How did you and your wife meet?

It’s a long story. Do you want to hear it?

I do, I’m sure it’ll be a good story.

This is in June of 1941, before Pearl Harbor, I get to Los Angeles and I’m staying with the Fujisaka family. So in those days, there were a lot of Boy’s clubs and Girl’s clubs and George Fujisaka [a friend] was a member of the Shamrocks. And my wife to be Mary, was a member of the girls’ co-eds.

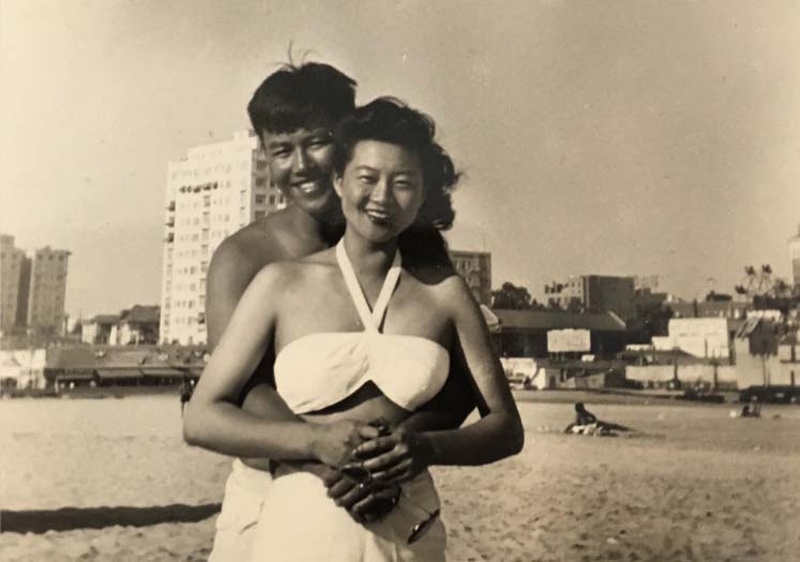

So when I showed up in L.A., Mary’s friend called her up and said, “Mary, you have to go Saturday night to the skating party we’re having with the Shamrocks.” She says, “I don’t want to go skating.” But her friend told her that all the other girls were busy, so that she had to go. So Mary says, “Okay I’ll go.” So at the Shrine roller skating rink near the USC campus, “Mary Yamamoto, this is George Shimizu.” And you know, here’s my wife-to-be: pink blouse, dirndl skirt, brown and white saddle shoes. Perfect. Love at first sight.

Wow, you remember every detail.

How could I forget? June 28th, 1941. Around 6 o’clock. We went together the rest of the summer. And then in September I had to go back to school. And we corresponded, wrote letters to each other frequently. So I was in the college infirmary and boom, Pearl Harbor. And Mary writes in her letters, “The rumor is we’re going to be kicked out of California.” And I wrote back saying, “There’s no way they can kick you out. They can’t do that. You were born in America, there’s due process. There’s nothing they can do to you to kick you out of California.”

But then, Executive Order 9066. She went to Pomona fairgrounds with her family, three months later they wind up in Heart Mountain. And I never got to Heart Mountain. Mary and I were scheduled to go in December and then the army said no, you can’t go because you’re shipping out in the middle of December. So we spent Christmas of ’42 and ’43 together. We left Camp Savage in early ’43. She left camp early as a house girl to come up to Minneapolis where we got married. But her older sister Amy was still in Heart Mountain and Amy later came to live in Minneapolis because they knew the mother and father were safe in Heart Mountain. I think the Issei women enjoyed camp life, from what I heard. Because a lot of the farmer’s wives were feeding the family and all the farm help. Tough job. So when they went to camp, food was prepared for them.

Did Mary stay in camp the entire time?

She had gone from Heart Mountain to Denver, Colorado as a house girl. She was there for three days and told the lady of the house, “I can’t do this work. I’ve never done housework.” So she left and she went to the WRA office and told the lady there, I quit my job as a house girl. She says, “Mary you have to go back. You’re ruining it for all the other Nisei girls.” So the lady asked her what she could do. Mary said that she could sew. So she went to work making jackets for the U.S. Army. And she was so good that the owner of the manufacturing company said if you have any more people like Mary, we’ll take them all. Then she worked in Minneapolis for two and a half years with a wonderful Norwegian family that took her in.

Then on April 2nd, 1943, Mary and I got married. On every Friday night we got weekend leave, and then on Monday morning, we went back to Camp Savage. I think Mary and I were one of the first Nisei couples to get married at Camp Savage. They told me I couldn’t eat in the mess hall with the other guys because I was on rations when we got married. So I had to eat with the Japanese instructors. The crazy thing is I knew a lot of them from Tokyo days.

Let me tell you a story about my wife. It must’ve been about in January or February of ’45. My wife and her sister Amy and a friend of theirs were going to Heart Mountain, which was 500 miles away and on the train going from Minneapolis to Wyoming, this American fellow–redneck–kept teasing my wife. And my wife Mary never said a word. And this redneck was teasing her until her sister Amy spoke up and said, “Hey, knock it off! Her husband’s a Sergeant in the U.S Army fighting in the Philippines and here you are, riding a train in Wyoming. You should be ashamed of yourself.” And the guy looked at Amy and looked at my wife, and he sort of sheepishly walked away. And you know, that train full of passengers said, “Good for you, good for you!” Good for Amy.

Absolutely. When you came back to California, how did you and Mary meet again?

They had all come back from Minneapolis to Los Angeles. And when I got discharged, they were at the All People’s Church near San Pedro. I had their address because I got a lot of letters from her while I was in the hospital. But I had no phone number. So I found out that a bus went right down San Pedro street and I got off, and I rang the doorbell at 7 o’clock in the morning. And a fellow answers and I said, “I’m George Shimizu.” And he says, “I’ll get Mary.” And Mary came down and you know, we both broke down and cried.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on August 1, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida