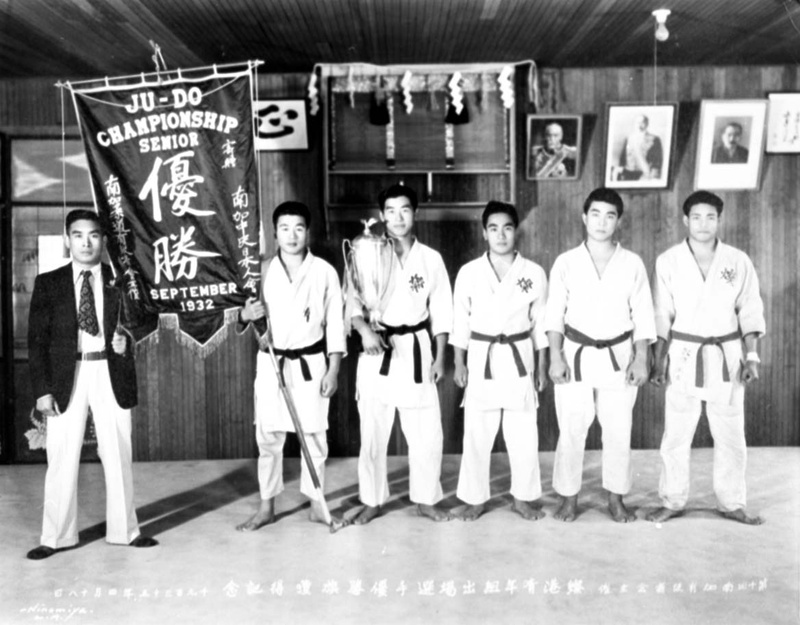

Judo has been an important cultural activity in the Japanese American community since its early days. In the 1930s, despite the Great Depression, there were Japanese American groups all over the country that worked to promote international friendship through judo. In Southern California, the Southern California Kodokan Judo Dan Association took the lead in sending a group of Nisei who had achieved outstanding results to Japan as a judo observation team. One of the Nisei chosen as the representative was Clarence Iwao Nishizu, who worked in real estate in Orange County and was known for his research into the history of the local Japanese American community.

According to Nishizu, the total travel expenses for each member of the judo tour group was $275, which is roughly 400,000 yen in today's value. This was a huge burden for an average family at the time. Even the Nishizu family found it difficult to come up with such a large sum of money, so Nishizu asked an Issei acquaintance, Mr. Murata, for help in finding him a job harvesting crops and raised the travel expenses himself. 1

In mid-September 1931, the Nisei youths selected as a judo observer group boarded the Nippon Yusen Kaisha ship Taiyo Maru at San Pedro Harbor and headed for Yokohama. On the way, they stopped in Honolulu and participated in a judo tournament held there. About a week later, they arrived at Yokohama Harbor and boarded a train from Sakuragicho Station to the YMCA Hotel in Kanda. This was their accommodation in Tokyo.

They stayed in Tokyo for about a week, and in addition to training at the Kodokan, they visited Nikko and Sengakuji Temple, and had the opportunity to meet many prominent figures in Japanese society at the time, including judoka Kyuzo Mifune, known as the "god of judo," Ichiro Hatoyama (former prime minister and first president of the Liberal Democratic Party), Seiji Noma (founder of Kodansha), Sadao Araki (general and Class A war criminal), Takejiro Tokonami (former Minister of the Interior), Tatsuo Yamamoto (former governor of the Bank of Japan), Isamu Takeshita (navy admiral), and Shohei Fujinuma (former superintendent general of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department). According to Nishizu, the meetings with such prominent figures were made possible because some of the people who organized the itinerary for the judo tour were on friendly terms with prominent figures in Japanese society at the time.

One extremely valuable experience for them was meeting Admiral Togo Heihachiro. They were surprised at how humble Togo was, despite the fact that he was a famous commander who led Japan to victory in the Russo-Japanese War and left his mark on modern Japanese history.

According to Nishizu, Togo's words were thoughtful and carried weight, and he spoke these words to the young second-generation Japanese.

You were born and raised in America.

You are Americans.If America were to go to war with any country,

You have to fight as Americans.And you are Americans,

Don't forget about your Japanese ancestors.(emphasis by author)

After finishing their schedule in Tokyo, they boarded a train from Tokyo Station the next morning and visited various parts of Japan, including Nagoya, Kyoto, Nara, Hiroshima, Kumamoto, and Kagoshima. They then participated in joint training sessions and friendly matches at local dojos, schools, and police stations.

During this time, Nishizu-san was able to visit his father's hometown of Fukuoka and his siblings and other relatives. This was his first visit to his relatives, and it was a very emotional memory for him. The Nishizu family in Fukuoka also warmly welcomed Nishizu-san, a visitor from California.

After completing their training in various parts of Japan, the Nisei left Kagoshima by boat and headed straight for the overseas territories2 . First, they visited Busan and Gyeongseong (Seoul), where they participated in joint training and friendly matches with Japanese and Korean people at local police stations. After that, they traveled by train to mainland China, visiting Mukden, Harbin, and Dalian. There, too, they participated in joint training and friendly matches with Japanese people living there.

After completing their visit to mainland China, they returned to the mainland by ship, and a few days later left the port of Yokohama and returned to Southern California. Their stay in Japan as a judo observation team lasted about two months. Visiting not only the Japanese archipelago but also overseas territories was an extremely valuable experience, not only for the study of judo, but also for understanding the state of affairs in Japan at the time.

Nisei's cross-cultural experience

For the young second-generation Japanese who visited Japan, Japanese society was a foreign cultural space, but also a space in which they felt uniquely comfortable. Many had attended local Japanese language schools and had some knowledge of Japanese culture and customs, but for most, it was their first visit to Japan. Nishizu later told her daughter Jane about her experience at the time, saying, "I felt like I was part of the majority."

The first thing that surprised them about Japan was the high level of hospitality. They were particularly impressed by the excellent service they received when they stayed at famous inns during their visit. When it was mealtime, the landlady and maid carefully brought multi-tiered trays of food to their rooms. Then, toward evening, the landlady and maid came back to their rooms again and neatly laid out their futons. It was the first time in their lives that they had been treated like this.

On the other hand, the difference in lifestyle was a source of surprise for the young second generation Japanese who were born and raised in America. Having experienced life without chairs, they enjoyed the delicious food, but because they had to sit on cushions throughout the meal, their legs became numb by the time they finished eating and they could no longer walk as they wished.

The biggest culture shock was the Japanese-style toilet. In America, they had never had the experience of squatting on a toilet, so using a Japanese-style toilet was "painful" for them. According to Nishizu, the fact that the toilets at the inn were unisex was another culture shock. In America, it was natural for toilets in lodgings and public facilities to be gender-segregated.

A group of young Nisei (second generation) Japanese was sent to Japan from fall to winter 1931 to observe judo. It was an important page in the history of the relationship between Japanese Americans and Japanese people in the Japanese American community before the war. At that time, I believe there was still a relationship that could be called "bonds" between the Japanese American community and Japanese society. However, with the outbreak of the Japan-US war, unfortunately, the relationship with Japanese Americans was effectively "severed." After Japan's defeat, many Japanese Americans distanced themselves from Japan and Japanese culture, but temporary "relationships" were rebuilt through the Lala supplies, the agricultural labor dispatch program (short-term farming), and the bid for the 1964 Summer Olympics. However, none of these were long-term, and there were voices in the Japanese American community that it was better for Japanese and Japanese Americans to go their separate ways.

As we enter the 21st century, new efforts are being made between Japanese Americans and Japanese people. Although it is a small-scale project, after the Great East Japan Earthquake, the Japanese branch of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) took the lead in starting a scholarship program (without repayment obligations) for students from the disaster-stricken areas attending Meiji Gakuin University. This kind of movement may be temporary, like the time before the war when judo observation groups were sent to Japan, but I would like to continue to pay attention to it with interest.

Note

1. The Nishizu family originally ran a liquor store in Rafu (Los Angeles), but after Prohibition was enacted, they moved from Rafu to Orange County and began making a living as farmers. In the early 1930s, the Great Depression caused difficulties for the family, but by the late 1930s, the family's situation had improved to the point where they were able to purchase the most advanced agricultural equipment of the time. However, the outbreak of the war brought the family to the brink of bankruptcy, and the family was sent to the Heart Mountain Internment Camp. After several twists and turns after the war, the family returned to Orange County in the 1950s, where they farmed before moving into real estate.

2. At that time, areas that came under Japanese control after the Meiji Restoration, such as Okinawa, the Korean Peninsula, and even Taiwan, were called "gaiichi" (foreign territories).

References:

Nishizu, Clarence Iwao . Interviewed with Arthur A. Hansen. Honorable Stephen K. Tamura Oral History Project. California State University, Fullerton. Interviewed on June 14, 1982. Published in 1991.

© 2017 Takamichi Go