Manzanar was one of 10 internment camps built across the United States to segregate Japanese Americans after the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States. It was located in a desolate area in eastern California, with the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the west.

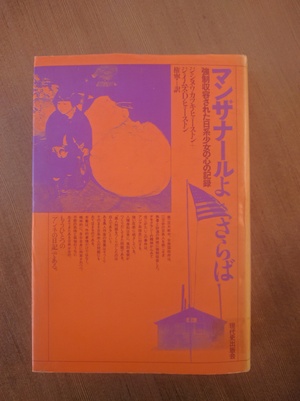

"Farewell to Manzanar: A Heartfelt Record of a Japanese-American Girl Interned" is a non-fiction account of life during and after the war as a Japanese-American, told through the eyes of a girl who spent three and a half years there with her family.

The original title was "Farewell to Manzanar," and it was published simultaneously in the United States and Canada in 1973, and two years later in Japan by the Modern History Research Association, translated by Gon Nei. The authors are listed as the husband and wife duo Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston & James. D. Houston, and the book is a chronicle of Jeanne's experiences and feelings as a young girl.

What is striking is not only the record of life in the internment camp, but also the way in which the film depicts a Japanese-American girl growing up even after the war ends, facing discrimination and prejudice, and her own relationship with race, country, and family, as she questions what Manzanar, her formative experience, is.

Furthermore, the book talks about her father's past as a native of Hiroshima, and how his son (the girl's older brother) went to visit his relatives in Japan after the war. As a record by a Japanese-American author, it is rare for it not to focus on the story within the United States, but to intersect with her roots overseas, and the skillful depictions of these scenes make it a memorable read.

Born to a first-generation Japanese immigrant father and an American-born Japanese mother, she was incarcerated in the camp with her family and spent three and a half years of her childhood there, from the age of seven to 11. After the war began, her father, a fisherman with two boats, was suspected of communicating with the Japanese military, arrested and taken away by the FBI, and interned at Fort Lincoln. Her mother and children were then interned at Manzanar.

The poor quality buildings let in dust from the cracks, the beds packed like sardines, the toilets overflowing with filth, not only was there no privacy, but people still had to wait in line. The girl saw the efforts of these people to change this environment little by little, and as they got used to it, the adults tried to create something to make them feel at least a little more at ease, such as creating a Japanese-style garden.

Eventually, the camp "became a world with its own logic and way of life," and it became like a "small town" with schools, churches, fire brigades, beauty salons, tennis courts, and dance bands.

That said, it was freedom within restrictions, and while they were getting used to this freedom, they also had complex emotions as they had to accept a negative freedom, having to overcome the anxiety of not knowing how Japanese people of war would be treated outside the fence.

Eventually, my father joined me at Manzanar, but he was not the same resolute and reliable father he used to be. My father, who immigrated from Hiroshima, was proud and a typical Japanese patriarch. However, perhaps because he felt powerless, he became addicted to alcohol and sometimes became violent. When anti-American sentiment arose in the camp and escalated into riots, my father was gossiped about as a pro-American "dog."

The government asks the internment campers if they will pledge loyalty to the country in order to recruit volunteers. My father is a Japanese citizen, but he knows that he will have to live in America from now on. He is also afraid that he will be sent back to Japan if he does not pledge loyalty, so he reluctantly answers "yes."

However, he opposes his son's decision to volunteer and say "yes." The father, who feels that fighting itself is meaningless, is exhausted by the intense exchanges with his compatriots in the camp who preach anti-Americanism, and in tears, he hums the national anthem "Kimigayo." The author describes the song he sings at this time as "a patriotic song that can be interpreted as both a proverb and a personal creed of perseverance."

After the war ended, the girl and her family left the camp, but as she grew up, she became aware of the way she was perceived in American society.

"They didn't see me. They saw the slanted corners of the eyes - an Oriental. To some extent this explains why all the Japanese were deported. Only when you no longer see individuals as individuals is it possible to deport 110,000 people."

These words make me realize the danger of viewing people in general terms such as "Muslims" without looking at them as individuals, out of fear of terrorism, a trend that is spreading throughout the world these days.

As a victim of discrimination, the girl wants to erase her existence, but at the same time, she also wants to become a normal American. Through this psychological conflict, she grows into an adult and eventually no longer wants to mention the internment camps.

However, 30 years later, the girl returns to Manzanar with her three children. From this point on, the book is written from the author's perspective. The author realizes that her life began in Manzanar and understands what this place means to her, and is finally able to say "Goodbye, Manzanar."

This book is a fascinating and excellent piece of literary nonfiction, both as a record of a wartime internment camp and as a sensitive chronicle of a young girl's experiences growing up as a foreigner in America.

(Titles omitted)

© 2017 Ryusuke Kawai