So those were hard times. Once I was home for a girls’ meeting and I was intending to take the train back to San Francisco on Monday morning. They wouldn’t allow me to get on the train, they wouldn’t sell me a ticket.

I think I can still picture him. I said, ‘Why not?’ He said, ‘Your country started a war against us.'” And I said that’s not my country. I said I’m an American born, Japanese American. He said, “Doesn’t make any difference, can’t sell you a ticket. If you want a ticket, go to a lawyer and have them write up a birth certificate for you.” You know we had to have proof. And so I called my friends and they happened to be home and they took me to the lawyer’s office. And as I talk about this recently, I completely forgot to pay them the lawyer’s fee, after all these years I didn’t even offer to pay them, they’re both gone now.

But anyway, that didn’t do any good. So I went home, they took me home. And in those days we didn’t have cell phones, and no phones in the house. So it was hard to try and get a ride back to San Francisco. Finally, somebody contacted me and I went with them. But instead of going across the Bay Bridge, we went from Placer through Sacramento, Stockton, San Jose, up that way, so we had no bridge to cross. So that’s how I got back there to finish my studies.

So at the bridge crossing, they would have stopped you?

Oh yeah, they wouldn’t have let us cross. We were enemy aliens, regardless of being American citizens. So then, they dropped me off and I finished my school. The principal was very thoughtful. She says, ’I’m giving you girls your diploma because without a diploma, trying to get a job would be very hard.’ So she gave us our diplomas.

Then we had a hard time because we had to go to the WCCA office. And there were lines down the block, just zigzags. And there were Italians and there were Germans, not that many, but the rest were Japanese. And so we had to get a pass to go home. I went to Sacramento, my brother picked me up. Then they recruited me to go to this grammar school there and tell the people ‘this is what you could take with you when you leave,’ because we were being evacuated. That’s the one reason I went back because when I finished school in San Francisco, if everything was fine, I would’ve gone to CAL and applied right away. But couldn’t afford it.

So anyway, we ended up in Tule Lake. And to have someone say, ‘Aren’t you embarrassed to have been in Tule Lake,’ it’s strange. I don’t know why we can’t remember their name or who they were. And the fellow didn’t ask me, ‘Where you in Tule Lake?’ He didn’t ask me, he just came up to me and said, ‘Aren’t you embarrassed?’. Wait ’til I catch a hold of him and give him a bump on the head.

And was he older? Was he around your age?

I have no idea age-wise, I know he was a Japanese American. But you know, it’s so strange. Maybe he’s one of those that disappears.

You probably were just in shock from getting that kind of question.

My friends know where I was. But we were stuck in Tule Lake. And when the no-no boys came we were really stuck there. The thing is, they might have created a lot of dissension but they didn’t bother us. It was a huge, huge city. And we wouldn’t go this way, or that way daily, unless we had to go see somebody. We had a bunch of friends around our way which was about two wards down. And talk about wards. Each block had a kitchen, men’s bathroom, women’s bathroom, one recreation hall. The rest were barracks. And each ward consisted of nine blocks. Then they’d have this huge firebreak between these wards, in case of a fire so one wouldn’t transfer to the other. So it was a lot of walking because all we did was walk. And of course, nobody had cars. I was in Block 45.

When I first got into camp I said to my mother, ‘I want to go to Chicago or New York.’ That’s where the fashion industry was. Of course I didn’t have a penny with me. And my mother would have to give me the money. And she just put her foot down and she says, ‘Absolutely not.’ And I could tell that was her final, so it was no use prodding to say let me go. So that’s why I was stuck in Tule Lake.

Because you could have gone if you were able to get a job?

If I had the right credentials. I couldn’t even apply because I couldn’t even go out. I had a mother who didn’t like me for one reason. And she was not going to do anything to help me. I had to help her. It was a hard situation. You know, you don’t want to create dissension because you don’t know how long you’re going to be in that camp. I know most of my friends stayed put. And most of them didn’t go to a school out of their hometown. I was shocked when my mother let me go to San Francisco, you know that big city with all the crime and everything. But I’m glad we went. I got a suitcase, a regular suitcase. Found out later on that it was a cardboard suitcase. But it held up, with all my back and forth, Took me to camp and everything.

Did you and your mother always have a strained relationship since you were young?

I had to start working on the farm at five years of age. For some reason she didn’t like me. She ordered me around. But I was a good daughter, and I worked hard. It was a farm, so we went to school, came home, had to change clothes into pants, and had to get out into the field and work until it was dark. And it wasn’t only me, I talked to other friends who lived on a farm and this one girl just told me they had fruit and squash. So they had to get up in the wee hours of the morning and go pick squash. And you know, it’d be dewy, they’d be soaking wet, then had to quickly change and go to school. So there were people who had it worse than I did. I didn’t have to get up early in the morning.

Saturdays, I had to work. Sundays, I had to work. My friends were playing, and this is why I never wore pants. I have a thing about pants. I enjoy wearing dresses and skirts and things. Everybody has their reasons for doing things.

Now, when I think about it, I’m mad at Japan for creating this problem. Because the yes-yes, no-no question came up because of the war. It would never have come up before if things were okay. And I’m angry at them because they knew that they had family and relatives living in the United States and to create something like this, it’s just been really hard. And the more we talk about things, different things come up. And I do get annoyed.

Do you have some of that same anger or resentment towards what the U.S. government did?

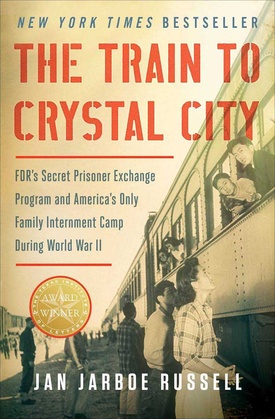

Oh, definitely. I read the book The Train to Crystal City. And in it, some woman was interviewing those radicals who hated us so much and asking different questions in the back of the book. There was Earl Warren. He hated us. At one time he lived in Alameda. He hated us so much that, I never talked to him, I never knew him but I feel like I did talk to him. The hate there was just something that I don’t think you folks could realize how awful. Franklin D. Roosevelt hated us. That’s why he signed that 9066 order.

I don’t like to hate people, we’re all humans. But this hate and prejudice was so hard to take.

What was the most shocking detail you learned from the book?

The shocking thing was Franklin D. Roosevelt had a reason for picking these people up. He probably realized they were going to have to do enemy exchange with Japan and Germany. And so they built that Crystal City so that if my dad were around and I was in Tule Lake, then they’d pick us up from Tule Lake and take us to Crystal City. Then the father or husband would come and join the family from wherever they were. It was an exchange thing, which opened my eyes.

The hard part though–so they’re bringing 500 politicians back from Japan, so they had to exchange with 500 Japanese from here. I think the parents didn’t mind, the way they treat us we might as well go, it’s a free ride [back to Japan]. It was the Niseis that didn’t want to go. And you know Japan was at war, they had nothing to eat. And I don’t think the people here realized how serious the food problem was. They were eating yam, morning, noon and night. Just thinking about it makes me sick. I love yam but not to eat, even twice a day.

Did you notice the arguing and fighting between people in camp?

That’s another thing. Partway through the war they shipped people from different camps who were loyal to Japan and so it gave Tule Lake a bad name. But I was telling someone that the camp was so huge, it wasn’t like my neighbor next door was fighting a side. And we were in a section where we were just quiet people. we used to see the young fellows with the hachimaki, they’d go running up and down the main roads, ‘Wasshoi, wasshoi.’ But they never bothered us. I thought Tule Lake was just a handful of that certain group. They never did anything in our area. We never bothered them.

In fact, they had their 5am exercise in the fire break in front of our barrack, in loud voices. So I got up at 5:00 too and exercise with them. My family’s sound asleep. So when we’d finish, I’d go and get a bucket of water and mop the floor for the day. I just couldn’t stay sleeping. I never heard of anyone getting sick with the flu or cold. None of us ever got sick. It was amazing, when I think about it.

Was it sometimes a fun time for you?

If you put it that way, I don’t know if you’d say it was a fun time. Sometimes we did farming, we’d go up to the mountain and sketch. They fed us, I mean we had a place to sleep. And one whole block used the women’s bathroom, those were not satisfactory. There are three in a row, three facing each other. I remember each time I went to take a shower, there was a little girl, she’d go with her mother and she’d just stand and she’d stare because we’re facing each other, there’s no door. And she would just stare at me. And I’d just say ‘Turn around, turn around,’ and she’d just stare all the more. [laughs].

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on December 13, 2016.

© 2016 Emiko Tsuchida