And underneath this sheltering bowl

We call the sky,

Do not lift up your finger;

For It moves as impotently as you or I.—Omar Khayyam (1048-1131), Persian poet and astronomer

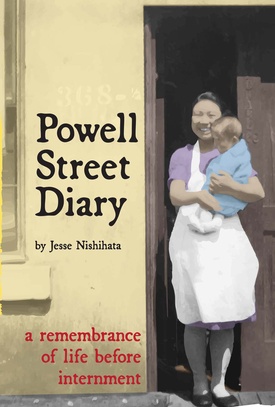

At the 41st Powell Street Festival on August 5 & 6, 2017 in Vancouver, Junji Nishihata will be launching his father Jesse’s book Powell Street Diary: A Remembrance of Life Before Internment posthumously, in his Dad’s pre-WW2 childhood neighborhood, on this, the 75th anniversary of internment.

Junji has been working hard to make this book project come together for many years and, finally, pulled it together in the last few months and is self publishing it.

Jesse’s account of life in the pre-World War Two Powell Street area is the most important book by a Nisei in many years as it fills in so many blanks about what life was like in Japantown/Nihonmachi of Vancouver for a young kid shortly before our mass incarceration for the duration of the war.

I have had the honour to talk to many Nisei oldtimers who grew up in the Powell Street neighborhood, including Jesse. I’ve often wondered about what life was really like for them way back then? Now that those kids are now mostly octogenarians, memories are becoming ‘sketchy’….

Today, I wonder….. were the Asahi ball players really that good? What was it like to walk around an area where there were sento community baths, the dojos, Maikawa shoten, bustling restaurants, the omnipresent wafting aroma of shoyu and fish, the lively banter of Japanese and English and odd mixes of the two everywhere, the ‘secret’ gambling dens (that everybody knew about anyway), the rooming houses, fish markets, the pharmacy, mechanics, the confusing mix of English and kanji signs to signify place, our place, that made up a thriving alien community that was little understood by our ‘hakujin’ neighbours. The active Buddhist temple, Christian churches were there too and so was the Alexander Street Japanese language school were the foundations of that ‘proper’ Canadian community that our upstanding Issei and Nisei wanted desperately to be members of. Hearing the echoing cries of Japanese names across Powell Street: the Japanese names “Tanaka sensei!” “Miyasaki, Oji-san!” “Michiko (Ishii)-san!”; from open doors of shops and homes, hearing loud “tadaima!”, “irasshaimase!,” and “konnichiwa!” add to the chorus of that symphony of sounds that were ours.

Today, Junji lives in Montreal, where Jesse was “relocated” with his own family after WW2, with his wife Akiko and kids: Shu,10, Koko, 8, Gen, 2. His siblings are Alexis, Akira, Masashi, and Emmy. Jesse’s siblings: Miyo, Shoji, and Sumi. Only Shoji is alive at 84 years old.

Powell Street Diary is a feat of extraordinary storytelling by a master storyteller that reminds us of a better time and place.

* * * * *

First, Junji, thanks for taking part in this interview. For those who may not know who Jesse was, can you please give us a bit of a profile of him that might relate to the Powell Street Diary (PSD)?

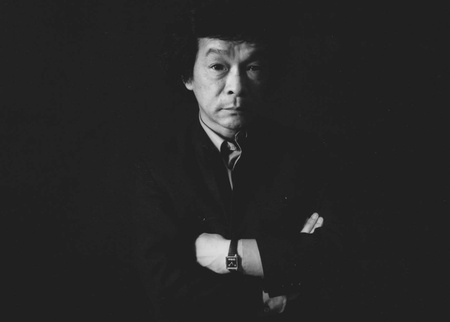

Junji Nishihata: Jesse (born Hideo Nishihata, 1929-2006) was born on Powell Street, in Vancouver’s Japantown, and he lived there until the ‘evacuation’ of Japanese Canadians in 1942. Many years later, he became a documentary filmmaker, and eventually produced Watari Dori, which aired on national TV in 1973. Until that time, the injustice of the internment experience was a topic completely ignored by mass media. It’s probably going too far to say it was a decisive moment in the battle for redress, but I am sure it played a big part in making the subject known to a larger audience. His later films often focused on native issues, as well as other minority groups. This was his career, really, giving a voice to people who didn’t have one, and I think this viewpoint was forged in his days on Powell Street.

For those Nikkei who may not know the importance of pre-World War Two Powell Street in our Japanese Canadian (JC) history can you please contextualize this for us?

Junji: Powell Street was the centre of Japantown in Vancouver, and thus by extension, was the centre of the Japanese Canadian identity. It was the street where all successful Japanese businesses thrived, where the community interacted and where people went to be seen. Later on, as the community went through a kind of rebirth following redress, it once again became the focus of the JC identity, although by this time, the original spirit of the place had changed. Nevertheless, it remains the sentimental heart of the JC story. I recommend those curious to know more should seek out the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, which would be the best resource for all things Powell Street (that and the Powell Street Festival Society).

When you were growing up in Montreal, Quebec, what did Jesse tell you about his childhood on Powell Street? Were there stories he would tell you and your family?

Junji: Actually, no. Like many people of his Nisei generation, he spoke little about the experience. We grew up understanding it, but only in an indirect way. That’s why the book was such a revelation. The extent of detail in it showed me how much it meant to him, and perhaps writing about it was the only way for him to communicate it in a meaningful way.

Why did it take so long to get PSD into print? Did Jesse try to do this in his lifetime?

Junji: The book was published previously in a scholarly journal called Pan Japan. My father being so modest, he probably considered this to be sufficient, and never pursued publishing it elsewhere. I’m not sure when I first got the inspiration to do so, but upon first reading it, I really felt that it needed wider distribution than it received the first time around. Initially, I was focused on professional publication, but that process resulted in a dead end when the first publisher I found asked for rewrites; I wanted to keep the book intact. I then decided to publish independently.

Without telling us too much, can you give us a ‘teaser’?

Junji: The diary is as much about a boy growing up, as it is about what it meant to be Japanese Canadian. It delves into the minutiae of the day—how to play marbles, for example, and how kids amused themselves before the internet existed, or even (gasp) television. But it’s also about the conflict between being ‘Japanese’ and being ‘Canadian,’ and about how difficult it can be to reconcile these identities, especially when the two nations are at war. In the end, we can see that Hideo simply wants to know why: why is he here, what does his life mean? In this sense, I feel the book is rather timeless, even though it evokes a bygone age in rich detail.

For you personally, what importance if any does Powell Street hold for you today especially as you are now a Montrealer?

Junji: To be honest, not so much. I recall for Homecoming in 1990, my father and his brother and two sisters went back to the very storefront where they grew up on Powell Street, a moment that made it onto the evening TV news. It was touching to see their excitement at recalling their memories, and as this was after Redress, there was a feeling of a kind moral retribution. But we never visited as children, and I cannot claim to have a special feeling for the area. Instead, since my grandparents eventually settled in Montreal, and we visited them here, I have more of a sentimental feeling for this city (Montreal) where I now live. I even live on the same street that they did for 30 years!

Can you put his importance as a Nisei filmmaker and artist into the context of today?

Junji: I’m not involved enough in the industry today to be able to comment; I don’t think that his films are being studied today, and I am sure for most contemporary audiences, they would seem horribly dated. But I think that the 1960s and 70s were a great time for documentary film, and he was very much in the thick of it, producing works that were challenging for the content as well as for their technique. For example, he produced The Inquiry Film in 1977, which was made without any voice-over narration—a staple of documentaries then and now. He let the subjects tell the story, and it was a most effective way of letting the audience judge for themselves. It was an approach that earned him the Canadian Filmmakers’ Award that year—the highest accolade in Canada.

How do you want “Powell Street” as it was in the days before internment to be remembered by your own kids? Do you talk to them about Jesse?

Junji: I definitely talk to them about Jesse, and I will do so even more as they get older. I think the works is important not so much for how it recalls a particular time or place, but rather a feeling of indecision, uncertainty and fear that is on the one hand common to all pre-teen and teenage kids trying to find their place in the world, and on the other hand unique to this Japanese Canadian boy who had the misfortune to grow up at a time of war. Jesse’s voice is, and was, absolutely singular, and we can feel it through this piece.

Why might it be important for Nikkei to read this work in 2017?

Junji: I think it is important because it makes the whole experience easy to relate to. It is filled with details and impressions that bring the era to life; instead of just looking at old photos, we can get a sense of who those people, what they said, how they moved, what was important to them. And in so doing, it throws some light on the past, in place of what were often shadows or assumptions we had about who our parents or grandparents were. And at the end of the book, he asks a question that is at the heart of his identity, a question he cannot answer, but one that might resonate with a lot of Nikkei readers. I won’t spoil it, but what he does is personalize and humanize the internment.

Any final words about PSD?

Junji: I just hope this book finds its audience; I am sure it will touch many readers, and not just Nikkei ones. I think it has the ability to cross those boundaries and offer something meaningful to a huge number of people.

* The Powell Street Diary: A Remembrance of Life Before Internment is currently available on Lulu.com and Amazon.ca.

© 2017 Norm Masaji Ibuki