“I remember the regulations being posted on Edison Company poles.”

“And this was the only notification you had--the public posters?"

“Yes.”

“When you got to Poston, what did you think of it?”

“I had a real deep sinking feeling when we saw the place.”~ Hitoshi Nitta, February 7, 1966.

Born in Santa Ana, California, in 1917.

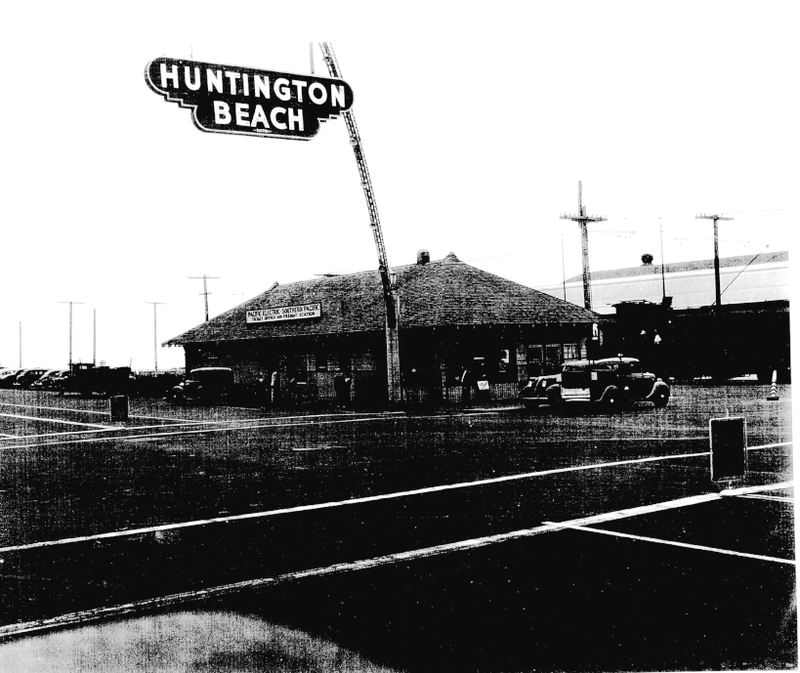

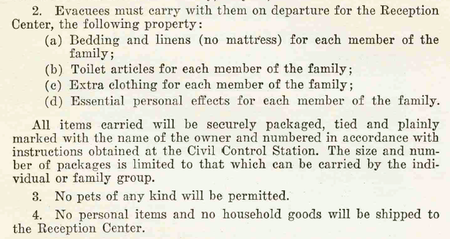

In Orange County, “moving day” was seventy-five years ago: Sunday, May 17, 1942. All persons with Japanese ancestry--including U.S.-born citizens--were instructed to report to various Civil Control Stations or designated departure sites around the County by that date. In Huntington Beach, the departure site was the Pacific Electric Railway station at the foot of the Huntington Beach pier.

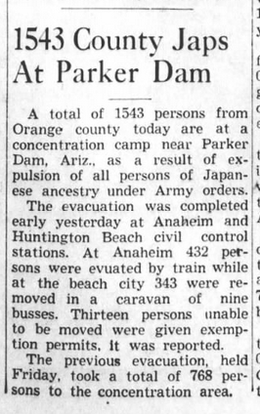

On May 18, 1942, the Santa Ana Register reported a total of 1,543 from Orange County were now at “a concentration camp near Parker Dam, Arizona, as a result of expulsion of all persons of Japanese ancestry under Army orders.”

“We left from the Huntington Beach Pacific Electric station, but we left on a bus. It was a PE bus,” recalled Henry Kanegae in his 1966 oral history with Richard Curtiss for California State College, Fullerton. He and his family farmed about 45 acres near Talbert (Fountain Valley).

Kanegae was 25 at the time he left for the Colorado River Relocation Center (Poston), in Arizona. His wife, two small daughters, and his parents, were part of the Kanegae family group that gathered in Huntington Beach, before their journey to Arizona. He told his interviewer in 1966 that his children “wouldn’t eat or sleep the first two or three days” when they got to Poston. He found baby food at a small market in the camp and made soup with it so his daughters would be comforted and sleep.

Kanegae was interviewed again--at age 75 in 1992--by Dean Takahashi with the Los Angeles Times (“Half a Century Later, Relocation Pain Persists”, February 16, 1992). Then retired from farming and living in Santa Ana, Kanegae vividly remembered the blowing sand of Poston “hit like it was coming from a fire hose, making all kinds of noise. All we saw was dust.”

Kanegae’s interviewer in 1966 asked if the federal government provided them with food or supplies for the journey on the day they left Orange County. Since no one knew for certain where they were going, it was hard to know how long their journey might take. Kanegae did not recall provisions for food for his bus during what turned out to be a minimum nine-hour journey, but remembered a group of women who showed up at the Pacific Electric station in Huntington Beach.

“No, the government did not (provide food), but there was a group of--I believe they were Baptist--ladies who were from the western portion of the county that had coffee and donuts for us,” recalled Kanegae, born in the peatlands of present-day Fountain Valley and a lifelong resident of Orange County. “And after I arrived at camp, I wrote them a letter thanking them for it.”

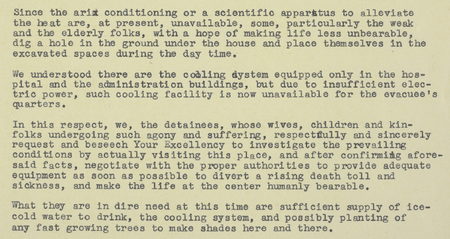

The temperatures in Orange County were rising in mid May, the Santa Ana Register reporting on “mid-summer heat” of 88 degrees by noon. The buses leaving for Arizona had no air conditioning and it got hotter as the day progressed. The barracks that would be their living quarters in Arizona had no cooling systems, the dark tar paper walls only absorbing more heat. As people arrived in the Sonoron desert--where average heat in May is in the mid to high 90 degrees--the temperatures were well above 100 degrees.

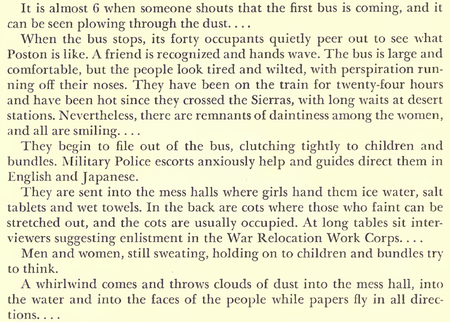

After the day-long journey, some fainted from the heat, lack of water and food, and pure exhaustion. Volunteers handed out salt tablets, ice, and wet towels. The Spoilage notes, “at long tables sit interviewers suggesting enlistment in the War Relocation Work Corps. Men and women, still sweating, holding onto children and bundles try to think.”

A Poston project director is reported as saying, “he thought the people looked lost. He once found a woman standing, holding her 4-day-old baby and sent her to rest in his room.” An associate project director recalled seeing “an elderly mother who had been in a hospital some years propped on her baggage gasping and being fanned by two daughters, while her son went around trying to get a bed set up for her. The old lady later died.”

Upon arrival at Poston-- as well as the other camps--each adult was required to answer questions about their occupation, in order to fill camp jobs. Then, fingerprinting. Then off to another barrack to stand in line for a housing assignment. Then, registration, again, and a physical examination. Only after all this, were families loaded into trucks and driven to their barrack to take stock of their new “home”.

The space allotted to each family in a barrack was a 20 by 25-foot barren room, dust blowing inside through the knotholes and growing cracks of the green lumber drying rapidly in the desert heat. The four family “apartments” in each barrack would be divided by hanging cloth partitions.

For each person, there was one Army cot, one blanket, and one piece of cloth for a mattress. That meant one more task at the end of a never-ending day: find a pile of straw left by the camp administration and fill the mattress cloth, or, go without a mattress that night. And, only then, try to sleep. Listening to the collective silence. Wondering why they were there.

MOVING DAY, MARCH 23 - AUGUST 11, 2017

In conjunction with the exhibition Instructions to All Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066, the Japanese American National Museum presents Moving Day, an outdoor public art installation in Little Tokyo in downtown Los Angeles. The work consists of a series of projections of the Civilian Exclusion Orders that were publicly posted during World War II to inform persons of Japanese ancestry of their impending forced removal and incarceration, a series of dialogues and events grappling with the legacy of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. Learn more here.

*This article was originally published on Historic Wintersburg blog on May 17, 2017.

© 2017 Mary Urashima