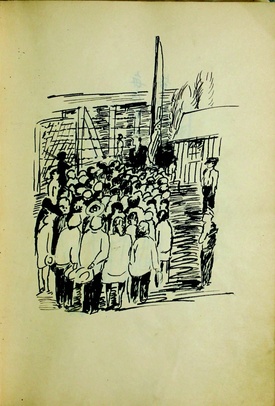

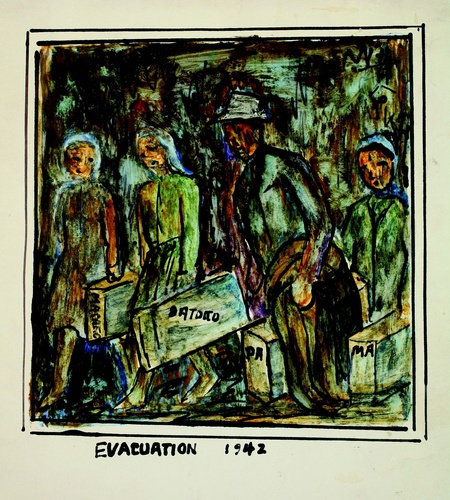

The women were standing just about eye level with me, their faces sketched on the wall by Issei artist Takuichi Fujii. They were standing in front of barracks at Minidoka, but in the picture they seemed—and felt— at an arm’s length away. One woman had her hand up to her face, as if wiping away tears. The other woman had her hand covering her mouth, the kind of involuntary gesture you make when your breath is taken away, when you want to stop yourself from crying.

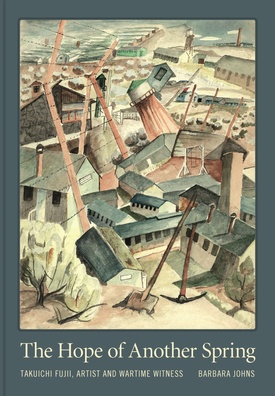

These are the women I was facing as I walked into the Witness to Wartime exhibit at the Washington State History Museum in September. I had already read and reviewed the book which complements the exhibit, The Hope of Another Spring—it’s a splendid work of art history by Barbara Johns. I had already read excerpts from MINIDOKA XX, the sketchbook diary that Fujii kept and is now the most complete Issei account of incarceration that we have available, according to historian Roger Daniels. Fujii was incarcerated in Puyallup and then Minidoka during World War II. In that book I had already read art historian Sandy Kita’s thoughtful and moving analysis of his grandfather’s diary, both from a grandson’s perspective, a co-translator’s perspective, and a Japanese art history perspective. Excerpts from Fujii’s diary were mounted on the walls around me at the exhibit, and a digital version of the diary was available for me to scroll through at my leisure. The vibrant blue portfolio which once contained these paintings, which Fujii had illustrated with a painting of Seattle on fire and marked “1942-1945,” was also inside a Plexiglass case for me to see in the next room.

But this was later. When the rest of the press tour had moved on, I stood transfixed for a minute in front of these two grieving women. We made an odd triangle of sorts: two of us on the wall, sketched in black ink on white paper, one of us standing in living color. And yet two of us had our hands up to our mouths, one living and one dead.

Such is the power of the Takuichi Fujii exhibit at the History Museum. It’s an exhibit you might expect at an art museum, and I hope it will go on to other art museums and history museums around the country. But Johns (and in this case, her collaborator Mary Mikel Stump at the Washington State History Museum) has curated an exhibit which frames Fujii as artist, as witness, as community historian, and the combination is powerful.

An artist and businessman who lived in Seattle, Fujii’s work had reached exhibition status and prominence before the war. He was forcibly removed from Seattle with his family to “Camp Harmony” in Puyallup, and then to Minidoka. After the war he lived briefly in Ogden Utah, and then to Chicago, where he lived for the rest of his life. He never returned to Seattle. He left no personal papers, no correspondence, half a dozen photos. But his work remained for decades, hidden from public view—first in one of his daughters’ houses, then later in his grandson Sandy Kita’s house. In 2017, Witness to Wartime represents the first time that the majority of these works have been available for the public to view.

To stand in the space of the History Museum—itself, another frame for the exhibit— felt important. Located in Tacoma, the Museum itself is just thirty-five miles from Seattle, where Fujii and his family had built a life in Seattle’s Nihonmachi. It is less than ten miles from the fairgrounds at Puyallup where Fujii and his family were first incarcerated, and where the very first Japanese American Day of Remembrance was held in 1976. Sandy Kita’s wife Terry had searched for decades to find out more about her husband’s grandfather, and an online introduction through Seattle’s Wing Luke Asian Museum brought the Kitas to meet Barbara Johns.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Johns knew that the collection “had to be an exhibition,” she says in a phone interview. As an art historian of modernism, she recognized the artistic value of Fujii’s work—and many of the watercolors and sketches demonstrate modernist experimentation with perspective, shapes, lines. But she persisted through a rigorous process with the reviewers at the University of Washington Press for the book, as well as even more training in Japanese American studies past her dissertation on three Issei painters. She now credits “a village” which brought the exhibit to life.

The History Museum’s Director of Audience Engagement, Mary Mikel Stump, is one such collaborator. The two worked together in order to choose the right gallery spaces, and with Stump’s own background in art exhibitions, the spaces are a quiet justice to Fujii’s work. “The day of the exhibition opening,” says Stump in a recent email interview, “there were multiple people in attendance who either had been at Minidoka or who had relatives and/or loved ones there. To see and hear from them how meaningful it was to be able to see what their experiences were like was life-altering for me.”

Barbara Johns was gratified to take the Kitas to the History Museum in September, to see Sandy Kita stand next to his grandfather’s self-portrait, to hear him speak and show audience members a special cardboard box. “Everything in the show was originally in a cardboard box,” Sandy Kita wrote to me in an email after he had seen the show. “I always took [the box] with me when I moved, but would not open [it]. My wife Terry was incensed at how my Grandfather and his art had been dismissed and kept bugging me about not letting him or his art go to waste. So I opened the box. I was a trained art historian by then and the professional part of me quite objectively said this was very good work. When I saw the exhibit, I couldn't have been happier, but what moved me the most was how Terry responded to it. She cried.”

There are many such boxes holding Japanese American history—both physical and psychological—as we’ve discovered over decades. But they continue to speak. Face to face with those two Issei women in Fujii’s painting at the History Museum, I was still moved. Over a month from that visit, I couldn’t forget those women who have felt so lost to me in my study of Japanese American literature and history due to time, distance, and language barriers. The Issei women who were so openly, nakedly grieving in Fujii’s painting, speaking as I’ve never been spoken to before.

I am still thinking of my Issei grandmother Shizuko, who died when I was only 2 years old. There are a few pictures I have of her: her passport, sepia family portraits where she and my grandfather are dour-faced, exhausted, barely acknowledging the camera, even surrounded by all six of their children. But there are other pictures of us together, with me on her lap. I still have two quilts that she made, the ones she had on her lap when she was holding me; those quilts are on my living room couch now. My grandmother is smiling in many of those pictures of us together. I have to remember that.

* * * * *

Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diaries of Takuichi Fujii is at the Washington State History Museum (1911 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma) through January 1, 2018, The museum is open Tuesday - Sunday 10 AM - 5 PM.

The Hope of Another Spring, by Barbara Johns, is available from the University of Washington Press.

© 2017 Tamiko Nimura