“It was hard, it was hard on the parents. Was it hard on me? I don’t know, I don’t remember that much, the hardship. But the parents, my god. Could I do it? No. I couldn’t do it. I can’t imagine myself doing it.”

—Howard Yamamoto

Out of the 110,000 Japanese Americans who were thrown in the internment camps, 130 escaped the stark reality of mess hall food, barbed wire, and guard towers. Four-year-old Howard Yamamoto was one of them. And though he was lucky to stay out of camp, the experience of fleeing internment was not without its own hardships.

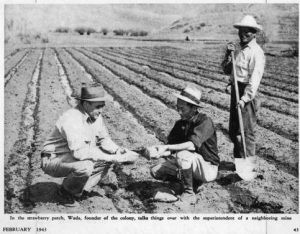

Fred Wada, a savvy businessman who worked in produce in Oakland, was adamant about leading a colony of “free” Japanese out of California. The best analogy for what he accomplished is akin to Noah’s Ark by gathering a group of people with specific talents he needed to build a community from scratch: bulk skilled farmers, carpenters, nurses, electricians, pharmacists, and plumbers. He scoured different counties and cities to resettle, finding it difficult to overcome the deeply-entrenched anti-Japanese sentiment that was rampant in even in the neighboring states. It wasn’t until he met George Fisher, a landowner in Utah with 3,000 acres (much of it rocky and unsuitable for farming) that both men saw a mutually beneficial opportunity. While Wada could start his community on the land, Fisher would have complimentary labor to make the land fertile on Keetley farms.

Initially, the surrounding community from Summit and Wasatch counties were against the move-in. The city council urged Utah’s Governor Herbert B. Maw to keep the group from coming, while the people of nearby Heber City also complained. The backlash manifested itself in violence, too: someone threw dynamite towards a shed on the property.

* * * * *

Howard recalls his story from the beginning:

I’m just trying to gather my thoughts here. Basically when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, first of all, any of the minority, they were considered second class citizens. So, I mean this is just my thought. A lot of people have criticized our generation. Why didn’t we fight it? Why didn’t we protest? Well, when you’re considered a small group and another thing, Japanese just don’t say anything.

It’s not in the culture.

No. You know why this interest is up now? It’s the Sanseis, third generation.

It’s very different, the people who went through it versus people that are relatives hearing about it.

Our generation started—because of people like you—were starting to pick up on it. It was kind of interesting, how much people knew about it. When I was taking a course at San Francisco State, it was something had to do with, social living. I gave mine on the internment. Showed old pictures of it, and she stopped me.

“What are you talking about?”

“Oh they were interned, when the war started.”

“What do you mean?”

She was from the Midwest.

No way.

No, she didn’t know. The prof., well she was a visiting prof, she really didn’t know what I was talking about. And she said, “What are these pictures here, the barracks?” I said, “They were in prison, essentially, behind barbed wires.” “No!” A couple of the students go, “Oh yeah.” So I went through it and gave them a little spiel. But you could see it in her eyes. She was puzzled.

I’m sure she couldn’t even conceive of it.

You just don’t gather a hundred thousand people and put them away. Of course it wasn’t really publicized. But anyway, it was interesting this perception, of what happened during WWII. Especially in the West Coast.

When the war started, they were given few months, I think we were given until February, March. Let me show you.

Howard goes to look through a box of his old photos and documents. He showed me an old photo from his middle school days in Berkeley, my dad was in several of his class pictures.

Well when the war started, I was four years old. Or just turned four. And what I remember most was my mother, panicking. She was panicking. And I remember the house we lived in, right in the middle was a potbelly stove. She burnt anything that had anything to do with Japanese like books; records, record like phonograph record; pictures, any of that, she burnt. Because what was happening was a lot of her friends were being picked up.

Individually right?

Individually. She’d say Mr. So-and-so got picked up or so-and-so got picked up, you know. And panicking. And for good reason. Because my father, before he came to U.S., he was in the Japanese navy.

Oh, okay. They’d have a target on him.

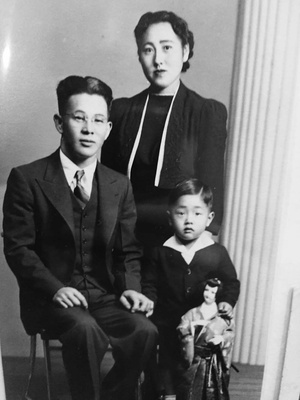

Yeah, he was in the Japanese navy. And he changed his name. So Yamamoto isn’t my real name. It’s Tanaguchi. Essentially, as far as I could figure out, he was an illegal. Which was very common especially with the Chinese. Well, changing the names anyway is very common. Yamamoto was his aunt I think, who lived here in the United States. My mother was surprised as to why wasn’t he picked up, if anything.

He just flew under the radar.

He should have been one of them to go to Crystal City. But those that were sent to Crystal City were people who were in some organization. It may have been as innocent as shigin (Japanese poetry) group and all that which the FBI deemed as being dangerous organizations. And at that time because the Japanese were pretty much isolated, somewhat. And a lot of it self-isolation, by the way. They formed little clubs and so forth. And I think that’s part of the reason, just, they deemed certain organizations or certain clubs as dangerous or subversive.

I was surprised to see pictures of the people in Tule Lake. But there was a radical group and they were exercising. But they were in a line, military line, with the hachimaki.

My dad and Bob [Kaneko] remember being taught by the Kibei who were teaching them the same military style.

So in essence you did have some radicals in there. I remember when I was in high school and you say, “Where did you go [to camp]?” Tule Lake. “Ooooh.” But I don’t know much about Tule Lake. I don’t know much about camp, for that matter.

Well on the flip side, a lot of people have no idea Keetley farms existed and that there were people who were able to avoid internment.

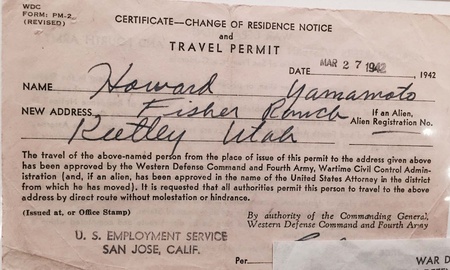

Well, let me show you. Here’s a picture of my travel permit, to get out of California:

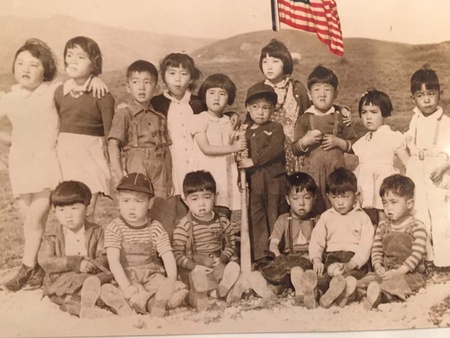

And this is a picture of us young kids at Keetley:

That’s amazing. These were all the kids then?

No, you had high school kids. I don’t know why this group was taken.

And where are you?

Where am I? Oh. The sweet little innocent child here. [laughs] And why this particular group they took I have no idea. Well I know here, none of us, except maybe four or five of were in school.

I do not understand, or, do not know why Mr. Wada took it upon himself to seek a place where he could essentially move his family. Because I don’t think this order to voluntarily evacuate came up yet. I mean he went out way before that, just to look around. From what I understand he went to different areas like Nevada, a lot of places in Utah and such. And boom, denied.

They wouldn’t take a resettlement community?

They just didn’t want the Japanese. But when the word got out among the Japanese, that in fact he was out looking for a place to resettle, first his relatives, distant relatives or whatever, wanted to jump. “You should take us.” And then word got out further. “Would you take us? Would you take us?”

He found a place in Keetley. And then he came back and his plan was to farm in Keetley. But who do you choose to go out? So he picked them by occupations. Especially farmers. Now my father was picked—well first they were good friends, good buddies. But he was initially picked because he was a carpenter. So as a carpenter there’s some use to the colony.

And how did they meet? How were they good friends?

Wada was a big time produce man. He was pretty wealthy. And anyway, my dad worked for him for a while. And they come from the same prefecture, Okayama. So that’s how he got on. Wada himself has eighth grade education, that’s it. When he undertook this voluntary evacuation, he was only 35. How old are you?

30.

Can you imagine doing it?

Nope, not at all.

Yeah. His English is broken, broken English. And then having to go in front of city council to plead with them to please let us in. Quite an undertaking, quite an undertaking, it took a lot of guts. And how he did it? I don’t know.

He had to go in front of the city council in Heber, which is right next to Keetley and convince the people to let us in. The owner of this place, the ranch, George Fisher. They became real good friends and I guess Fisher and Fred got in front of the city council and really had to fight to get the city council to approve.

Fisher had something like 3,000 acres. What it was, was an abandoned mining town. So he wanted Wada to come in but they had to really, really work their tails off just to convince them. Wada even had a talk with the governor of Utah, Maw. Somehow I think Maw got a hold of Fisher and they negotiated. Fred, I remember, in his later years, talked very highly of Fisher, he liked him.

I would think part of the reason the people in Heber gave in was their religion, Mormon. Because the Mormons were under a lot of persecution. So I think they would understand.

How would you describe Mr. Wada’s personality?

He was very self-confident. Just a very self-confident person. Wasn’t among the Japanese, from what I understand, the most popular.

Really. He just rubbed people the wrong way?

In the Japanese group, you don’t stand out, stay within the confines. I mean, that guy stood out. I remember when Mr. Wada attended my dad’s funeral. And we spent some time at my mom’s house. And he looked at me, he says, “Howard.” He’s pretty gruff, but I love him. He says, “Goddamn Habo, [his nickname] you wasted your life being a goddamn teacher. I could have made you into successful business man.” [laughs] And I say, “Oh, okay! Why didn’t you tell me that?”

Glad I know now!

Yeah, he had a really, very strong, strong personality.

Well for someone like that, the prospect of being in prison is enough to make you want to get a group of people to try and beg for your freedom. I understand that.

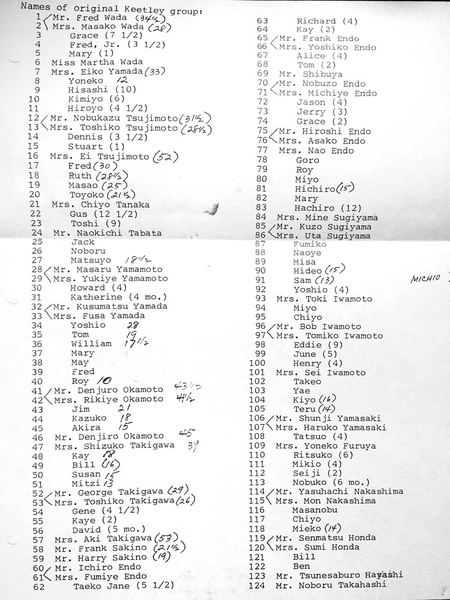

Yeah. This is the list of people who went to Keetley:

Well I imagine very convincing for people to follow him.

Yeah, pick those people and a lot of them, I imagine half of them were somewhat related to him.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on September 30, 2016.

© 2016 Emiko Tsuchida