert, although this unfortunately ends in failure.

Also, although not as severe as the "riots" at Manzanar internment camp in California, there were also violent incidents in which pro-Japanese detainees directed their anger at fellow detainees who appeared to be pro-American. Complaints were also made against the author's father, who was seen as pro-white administrative officials. As the detention period dragged on, the detainees began to vent their frustrations on their compatriots.

During his time as a prisoner, the author read books, attended art classes, and watched movies. He also worked as a teacher at a school in the camp, teaching the children with great enthusiasm. However, he is convinced that his freedom was restricted.

Whatever I did, I still belonged to a special society, artificially created by the government, on the periphery of the real world, a dreary, barbed-wire-surrounded camp in the midst of a bleak and unforgiving landscape, with nothing to please the eye or soothe the soul.

On this point, the article quotes the following words from Dillon S. Meyer, who was then the director of camps for the Wartime Relocation Administration:

Segregation stifles the spirit of enterprise, weakens the innate human tendency towards dignity and freedom, and breeds suspicion, anxiety and tension.

The author, a second-generation Japanese, is proud of the first-generation Japanese who endured hardship and survived, and says that their feelings should be passed on to future generations. He emphasizes that enduring the pain of internment and discrimination is something to be proud of, not something to be ashamed of; what should be ashamed of is "our country." And he wrote this book to ensure that such things never happen again.

However, when this book was published in Japan, the feeling that Japan's economic power was threatening America spread, and antipathy toward Japan would rise, which the author feared would manifest itself as antipathy, hostility, and discrimination toward Asians. He was also reminded of the wartime period.

Now, at a time when discrimination and resentment against minorities and immigrants are easily arising, we cannot help but feel that this is a concern that we must continue to hold onto through the ages.

Finally, while many second and third generation Japanese Americans have few opportunities to visit Japan, where their roots lie, the author values his ties with Japan, having spent two years in Japan as a Ford Foundation overseas research fellow and visiting the graves of his ancestors.

"I have climbed remote temple cemeteries in the trees and splashed water on the gravestones of my grandfathers and maternal grandmother to 'revive the spirits of my ancestors'. I have also travelled around the countryside and discovered its incredible beauty," he says.

As a Japanese person, I empathize with his struggle with his dual identities to both America and Japan, while at the same time fully empathizing with the value that comes with that duality.

© 2017 Ryusuke Kawai