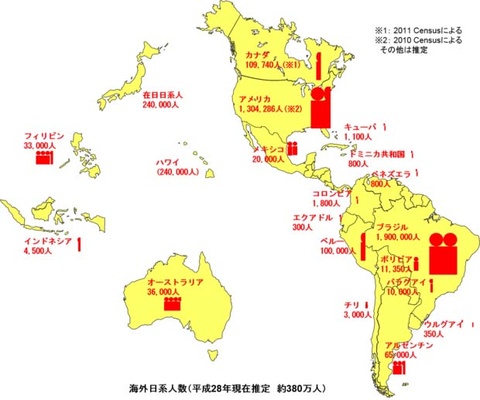

Currently, there are approximately 3.5 million people of Japanese descent living overseas.1 Although it depends on how you define "Japanese descent," here we define it as Japanese people living overseas and their descendants. Some third- and fourth-generation Japanese do not consider themselves to be of Japanese descent, but these people are included in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' statistics on the number of Japanese people residing overseas, totaling 1.33 million (870,000 long-term residents and 460,000 permanent residents) .2

Before the Meiji Restoration, Japan had a strong image of isolation. However, even during the period of isolation, information and goods flowed into the country, albeit to a limited extent, through Dejima in Nagasaki, and it is said that in the early 17th century, many Christians fled aboard foreign ships to Macau, which was under Portuguese rule, and Manila and Mindanao in the Philippines, which were under Spanish rule at the time, to escape persecution of Christians. Furthermore, before the isolation, there was overseas exchange through trade with the Ryukyu Islands, Korea, and Qing Dynasty, and there was also contact with foreign countries through wars, such as the Mongol invasion in the 13th century3 and Toyotomi Hideyoshi's invasion of Korea at the end of the 16th century4.

However, it was Perry's arrival in 1853 that forced Japan to fully open its ports. The first Japanese to go overseas were 153 people known as the "Gannenmono" who traveled to Hawaii in 1868, the first year of the Meiji era. This project was the result of an agreement between the shogunate and the Kingdom of Hawaii, and due to the confusion of the Meiji government, they were sent to Hawaii as private contract laborers without being issued passports. After that, from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, many Japanese emigrated to the United States, Peru, Bolivia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and other countries, and there were Japanese who had either relocated from other countries or emigrated individually to Cuba, Colombia, Venezuela, Uruguay, and Chile. During the war, overseas migration was temporarily suspended, but resumed after the war, with many Japanese emigrated to Central and South America.

It is said that Japanese people in Latin America generally have a strong sense of identity as "Japanese." In particular, there are large colonias (places of settlement) in countries such as Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia, where people live together and form communities and still have strong feelings for Japan. The word " colonia5 " literally means "colony," but in South America, both in Spanish and Portuguese, it does not carry much of a negative colonial connotation and generally refers to Japanese settlements. Some settlements even have large signs reading "Colonia Japonesa (Japanese settlement)" at their entrances6 .

So how many Japanese were living overseas as of 1940? According to multiple statistics, it is estimated that there were 190,000 Japanese in Brazil, 20,000 in Peru, and around 5,000 each in Argentina and Mexico, totaling about 230,000 Japanese in South America. In North America, there were 94,000 on the US mainland, 92,000 in Hawaii, and 20,000 in Canada. This means that there were 430,000 Japanese in the Americas alone. This may seem like a large number, but the total population of Japan at the time was 72 million, so North and South America combined made up only 0.6% of the total population.

Meanwhile, just before the outbreak of the war, there were seven times as many Japanese in Asia and Oceania as there were in the Americas. At the time, there were 350,000 Japanese in Taiwan, a Japanese territory, 380,000 in South Sakhalin (now Sakhalin), and 690,000 on the Korean Peninsula. There were also 890,000 Japanese in Manchukuo, which was effectively under Japanese control, 200,000 in the Kwantung Leased Territory (the Chinese city of Dalian, which was a Japanese leased territory at the time), and 80,000 in the South Sea Islands (the Mariana Islands, Caroline Islands, Marshall Islands, etc., north of the equator in the Western Pacific). And there were 280,000 Japanese living in mainland China, exceeding the number of Japanese in South America. There were approximately 2.8 million Japanese living in Asia and Oceania alone (4% of Japan's total population).

Among the immigrants to Asian countries were civil servants and company employees who worked in the administration of colonial policies, but many were also farmers who suffered from poor harvests, disasters, poverty, and unemployment. During the war, 3 million Japanese soldiers served in various parts of Asia. After the war, most of them returned to Japan as repatriates, but some stayed behind for various reasons. They were also "Japanese descendants" by definition, but some of them experienced a time when they were not even allowed to recognize or express themselves as such. However, in Indonesia and Vietnam, there were Japanese soldiers who disobeyed Japan's orders to surrender and disarmament after the war and stayed there to fight for the independence of those countries, and they and their descendants were recognized as heroes, and some even obtained citizenship and became honorary citizens. 7 Meanwhile, in the Philippines, there were cases where people went into hiding and lived on the run immediately after the end of the war, or changed their names to live as locals so as not to stand out. Some of them were retaliated against and killed by local people. Similar situations were occurring in the Korean Peninsula, China, and Manchuria, but the suffering of those who remained seems to have been too severe to describe in a single word.

Currently, orphans left behind in China8 and Japanese left behind in the Philippines and their children of Japanese descent9 can work and study in Japan without restrictions as second or third generation Japanese, just like Japanese people in South America, if their identity is proven through rigorous background checks. If they stay in Japan for a certain number of years and gain economic strength, they can obtain permanent residency. In recent years, the number of "Japanese people living in Japan" becoming "naturalized Japanese" has been gradually increasing. In particular, those who have stayed in Japan for more than 20 years seem to be going through the naturalization process for the whole family, with the children planning to go on to higher education institutions or find employment. Among people from Central and South America, Peruvians are more likely to change their nationality to Japanese than Brazilians.

Notes:

1. The Association of Japanese Abroad, a public interest foundation , estimates that the world population of Japanese descendants is 3.8 million. However, this number varies depending on which generations are included in the term "Japanese descendants." In fact, in the United States, Brazil, Peru, and other countries, many of the first generation of Japanese immigrants have already passed away, the second generation is quite old, and Japanese communities are entering the era of the third and fourth generations. In addition, there is a growing trend of intermarriage with non-Japanese, making it difficult to determine the exact number of Japanese descendants.

2. Statistics from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the number of Japanese nationals residing overseas , as of October 2016

3. There were two Mongol invasions during the Kamakura Shogunate. The first was in 1274, when the Mongol Empire and Goryeo allied forces came to Japan with 26,000 soldiers on 900 ships. While retreating, the Mongol allied forces encountered a storm and many soldiers drowned. The second was in 1281, when they sent 140,000 soldiers on 4,400 ships. This time, a storm hit just before the general attack, and most of the ships carrying 140,000 soldiers sank.

4. In 1592, Hideyoshi dispatched 160,000 troops to Korea for the first time. The second dispatch took place from 1597 to 1598, and was the second challenge.

5. According to the Kojien dictionary, "immigration" means moving to another part of the country or to a foreign land for the purpose of development or colonization, while "colonization" means encouraging the migration or settlement of one's own people in a foreign territory or undeveloped land, and promoting its development and control. Also, a "colony" is an area formed by colonization from a certain country, or an area that has been politically and economically subjugated by a certain country's economic or military invasion, and the expansion of such a policy is called "colonialism" or colonialism.

6. In South America, foreign communities are often referred to as "colectividad" (meaning group or organization).

7. There is no exact data, but it is said that 1,000 Japanese soldiers remained in Indonesia and 700 in Vietnam. They not only fought for their countries, but some of them were officers and were involved in the military system and training of their soldiers. For their achievements, they were awarded the honor of honorary citizens.

8. They are the children of Japanese immigrants who moved to the former Manchuria, but were left behind in the chaos of the end of the war and were raised by Chinese stepparents. They began coming to Japan in the 1980s, and currently over 1,500 of them are allowed to live in Japan and have settled there permanently.

9. Japanese who emigrated before the war and their children. These include those who were unable to return after the war ended, or children born to local Filipinos who were unable to be brought to Japan. In recent years, the Nippon Foundation has been providing legal support for identity checks and the restoration of family registers.

© 2017 Alberto J. Matsumoto