Okay, I see. So then you landed in the Philippines.

Yeah. When we were in the Philippines, maybe about two or three weeks later, the war with Japan ended. So the very next day, myself and another desk sergeant who I knew, both of us were flown to Tokyo to the Major Willoughby’s headquarters, to translate newspapers.

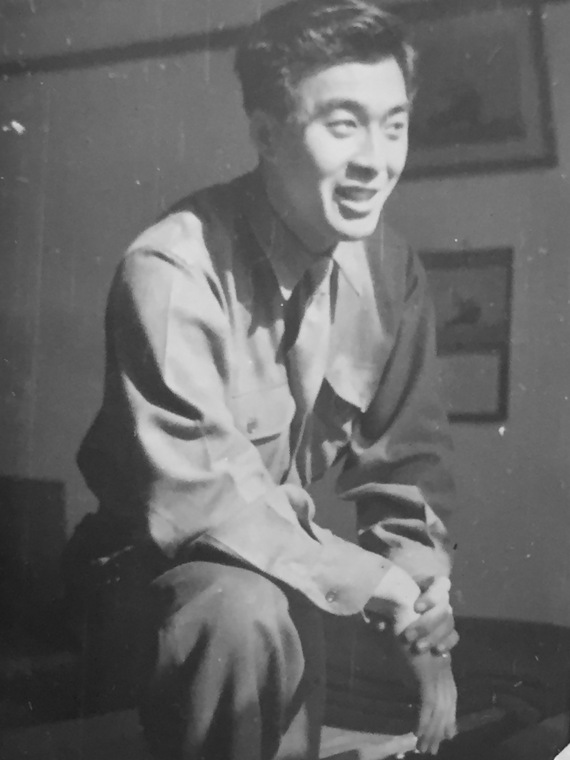

And that’s another part that, when I got to Tokyo and was stationed at the Dai-Ichi building, I noticed there was a police station nearby and I knew my sister was quite famous as a singer, and she escaped during the war there, so I went to the station and asked if she could locate Fumiko Betty Inada and told them that I was working at the Dai-Ichi building. And the very next day a guy comes up and says, “Hey, you got a visitor downstairs.” And I go down there and there she was with Dick Mine. She had been singing with Dick Mine’s band all through her career. I guess since she was well-known, they located her right away.

When was the last time you saw each other?

The last time I saw her was before she went to Japan. And like I say, because of our age difference, I don’t know too much about her or anything. My sister, two years older than myself, she was the closest to her.

So Fumiko, she was okay during the war?

She was safe. She used to say that she got so used to the air raid siren when the planes came over, she liked to bake and stuff, so she got to the point where she wouldn’t go into the shelter, she’d just draw the curtain down so that no lights would show. And then got the point where she didn’t care.

It was just happening so much. So she came to the building where you were working and then?

So she says, well, whenever you are off duty and have free time, come to her place. So, got to the point where a bunch of us from Sacramento would go to Betty’s apartment in the evenings.

And so what was your day-to-day in Tokyo, and what were you doing for work?

For work, we worked at first duty was there at Willoughby’s headquarters, and then after you finished there, they had us with the ATIS, Allied Translator Interpreter Group or Section, where all the translators would go and work and translate documents or whatever they had, just to kill time. And then if you got assigned to certain places, you’d go out. The only assignment I had got while I was there was to the First Cavalry Division, Hiratsuka, they needed an interpreter, and that’s where I went. But meanwhile, before being sent, I was translating medical documents or something like that every day. So I learned all about encephalitis. [laughs]

And why did the U.S. government want those translated?

I don’t know what use those medical things were. Just to keep us occupied I guess. All these [American] officers, they were looking for Japanese swords as souvenirs, they’d just ride around in the jeep and go to police stations where they kept those swords. So as far as the translating, I mean interpreting, it was okay, but we didn’t have translating or anything to do.

They just needed you guys to be there so there was an allied presence.

Yes, in case there was officers wanted us to interpret something or other.

So you’re fluent in reading and writing in Japanese?

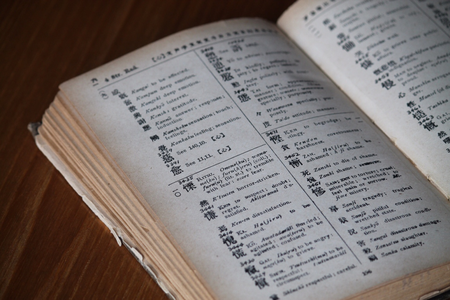

I could recognize Japanese characters, I mean Kanjis and stuff, some of them. But we had a Japanese Kanji Dictionary which I kept when I got out of the army. I still have it. So you could find a character that you don’t know how to read, there’s a way of looking at it and it gives you the meaning and all that. I referred to that quite often.

So would you say most of you in the MIS were pretty much the same level? In reference to being able to translate and all that?

No.

Some were pretty fluent?

Most of them at the time that I went to MIS were pretty close. Not that close and not that great. But the earlier ones, especially the Kibeis, they were the good ones.

So, you know, when I think about it, I belonged to MIS but, didn’t see any action or anything like that. I just don’t feel like you did much of anything.

Do you feel somewhat lucky though, because of how many casualties there were in the 442?

Yeah. That’s the reason I’ve always just gotta think to myself, I don’t know what it is but everything happens to me by chance or coincidence. And I get spared.

So you were in Japan for how long?

I wrote Yoshiko that I would take a civil service job for a year to spend time with [my sister] and get to know her. So I took my army discharge and then I worked for the federal government in civil service and got a job with the Stars and Stripes army newspaper in the art department. So that was when my year contract with the government was up in a year, I told my officer, he had also been an officer and he had taken a civil service job and he was the editor. He was the head man. I said, my contract is up so I’ll go back to the States. He said, “Oh, you’re stupid, you can’t find a job like this back home now.” “I’ve got a girl waiting for me. That’s the reason why I’m going home.” [laughs]

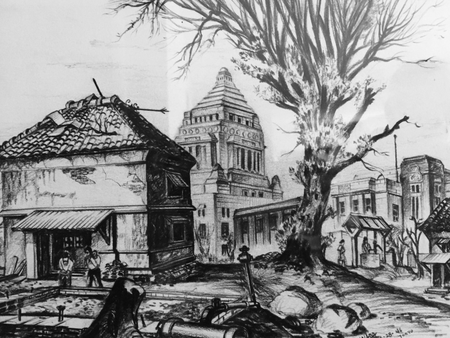

Priorities! Were you shocked at seeing the destruction of the city?

Yeah, ’cause other than parts that were spared, everything was burned down.

Did you talk to civilians that either were curious about Americans or did you not interact too much?

No. After I took a civil service job, like our people after we became civil service workers, we didn’t pay much attention to the Japanese living there. You just occupy yourself, like judo and stuff like that.

You were kind of in a bubble.

Yeah.

And were you keeping in touch with your family?

They had gone back to Sacramento. My father wanted to go back to Japan from Tule Lake but the rest of the family said no they’re not going back. So they moved to Granada, Colorado and in fact, they were already there and when I was going to go overseas, we were allowed to go visit them. My father changed his mind and he was able to go to Granada. Then my youngest sister, and my father and mother went back to Sacramento. And my father bought into a partnership with a family and started a soda fountain business, or snack shop.

And the house was taken care of?

The house was still there.

That’s very rare. I’ve usually heard that people’s property wasn’t kept.

Yeah, I guess it was a deputy sheriff. I guess he kept his word.

And so did you work at the shop?

No, I was still in Japan. So when my contract was over, I came back and I must’ve stayed about a month or so in Sacramento and then I told my parents I was going to get married in Chicago. So we had a wedding, my father and my sister who was in New York came to the wedding.

You said you got engaged through your letters. Was there something that made you want to ask her, or did you just know from the very beginning?

Yeah, I think so. Because I was pretty faithful.

How did you end up back in California after Chicago?

My son David was born in Chicago, and when he was about 5 years old, we decided we’d go back to California. So we drove back in a 1956 Chevrolet, I think I had. We drove cross country and went by way of Santa Maria. Yoshiko’s father had been the minister at the Methodist Church there from before the war, so he had been there for 25 years. So Yoshiko, David and myself drove there on the way back, first time I met my father-in-law. I think my wife told me, “My father says you’re too quiet.” [laughs]

And did you have any other children?

I had another son, Rick. And now I have four great-grandchildren. People ask me what is my greatest accomplishment in life, and I say my family.

*A special thank you to Howard Yamamoto for coordinating this interview.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on February 10, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida