Around this time 75 years ago, Japanese and Japanese-Americans living on the Pacific coast of the United States were forcibly evacuated and sent to internment camps set up in 10 locations across the United States following the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States at the end of the previous year.

President Trump's recent executive order, which is intended to restrict entry to certain countries with large Muslim populations, is reminiscent of the Japanese American internment policy 75 years ago, which has since been deemed a shameful historical event, and has sparked backlash from the Japanese American community.

The experiences of Japanese Americans from before the war to after the war have been taken up as literary themes by many Japanese Americans. In particular, works related to the internment camps have been called "internment camp literature."

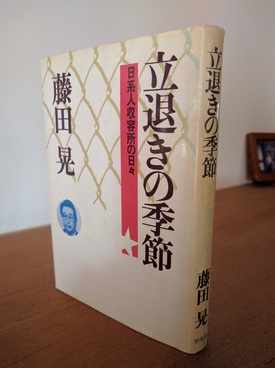

Most of these novels are written in English by second- or third-generation immigrants. However, Akira Fujita, author of "Tsuchiki no kisetsu" (1984, Heibonsha), writes in Japanese based on his own experiences. Fujita, a second-generation immigrant, is a so-called kibei who was educated in Japan, and after the war he continued to write in a literary circle called "Nanka Bungei" in Los Angeles.

By the time of the second and third generation, there were almost no people who could understand Japanese, and it was only natural that creative writing depicting Japanese American society in Japanese could only be done by a limited number of people, and was destined to eventually disappear.

Even if the facts of the experience are the same, a Japanese reader can see a clear difference between a work written in English that has been translated into Japanese and a work written in Japanese from the beginning. Also, there were first-generation and second-generation Japanese immigrants in the internment camps, and it is easy to imagine that the first-generation Japanese immigrants, who were Japanese, and the second-generation Japanese immigrants, who were born in America, would have had different perspectives on things. Expressing this in Japanese or English would make an even bigger difference. From that point of view, "Eviction Season" is interesting as a record in Japanese by someone who experienced it.

The protagonist, Isamu, is a second-generation Kibei who farmed with his father, an Issei, in California. When the war began, his father was arrested and sent to an internment camp, as he was thought to be pro-Japanese. He sold the farmland and Isamu was soon sent to the Poston internment camp in Arizona.

In the afterword, the author writes, "I have written a semi-documentary portrayal of the confusion on the Japanese farms before the eviction and the situation on the day of the eviction, and have also looked at the various conflicts between the Japanese in the camps, as well as the easy lifestyle that became a part of everyday life in the camps."

What is most striking is the rift and conflict between the Japanese and Japanese-Americans interned, and the helplessness of Isamu, who is caught up in it. Pro-Japanese Kibei Nisei and others put up a sign saying "Issei Information Bureau" and translate the notices and newspaper articles of the camp administration and distribute them to everyone. They criticize the Nisei for being pro-American, calling them "dogs," and the leader of the group is assaulted. Isamu, who helped him, is also suspected of being a "dog."

Although they are American citizens, the young Kibei have an attachment to Japan, and when the war breaks out and they are put in internment camps, they feel even more resentful towards America, and harbor hostility towards their fellow second-generation Japanese who seem to be trying to adapt to life in America. While Isamu detests their twisted feelings, he also sympathizes with Kibei, thinking that if there had been no war, he would probably have joined the American military, knowing that it was inevitable.

The country where he grew up, Japan, became a totalitarian state, and Isamu was supposed to return to America, a country of freedom and democracy, as Kibei. However, he was put in a concentration camp despite being an American citizen, and he too felt betrayed.

Isamu's thoughts, which may also be the author's own feelings, are expressed as follows.

"Having caught a glimpse of the limitless human desires and contradictions of reality caught between humanitarianism and idealism, he vomited again, emptied his stomach, was attacked by intense dizziness, and lost his footing."

"He completely lost the presence of his country, on which he could rely. When he realized the shadow of hypocrisy hidden behind the acts performed in the name of patriotism, he denied himself, on which he could rely, along with his country."

What on earth is justice? Isamu asks. He thinks about two important questions about loyalty that were asked of those who were detained in order to recruit volunteers.

"Even though Japanese citizens and Japanese people lost the assets they had built up and entered the camps thinking about the future of their descendants, they still doubt their loyalty and force the first generation and women to register as loyalists."

In the end, Isamu had no choice but to answer "No, No." In other words, he had no choice but to become a "No-No Boy." Isamu's feelings seem to overlap with the suffering of Ichiro, the protagonist of John Okada's "No-No Boy."

The human heart is weak, and the dark side of hostility, discrimination, and prejudice toward others grows in the abnormal situation of war. The anger toward the tyrannical power of the state that exposes this weakness, and war as its misguided exercise, is also felt in the work of John Okada.

* * * * *

Akira Fujita was born in California in 1920 (Taisho 9). In 1922, he was sent to be raised by his grandparents in Shimizu City (then Shizuoka Prefecture). After dropping out of Waseda University, he returned to the US. After the war began, he was transferred from the Poston internment camp to the Tule Lake internment camp, where he wrote for the literary magazine Tekkaku. He was eventually sent to the Crystal City internment camp. After the war, he regained his US citizenship in 1957, and became a member of the Southern California Literature magazine in 1965. His works include Scenes from the Farmland (Renga Shobo Shinsha).

(Titles omitted)

© 2017 Ryusuke Kawai