We have spent two-thirds of our lives in the United States and we feel we are more American than Japanese; we are willing to do anything we may be asked to do to help our foster mother.

A Portland Issei, January 23, 19421

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor had a profound impact on Issei life. Immediately classified as “enemy aliens,” they were no longer able to assure security for themselves or for their children. “Asleep or awake, I felt as if I were losing the color in my face,” said a Portland merchant. “I knew that our lives as well as our property were at stake. I wondered what would happen to us.”2 They faced a difficult choice. On the one hand, Japan was the country in which their parents, siblings, and friends lived. Moreover, denied naturalization rights in America, Japan was still their country of citizenship. On the other hand, America was their adopted country where they had established their families. It was also the country where their children and grandchildren would remain for the years to come. A Hood River farmer recalls the anguish of choosing one over the other. “We were all terror-stricken at the news. War between America, where we would live until death, and Japan, where we came from! I am a Japanese subject, but my children are Nisei, and American citizens. We Issei were sorely troubled by this war.”3

Yet, the great majority of the Issei cooperated with the war effort of the United States from the beginning. Parents encouraged their sons and daughters to render service to their country in the time of crisis. For example, on the very day of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Masuo Yasui of Hood River sent a telegram to his son, Minoru in Chicago, urging him to serve in the military.4 Many Issei also contributed financially to the country. According to Yasukichi Iwasaki, when the government lifted the freeze on the Issei bank accounts, he immediately withdrew $425, spent $375 for U.S. Defense bonds and donated $25 to the Red Cross.5

The Issei publicly showed their support to the United States. On January 23, 1942, Portland residents held a mass meeting and sent President Roosevelt a telegram to affirm their loyalty: “We old Japanese pledge our services and our resources to destroy Japan and her Axis partners who challenge our democracy.”6 In Hood River, all the Issei signed a common pledge which read:

Most of the alien Japanese residents are devoted to this great Democratic America although we are not eligible for citizenship. We love this country so much that we wish to live here permanently…. May we pledge our loyalty to the Stars and Stripes just as do our children who are patriotic American citizens.7

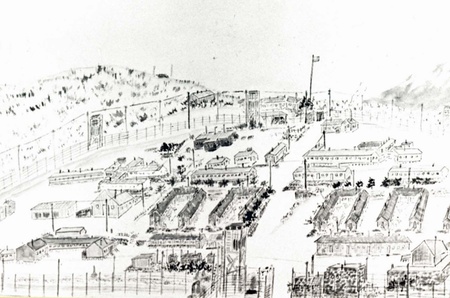

Portland, Oregon, 1941 (Courtesy of L. Sato, Japanese American National Museum [92.182. 3])

Still the Issei were bewildered, confused, angry, frightened, and helpless. The continuous fear of the unknown future, coupled with an upsurge of anti-Japanese sentiments, brought about an enormous emotional drain. Yasukichi Iwasaki repeatedly expressed such feelings in his diary. On December 13, he wrote, “The war is causing all sorts of worries among the Issei, and nobody can work. We all seem absent-minded.”8 Two weeks later, he made a similar entry: “Ever since the war broke out, I’ve been feeling unpleasant. Being in the state of emptiness, I do not do anything, I do not have anything to write about.”9 At one point, the mounting sense of fear and helplessness caused Iwasaki to stop writing in his diary for two weeks, because he “lost courage to do so.”10

The war suddenly stripped the Issei of autonomy over their life and community. On December 7, President Roosevelt issued an executive proclamation, under which their activities were greatly restricted. The local law enforcement authorities and the FBI destroyed the leadership of the Japanese community by rounding up Issei leaders and sending them to various Justice Department prison camps. This resulted in the dissolution of the Japanese associations and other organizations that had served to combat social and legal discrimination prior to 1941.

Under these circumstances, the Nisei began to assume new leadership in the community. Between December, 1941 and March, 1942, federal and local governments as well as military authorities issued a number of orders and proclamations. Given their limited English skills and their “enemy alien” status, the Issei turned to their children and to the JACL to interpret the orders and meet the requirements.11 For instance, on behalf of his parents, a Nisei man wrote to the JACL to inquire about travel restrictions on the Issei. According to the letter, his family had farms in Boring and Sherwood. Both farms needed attention as winter passed into spring. In reply, the JACL secretary sent him applications for travel permits with procedural instructions.12 On another occasion, when the city of Portland denied the renewal of business licenses to Japanese immigrant merchants, the JACL acted as their agent and asked the governor to intervene, although it was in vain.13 As the Issei saw it, the JACL was the only viable organization to represent the interests of the Japanese community.

Meanwhile, the pressure of mass “evacuation” became greater day by day. In the middle of February, various American Legion posts started to demand the removal of both the Issei and the Nisei from Oregon.14 At the Congressional committee hearing held in Portland, the Mayor of Portland and the delegates from Hood River warned that the presence of Japanese residents was a threat to national security. Anticipating the economic benefits of Japanese exclusion, the Hood River Apple Growers’ Association openly stated that the white farmers were prepared and desirous of taking “over the [Japanese] properties and running them efficiently.”15

The federal government was moving toward the mass exclusion of Japanese residents from the Pacific Coast states. On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the army to remove any individual from designated zones without due process of law. Less than two weeks later, John L. DeWitt, Commander of the Western Defense Command, issued Pacific Proclamation No. 1, which designated the western half of California, Washington, and Oregon as Military Area No. 1 and the rest of these states as Military Area No. 2. This proclamation also suggested that the Japanese might be excluded from Military Area No. 1.

The diary of Yasukichi Iwasaki illustrates the confusion that the people went through after DeWitt’s order.16 For the first time on March 8, Iwasaki discussed the likelihood of “evacuation” with his sons. By the following day, they agreed to lease their property during the period of evacuation and informed their lawyer of that decision. His son was to negotiate with the lawyer and a prospective lessor and to liquidate the family assets, while Iwasaki himself concentrated on the management of their 50-acre farm. However, as Iwasaki made his son prepare for evacuation, he also asked for loans from a local bank and cannery for the harvest of strawberries in the summer. This contradictory behavior reflected his mixed emotions. On the one hand, he had to accept the reality of evacuation, “no matter how unwilling he was.”17 On the other hand, he still could not believe that he would actually leave Hillsboro before the harvest.

Nonetheless, the answers that the bank and the cannery gave to Iwasaki forced him to realize the reality. The former refused any loan to the Japanese, whether there was collateral or not. The latter abruptly canceled the verbal agreement which it had with Iwasaki for years. After these rejections, his diary was filled with expressions of futility and depression. On March 18, he wrote, "The “thought of evacuation has just tormented me since morning. I cannot go about my work at all.”18 Four days later, he suggested that he had lost a sense of purpose in life. “I feel very dispirited. I just live to eat everyday. I will never forget this wasteful life.”19 In another entry, Iwasaki stated that the circumstances drove “us Japanese almost to distraction.”20 A few days later, Iwasaki concluded a lease contract with a white farmer. Many Issei, like Iwasaki, experienced indignation and dejection, since they too, found their customers, associates and neighbors turning their backs on them.21

The forced evacuation of the Oregon Japanese and the American-born Nisei and Sansei took place in May, 1942. The Portland residents were the first to be uprooted from their community to an “assembly center,” followed by those from Gresham as well as Washington, Clackamas, Columbia, and Clatsop Counties.22 Four months later, 2,318 Oregon Japanese and Nisei were transported by train to the Minidoka “Relocation Center” in Idaho, while a few hundred were sent to the centers in Tule Lake, California, and in Heart Mountain, Wyoming.23 The Japanese of Hood River and Marion Counties were not part of this group. They were taken to the assembly center in Pinedale, California, and then to Tule Lake.24 When mass removal was completed, the Minidoka internment camp had 65.3 percent of the Oregon Issei and Nisei, Tule Lake 32.2 percent, and Heart Mountain the rest.25

Notes:

1. The Oregonian, January 24, 1942.

2. Eileen Sunada Sarasohn, The Issei: Portrait, An Oral History (Palo Alto, California: Pacific Books, Publishers, 1990), p. 175.

3. Kazuo Ito, Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America, p. 691.

4. Telegram from Masuo Yasui to Minoru Yasui, December 7, 1941, in Homer Yasui Collection. On March 28, 1942, Minoru Yasui challenged the constitutionality of the curfew order to Japanese Americans issued by the military by deliberately having himself arrested. In June, 1943, the United States Supreme Court ruled for the conviction of Minoru and hence the legality of the curfew order. Later in 1983, he filed a petition to reopen his case to overturn the previous decision, but his death in 1986 terminated the appeal process.

5. Yasukichi Iwasaki Diary, December 18, 1941, in Japanese American Research Project Collection (hereafter JARP), UCLA.

6. The Oregonian, January 24, 1942.

7. Marvin G. Pursinger, “Oregon’s Japanese in World War II, A History of Compulsory Relocation,” pp. 81-82.

8. Yasukichi Iwasaki Diary, December 13, 1941, in JARP Collection, UCLA.

9. Ibid., December 27, 1941.

10. Ibid., March 9, 1942.

11. The government and military orders included travel restriction, enemy alien registration, and the confiscation of short-wave radios, cameras, and firearms.

12. Letter from K. Nishikawa to JACL Portland chapter, February 10, 1942, and a reply from Executive secretary to K. Nishikawa, February 16, 1942 in the Portland JACL Collection.

13. Marvin G. Pursinger, “Oregon’s Japanese in World War II, A History of Compulsory Relocation,” pp. 87-90.

14. Ibid., PP. 107-114.

15. Ibid., pp. 104-106.

16. See Yasukichi Iwasaki Diary, March 9-18, 1942, in the JARP Collection, UCLA.

17. Ibid., March 12, 1942.

18. Ibid., March 18, 1942.

19. Ibid., March 22, 1942.

20. Ibid., March 30, 1942.

21. Also see Eileen Sunada Saeasohn, The Issei: Portrait of a Pioneer, An Oral History, pp. 167-168.

22. Janet Cormack, Ed., “Portland Assembly Center: Diary of Saku Tomita,” Zaigaku Kodachi and Jan Heikkala, trans., Oregon Historical Quarterly 81:2 (1980), 169; and Yasukichi Iwasaki Diary, May 14, 1942, in JARP Collection, UCLA.

23. Evacuazette 2.2, August 19, 1942; also see Janet Cormack, Ed., “Portland Assembly Center: Diary of Saku Tomita,” p. 171.

24. War Relocation Authority (WRA), The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1946), pp. 64-65.

25. Ibid., pp. 64-65.

* This article was originally published in In This Great Land of Freedom: The Japanese Pioneers of Oregon (1993).

© 1993 Japanese American National Museum